“And this. . . velociraptor was like a bird that way?”

“Sure. They both have three primary toes on their hind feet. And necks that curve into an S shape. And, see here,” he said, pointing, “velociraptor has long arms, and a wrist bone like a bird’s wing. There’s other common characteristics too: like how nerves travel from the brain, the air spaces in the skull, and the construction of the hips and thighs. It may even have built nests like birds and tended its eggs and all.”

“But not fly?”

“Not in that. . . stage. We don’t know if it disappeared, or just evolved into something else. Like the eohippus into the horse, see?”

“Sure,” I said. The kid was already talking like his father—what I really needed was a translator.

“Look at the skeleton,” he said, pointing again. “From the sizes of the various bones, and the light, delicate structure of the limbs, you can see it was probably a fast, nimble runner. It wasn’t huge or anything, but it was well armed. See this?” he asked, pointing to a large, hook-shaped piece coming out of the toe joint. “They call it a ‘killing claw,’ so it was probably used to hunt other animals, not to dig in the ground or anything. Velociraptors had more than eighty teeth, some of them over an inch long, and each with a sharp, jagged edge. Awesome, huh?”

“Were they. . . I don’t know. . . smart?”

“Probably,” the kid assured me. “The brain was large and complex. That means that they were probably intelligent, with good hearing and eyesight, and even a good sense of smell.”

“So they were like predatory birds—hawks and all—but they worked the ground, right?” I asked him. Thinking how human vultures never have to fly to feed.

“We really don’t know,” the kid said solemnly. “Only one truly great specimen was ever discovered—a fossil. And it shows a velociraptor and a protoceratops locked in deadly combat.”

“But nobody knows who started that one?”

“Or who finished it either. Like a movie where you have to leave before it’s over. But, from all I read, it seems like velociraptor was a great hunter. And a great fighter too. The evidence. . . I mean, what they found. . . it had characteristics of both birds and crocodiles—that’s those rows of teeth and all. And those are both still around—birds and crocodiles, I mean. So I don’t think it died out, the way the bigger ones did—it was too well adapted to its environment. It probably just. . . evolved into something else.”

Was that his message? I thought to myself. That he hadn’t died, just evolved? That he was a perfect predator for the times, and he’d move along once his work was done?

“Which do you think?” I asked the kid.

“What do you mean?”

“Well, you said it had characteristics of both birds and crocodiles, right? So it had to go in one of those directions if it was going to survive.”

“Birds,” the kid said, unhesitatingly.

“Why? Crocs are ancient. I mean, they go all the way back to. . .”

“They both build nests, right? Birds and crocodiles. But only birds take care of their babies when they’re born. When the baby crocs are born, they’re on their own.”

“And you think that’s the key to survival?”

“For the higher life-forms? Sure. It makes sense, right?”

“If it does,” I asked him, “what the fuck are we still doing on this planet?”

The kid—this kid whose bio-parents had sold him like a used car—looked at me for a long moment. Then he said: “We’re not all like. . . that.” And then he glanced toward the bunker where his real parents were being with each other.

I nodded, agreeing. But not believing. The human race is a race. And I’m not sure parents like Michelle and the Mole are winning it.

“Would anyone be likely to recognize this?” I asked the kid, showing him the icon again, working for a smooth transition, moving as far away from the other as I could get.

“Sure, if they knew anything about the subject. Like a paleontologist. But not from the name.”

“Huh?”

“ ‘Velociraptor’ was the name they used in Jurassic Park. You know, the movie? But the ones there were nothing like the real ones. If you said ‘velociraptor’ to the average kid, he’d never think it looked anything like this. ”

I lit another smoke. “You did great, Terry,” I told the kid. Thinking maybe I had something to make that polygraph key really sing, now that I had lyrics to go with the music.

Michelle was quiet on the drive back, and I knew better than to break the silence. She could dissect my sex life for hours without batting an eyelash, and she’d turned every kind of trick there was before she took herself off the streets and went to the phones to make a living, but even mentioning her and the Mole together was total taboo.

Terry was always a safe topic with her—she loved that kid way past her own life—and she would have been proud about how he’d helped me out. But she was so inside herself that I didn’t even tap on the door. Just took her absentminded kiss on the cheek before she slipped out in front of her place and then motored over to Mama’s.

Red-dragon tapestry in the front window. Maybe Lorraine had found Xyla already. Or maybe not. I pulled around the back, flat-handed the metal slab of a door, and waited. One of Mama’s crew opened the door, a guy I hadn’t seen before. I could swear his face was Korean, but I knew how Mama was about things like that, so I kept the thought to myself. He said something over his shoulder and one of the guys who knew me answered him. The new man stepped aside to let me pass, his right hand still in the pocket of his apron. Whatever was out front wasn’t that dangerous, anyway.

It was Xyla. Sitting in my booth, facing toward the back, working her way through a plate of dim sum someone had provided. Good sign. Mama served strangers toxic waste—her real customers never came for the food.

“What’s up?” she greeted me. “Lorraine said you were looking for me.”

“Yeah,” I said, sitting down. “Be with you in a minute.”

It was less than that before the tureen of hot-and-sour soup was placed before me. I filled the small bowl myself, drained it quickly. I glanced toward where Mama was working at her register, but I couldn’t risk it—had two more bowls before I waved at the waiter to take the rest away. I didn’t offer any to Xyla, and she seemed to understand. . . just sat there, chewing delicately on her own food, waiting.

“What kind of name is Xyla?” I said, my tone telling her I really was interested, not putting her down. I wanted to start cutting her out of the herd if I could, form my own relationship, just in case Lorraine’s old hostility flared up and she tried to cut me out first.

“My mom gave it to me,” she said, chuckling. “It comes from ‘Xylocaine.’. . . Mom said if it wasn’t for Xylocaine my old man never could’ve lasted long enough to get her pregnant.”

“Damn! That’s cold.”

“It was a joke,” she said, watching me carefully. “The kind you tell your daughter when she’s old enough to ask where her father is. . . and you don’t know the answer.”

“Ah.”

“Yeah,” she said, dismissing it—an old wound, healed. But it still throbbed when the weather was wrong.

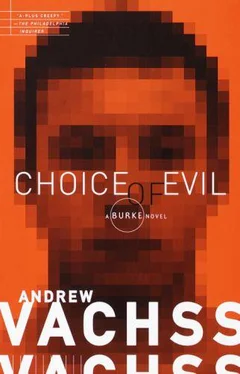

I’d made a mistake. My specialty with women. So I switched subjects as smoothly as I could. “I got the word I want you to use,” I told her. It’s ‘velociraptor.’ Can you—?”

“Like in Jurassic Park ? Sure. How do you spell that?” she asked me, pulling a little notebook from the pocket of her coat.

Читать дальше