"We were all ordered by Wad Gamr to gather near his house, and when the signal was given we were to run in and kill the white men. We saw them go up to the house. They had been told to leave their arms behind them; one of the sheik's servants came out and waved his arms, and we ran in and killed them."

"What happened then?"

"We carried the bodies outside the house. Then we took what money was found in their pockets, with watches and other things, in to the sheik, and he paid us a dollar and a half a head, and said that we could have their clothes. For my share I had a jacket belonging to one of them. When I got it home I found that there was a pocket inside, and in it was a book partly written on, and many other bits of paper."

"And what became of that?" Gregory asked eagerly.

" I threw it into a corner, it was of no use to me. But when the white troops came up in the boats and beat us at Kirbekan I came straight home and, seeing the pocket-book, took it and hid it under a rock, for I thought that when the white troops got here they would find it, and that they might then destroy the house and cut down my trees. Then I went away, and did not come back until the}' had all gone."

"And where is the pocket-book now]"

" It may be under the rock where I hid it, my lord. I have never thought of it since; it was rubbish."

"Can you take me to the place?"

"I think so; it was not far from my house. I pushed it

under the first great rock I came to, for I was in haste and wanted to be away before the white soldiers on camels could get here."

"Did you hear of any other things being hidden?"

"No; I think everything was given up. If this thing had been of value I should perhaps have told the sheik, but as it was only written papers and of no use to anyone, I did not trouble to do so."

" Well, let us go at once," Gregory said, rising to his feet. " Although of no use to you, these papers may be of importance."

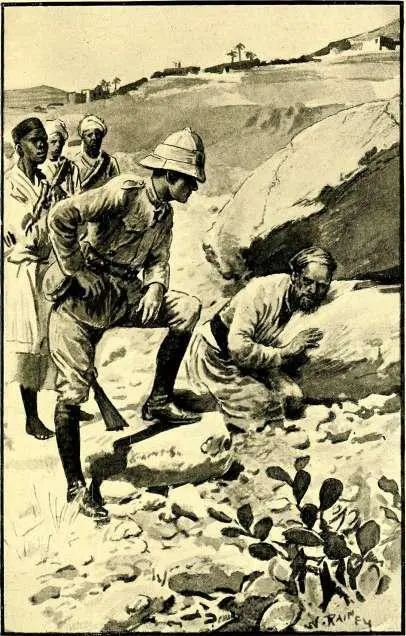

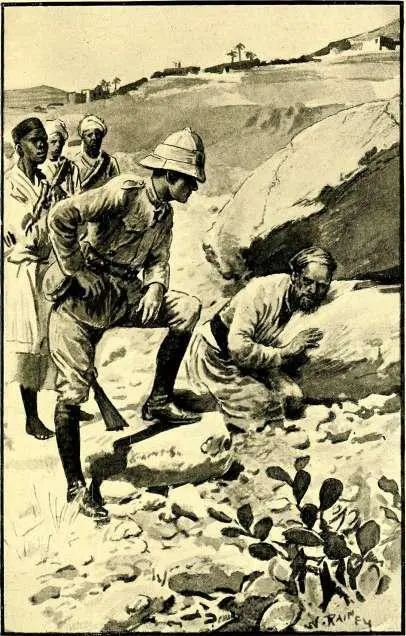

Followed by Zaki and the four men, Gregory went to the peasant's house, which stood a quarter of a mile away.

"This is not the house I lived in then," the man said. " The white troops destroyed every house in the village, but when they had gone I built another on the same spot."

The hill rose steeply behind it. The peasant went on till he stopped at a large boulder. "This was the rock," he said, " where I thrust it under as far as my arm would reach. I pushed it in on the upper side." The man lay down. "It was just about here," he said. "It is here, my lord; I can just feel it, but I cannot get it out. I pushed it in as far as the tips of my fingers could reach it."

" Well, go down and cut a couple of sticks three or four feet long." In ten minutes the man returned with them. "Now take one of them, and when you feel the book push the stick along its side until it is well beyond it. Then you ought to be able to scrape it out. If you cannot do so, we shall have to roll the stone over. It is a big rock, but with two or three poles one ought to be able to turn it over."

After several attempts, however, the man produced the packet. Gregory opened it with trembling hands. It contained, as the man had said, a large number of loose sheets, evidently torn from a pocket-book and all covered with close writing. He opened the book that accompanied them. It was written in ink, and the first few words sufficed to tell him

that his search was over. It began: "Khartoum. Thank God, after two years of suffering and misery since the fatal day at El Obeid, I am once again amongst friends. It is true that I am still in peril, for the position here is desperate. Still, the army that is coming up to our help may be here in time; and even if they should not do so this may be found when they come, and will be given to my dear wife at Cairo if she is still there. Her name is Mrs. Hilliard, and her address will surely be known at the Bank."

"These are the papers I was looking for,"he said to Zaki; " I will tell you about them afterwards."

He handed ten dollars to the native, thrust the packet into his breast-pocket, and walked slowly down to the river. He had never entertained any hope of finding his father, but this evidence of his death gave him a shock. His mother was right, then; she had always insisted there was a possibility that he might have escaped the massacre at El Obeid. He had done so; he had reached Khartoum, he had started full of hope of seeing his wife and child, but had been treacherously massacred here. He would not now read this message from the grave, that must be reserved for some time when he was alone. He knew enough to be able to guess the details—they could not be otherwise than painful. He felt almost glad that his mother was not alive. To him the loss was scarcely a real one. His father had left him when an infant. Although his mother had so often spoken of him he had scarcely been a reality to Gregory, for when he became old enough to comprehend the matter it seemed to him certain that his father must have been killed. He could then hardly understand how his mother could cling to hope. His father had been more a real character to him since he started from Cairo than ever before.

He knew the desert now and its fierce inhabitants. He could picture the battle, and since the fight at Omdurman he had been able to see before him the wild rush on the Egyptian square, the mad confusion, the charge of a handful of white officers, and the one white man going off with the

GREGORY FINDS HIS FATHERS PAPERS

black battalion that held together. If, then, it was a shock to him to know how his father had died, how vastly greater would it have been to his mother! She had pictured him as dying suddenly, fighting to the last and scarce conscious of pain till he received a fatal wound. She had said to Gregory that it was better to think of his father as having died thus than lingering in hopeless slavery like Neufeld; but it would have been agony to her to know that he did suffer for two years, that he had then struggled on through all dangers to Khartoum, and was on his way back full of hope and love for her when he was treacherously murdered.

The village sheik met him as he went down.

"You have found nothing, my lord?"

"Nothing but a few old papers," he said.

"You will report well of us, I hope, to the great English commander?"

" I shall certainly tell him that you did all in your power to aid me."

He walked down towards the river. One of the men who had gone on while he had been speaking to the sheik, ran back to meet him.

"There is a steamer coming up the river, my lord."

" That is fortunate indeed," Gregory exclaimed. " I had intended to sleep here to-night, and to bargain with the sheik for donkeys or camels to take us back. This will save two days."

Two or three native craft were fastened up to the shore waiting for a breeze to set in strong enough to take them up. Gregory at once arranged with one of them to put his party on board the steamer in their boat. In a quarter of an hour the gun-boat approached, and they rowed out to meet her. As she came up Gregory stood up and shouted to them to throw him a rope. This was done, and an officer came to the side.

" I want a passage for myself and five men to Abu Hamed. I am an officer on General Hunter's staff."

"With pleasure. Have you come down from the front?" he asked, as Gregory stepped on board with the five blacks.

"Yes."

"Then you can tell me about the great fight. We heard of it at Dongola, but beyond the fact that we had thrashed the Khalifa and taken Omdurman, we received no particulars. But before you begin, have a drink. It is horribly annoying to me," he went on, as they sat down under the awning, and the steward brought tumblers, soda-water, some whisky, and two lemons. Gregory refused the whisky, but took a lemon with his cold water. "A horrible nuisance," the officer went on. "This is one of Gordon's old steamers; she has broken down twice. Still, I console myself by thinking that even if I had been in time very likely she would not have been taken up. I hope, however, there will be work to do yet. As you see, I have got three of these native craft in tow, and it is as much as I can do to get them up this cataract. Now, please tell me about the battle."

Читать дальше