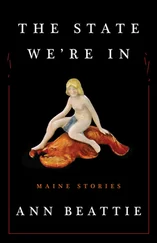

Ann Beattie - The New Yorker Stories

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Ann Beattie - The New Yorker Stories» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Жанр: Старинная литература, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:The New Yorker Stories

- Автор:

- Жанр:

- Год:неизвестен

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:5 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

The New Yorker Stories: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «The New Yorker Stories»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

The New Yorker Stories — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «The New Yorker Stories», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

What did they plan to do? Have the baby and live in the house?

Francis had climbed to the second floor, where his wife had packed his aunt’s clothes into boxes to be donated to charity. There was toile de Jouy wallpaper in his aunt’s bedroom. Near the end, his aunt, on high doses of painkiller, had thought she was stretched on a divan surrounded by a party of French aristocrats, the women dressed in feathery bonnets and carrying parasols, the men on horseback, all awaiting her cue to open celebratory bottles of champagne. Aristocrats, in a nine-by-twelve bedroom on the second floor of a house in rural Maine. Who knew what she’d made of them all being pastel blue? Perhaps that they were cold.

His aunt had died of pancreatic cancer less than two months after she was given the diagnosis. When she called them with the bad news, he and Bern had driven out to the house and cried and cried, unable to think of anything optimistic to say. His aunt had pressed jewelry on his wife, though Bern was a no-nonsense sort of woman who usually wore nothing but her wedding ring and a Timex. His aunt had told them her sensible plan for what she called “home help.” She had asked him, as a complete non sequitur, to change the light bulbs in the hallway, but instead of doing this immediately they had talked more—Bern, in her strong way, had been very upset. And then he had left that night, forgetting to do the one little thing his aunt had asked of him. He had not remembered until almost the day she died.

There was a faint odor of ammonia in every room, and he thought that might be what he’d been squinting against. Bern had opened all the blinds; it made the house look more spacious, the real-estate agent had told her. So where had his aunt’s spirit gone, he wondered; had it lingered for a moment in the pastel confusion, then permeated the window—nicely beveled old glass—to alight briefly in the now smashed tree? If so, she’d had a safe landing, leaving well before the moving van pulled in.

Francis never knew what was the proper amount to tip moving men. It had probably become more than he could imagine, if the average tip in a nice restaurant was at least twenty percent, no matter how indifferent the service. He wondered if his seeing the decoys meant that he must buy one; if so, what would they cost, and shouldn’t he tip the men before he got to Jim’s workroom, because otherwise the price of purchase might be confused with the tip. Or, if he tipped generously in advance (whatever generously meant), might the decoy have a more reasonable price?

He backed the Lexus out to follow the moving truck down the drive. Jim drove faster than Francis expected, but he kept up, patting his pocket to make sure that his cell phone was there. They drove for a while, then turned down a rutted road where someone had put a red-and-black cone to indicate a deep pothole. The houses here were smaller than the ones on the main road. With all that he had to do, what was he doing going into the woods with two men to see decoys? It was the sort of thing that could turn out badly, though his instincts told him it would not. Still, he could imagine being in court, asking the defendant with a hint of skepticism in his voice, “You followed these two strangers to one of their houses?”

When the road forked, the truck slowed and Jim put down his window, pointing to the right with his thumb. Francis hesitated. The truck continued to the left, bumping onto a field. He thought he understood and took the right fork, stopping in front of a little clapboard house that stood alone, with no trees in front and only a half-dead bush in the side yard. It was, indeed, very small. Again he heard himself in the courtroom: “And with no hesitation you got out of your car?”

He got out. Don and Jim were walking toward him. He could tell from their faces that there was nothing to fear. Don was holding a can of seltzer. Jim—who looked much larger beside his tiny house—had a set of keys in his hand, though he used none of them to open the unlocked door.

“Used to live in a Victorian over in Milo,” Jim said. “Wife comes home one day, says she’s seen to it I can’t come within ten feet of her. For nothing! Never laid a hand on a woman in my life. You can march into the police station, if you’re a woman, and just get an order to have a guy gone from your personal space, like it hadn’t been his space, too.”

“Bitch,” Don said, under his breath.

“Do you have children?” Francis asked.

“Children?” Jim said, somewhat puzzled. “Yeah, we had a kid that had a lot of problems that we couldn’t take care of at home. One of those things,” he said.

Don averted his eyes and toed a dandelion that had gone to seed.

“I’m sorry,” Francis said.

Don said, “I got one wife, no kids, a bulldog, and half my life stacked up in some storage place by her brother’s, since we had to downsize when the balloon came due. Downsized into my brother-in-law’s garage! You know what I mean?”

He did, actually. “Yes,” he said.

Jim tossed the big key ring on the worktable, which took up most of the room. There was a single bed pushed in the corner with a cat lying on it that looked something like Simple Man. The cat raised its head, then curled onto its side to continue its nap. There was a brown refrigerator in the corner opposite the bed, and a sink hung on the wall. The toilet sat next to the sink. He saw no sign of a shower.

“Sit,” Don said, pulling out a canvas director’s chair. Francis counted seven such chairs, most of them similar to the first, but avoided the one that sagged badly.

“Could you use a beer?” Jim said.

“That would be nice,” Francis said. He told himself, I can’t call my wife, because how would I explain where I am? He reached for the can of Coors, which was icy cold. He could not think of the last time he’d had a beer, rather than a Scotch-on-the-rocks. He raised the can, as they all did, in silent toast to whatever they were toasting.

It did not look as though Jim had done any work on the table recently. There were piles of newspapers, dishes, something that looked like part of a saddle. In a glass, there were some feathers. Francis wished that he could see some wood chips. The table looked too low to carve on—you would stand to carve, wouldn’t you? He saw with relief that there were a few tools, but the one he focused on looked rusty. “O.K., let me get ’em out,” Jim said, kneeling.

He lifted a box from under the table, opened the lid, and unwrapped a white towel inside. The box itself was beautifully made, with the word “Mallard” burned into the wood on the underside of the lid. Jim removed a duck and put it on the table.

“Un-fucking-believable,” Don said, shaking his head.

Jim took a step back, cleared his throat, and said, rather formally, “Some would do it different, but I use black eyes on the mallards. Ten millimeter,” he added. Francis stood with his can of beer, looking down. He wondered if he was supposed to touch it. It was quite convincing, and really beautiful. He moved forward tentatively, and, as he did, Don said, “Let me get that Coors outta your way,” sweeping the can out of Francis’s hand.

Francis held the decoy at a distance where he could see it clearly without putting on his reading glasses. Jim was pulling out other boxes. “Got one more to go, then I ship ’em off. Guy from Austin, Texas. He got himself an art gallery as a ‘ship to’ address, so maybe it doesn’t matter if he’s got no real idea what he’s doing,” Jim said. “Guy wants nothing but mallards, O.K., but if you’re going to set out decoys, then, yeah, you can have mallard, mallard, mallard, mallard—lots of ’em. But you throw in one of these—” He set another box on the table, and unwrapped a beach towel. “This is your egret. You put all the mallards out there, but if you’re going hunting you need something like this egret, for a confidence decoy.”

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «The New Yorker Stories»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «The New Yorker Stories» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «The New Yorker Stories» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.

![О Генри - Рождение ньюйоркца [The Making of a New Yorker]](/books/405345/o-genri-rozhdenie-nyujorkca-the-making-of-a-new-yo-thumb.webp)