A beautiful, slender woman in a plain blue dress. Still in shock, as if they’d just told her last night.

“You work for Giovanni?” she finally asked.

“I’m doing this job for him,” I said, treading carefully.

“You’re not in his...organization?”

“No. I’m not in any organization.”

“You’re not a criminal?”

“No, ma’am, I’m not.”

“Yes, you are,” she said, in a sterilized voice. “Some kind of a criminal. Everyone in Gio’s world is a criminal of some kind.”

I didn’t say anything.

“What did he hire you to do?” she asked.

“To find who...murdered your daughter. And why they did.”

“The police say they know.”

“ What!? They know who—”

“Not who,” she said, emotionless. “Why.”

“Those are guesses, Ms. Greene. Theories. The only sure way to find the person who actually—”

“Why do you say that?”

“Well, theories are generalizations. They’re based on—”

“No. Not that. ‘Person,’ you said. The police said it was a man.”

“I can understand why they might think that, ma’am. And I’m not arguing with it. Just trying not to exclude anyone until I know more.”

“More?”

“More than I know now,” I said, trying to catch her waves so I could surf. “Some of it, I hope you’ll tell me. The rest, I have to find on my own.”

“And Giovanni hired you to do that?”

“Yes, he did.”

“Will you do it yourself?”

“Mostly. It depends on what it turns out is needed. I might bring others into it, if I have to.”

“Needed?”

“To find the person.”

“So Giovanni can kill him,” she said, with no-affect certainty.

“I don’t know anything about—”

“Oh, Gio will kill him,” she said, mournfully confident. “Honor is so very important to him.”

“Honor?” I asked, switching roles.

She smiled faintly, without warmth. “You’re right, of course. I said ‘honor,’ but I meant ‘image.’ What the kids call ‘face.’ That is Giovanni, right there. That sums him up.”

“I don’t know him,” I slip-slided.

“You said it might not be a man.”

“Giovanni, I mean. I don’t know...the child’s father. I’m doing a job of work for him, that’s all.”

“Father?”

“Ma’am, I am truly sorry if I keep stumbling around. I can’t seem to find the right words. I don’t know Giovanni. And I’ll never know your daughter. But if you’ll help me know about her, maybe I can find who killed her.”

“What then?”

“When I find whoever did it... if I can?”

“Yes. What then? Will you tell the police?”

“That’s not my job.”

“Will you tell me?”

“Yes,” I spooled out the lie like a bolt of silk, “of course I will. You have the right to know.”

“Please wait here,” she said. At a nod from me, she stood up and walked out of the room.

Ididn’t move from where I was seated, contenting myself with a visual sweep of the room. It was neat and clean, but without that demented gleam you get under a No People, No Pets, No Playing regime. The room was clearly for company, but not the kind that kicked back with a few beers and watched a football game with their feet on the coffee table.

I’d been in homes where people had lost their child to violence before. I expected at least one photo of the girl—a shrine wouldn’t have surprised me.

Nothing.

When the mother came back, she was carrying a large gray plastic box by the handle. When she opened the top, I could see it was filled front-to-back with file folders. She knelt, placed it on the floor in front of my chair, said, “I have three more,” and walked off again.

I didn’t think about offering to help her any more than I did about looking through the files outside her presence.

“It’s all there,” she said, finally. If lugging all those boxes had tired her, she kept it off her face. Her breathing was as regular as if she’d never left the couch. “The first one is everything that was in the newspapers, and everything I got from the police. The others are all...Vonni. From her baby stuff to just before...”

“I—”

“The reason they’re like that,” she interrupted, “is because of...what happened. I always kept Vonni’s...everything. Every report card, every note from school, every doctor’s visit...I always took pictures, too. But I didn’t have them in this...this filing system, before. I was trying to help the police. They had so many questions, they kept coming back and back and back. Finally, I put this all together for them. But it wasn’t what they were interested in, I guess.”

“They wanted to know about her boyfriends, right?”

“Yes.”

“And yours?”

“Yes.” No reaction, flat.

“Her teachers? School friends?”

“Yes.”

“Her computer?”

“Oh yes.”

“Drugs? Parties? Gangs?”

“Of course,” she said, a tiny vein of sarcasm pulsing in her voice.

“And they drew a blank with all of that?”

“That? There were no drugs. There were no gangs.”

“They said this? Or you just know from your own—?”

“ I said it. They didn’t believe it. They didn’t say so, not out loud. But I could tell. After a...while, after a while, though, they believed it.”

“And they apologized for—?”

“Be serious,” she said.

She didn’t offer me so much as a glass of water. Just sat there watching me go through the files, one at a time. I wanted to start at the latest ones and work backwards, but I could sense that would sever the single frayed thread between us.

I tried to engage her in conversation as I worked. Several times. All I got for my efforts was monosyllables. And when I suggested that I could maybe take the files with me, return them later, I got a look that would have scared a scorpion.

Okay.

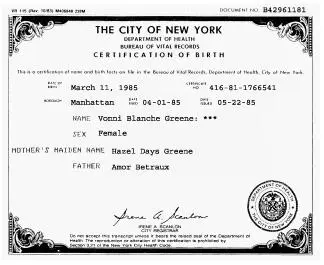

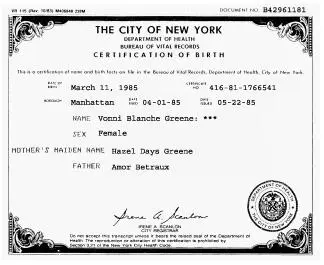

The birth certificate was strangely impersonal.

I’d seen New York birth certificates from the Fifties. They were a lot richer in detail, and a lot less socially correct. They used to give you the time of birth, the number of children “previously born alive” to the mother, the race and occupation of the parents...even where they lived. But I thought that even the little bit of information on this one might open a door, if I could just engage the mother....

“I thought her name would be spelled differently,” I said.

“Vonni’s name?”

“Yes.”

“I don’t understand.”

“I thought it was...a reference to Giovanni.”

“Yes, that’s right. But I spelled it the way it should be pronounced, so her friends wouldn’t get it wrong. Or her teachers, when they called on her in class. Vonni might not have felt comfortable correcting people all the time, just gone along with whatever they called her. When she was little, I mean. I didn’t want that. I mean, if I spelled it like ‘Vanni,’ they’d all think they should say it like ‘Vanna’ with a ‘y.’ Vanny. Then she’d have no connection to her father at all. No child would want that, would they?”

“No,” I assured her, “they wouldn’t.” Thinking of my own birth certificate. The one that said “Baby Boy Burke.” Time of birth: 3:03 a.m. If I ever wanted my first name to link me to my father, I’d have to change it to “Unknown.”

I kept looking. A color photo marked “5/13/91” on the back showed a pretty, slightly chubby little girl, more darkly complected than her mother, with long wavy hair. The child had almond eyes, and a smile you could arc-weld with.

Читать дальше