" I would just as soon be lieutenant, sir, so far as I am concerned myself, but of course I feel honoured at receiving the title. No doubt it would be much more pleasant if I were attached to an Egyptian regiment. I do not know whether it is the proper thing to thank the Sirdar. If it is, I shall be greatly obliged if you will convey my thanks to him."

"I will tell him that you are greatly gratified, Hilliard. I have no doubt you owe it not only to your ride to Metemmeh, but to my report that I did not think Ahmed Bey would have ventured to ride on into Berber had you not been with him, and that you advised him as to the defensive position he took up here, and prepared for a stout defence until the boats could come up to his assistance. He said as much to me."

At the hour named Gregory went on board the Zafir, Zaki accompanying him with his small portmanteau and blanket.

"I see you are punctual, Mr. Hilliard," the commander said cheerily; "a great virtue everywhere, but especially on board ship, where everything goes by clock-work. Eight bells will sound in two minutes, and as they do so my black fellow will come up and announce the meal. It is your breakfast as much as mine, for I have shipped you on the books this morning, and of course you will be rationed. Happily we are not confined to that fare. I knew what it was going to be, and laid in a good stock of stores. Fortunately, we have the advantage over the military that we are not limited as to baggage."

The breakfast was an excellent one. After it was over, Commander Keppel asked Gregory how it was that he had— while still so young—obtained a commission, and expressed much interest when he had heard his story.

" Then you do not intend to remain in the Egyptian army?" he said. " If you have not any fixed career before you, I should have thought that you could not do better. The Sirdar and General Hunter have both taken a great interest in you. It might be necessary perhaps for you to enter the British army and serve for two or three years, so as to get a knowledge of drill and discipline; then from your acquaintance with the languages here you could, of course, get transferred to the Egyptian army, where you would rank as a major at once."

"I have hardly thought of the future yet, sir; but of course I shall have to do so as soon as I am absolutely convinced of my father's death. Really, I have no hope now, but I promised my mother to do everything in my power to ascertain it for a certainty. She placed a packet in my hands, which was not to be opened until I had so satisfied myself. I do not know what it contains, but I believe it relates to my father's family.

" I do not see that that can make any difference to me, for I certainly should not care to go home to see relations to whom my coming might be unwelcome. I should greatly prefer

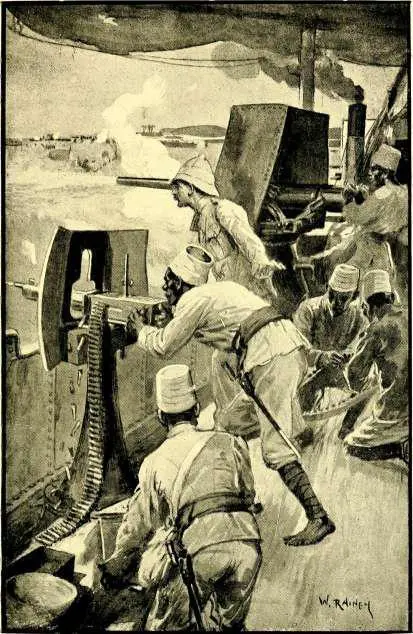

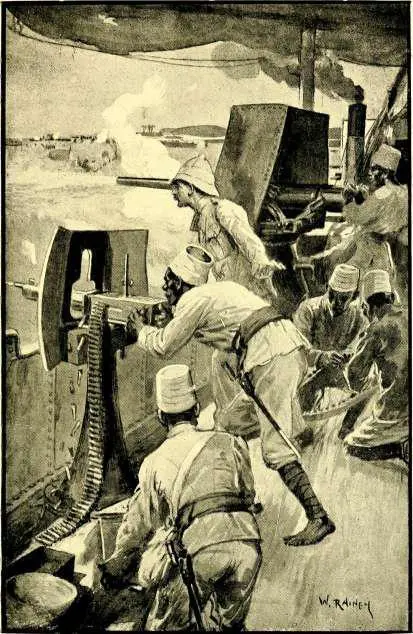

THE GUN-BOATS OPENED FIRE AT THE TWO NEAREST FORTS

to stay out here for a few years until I had obtained such a position as would make me absolutely independent of them."

" I can quite understand that," Captain Keppel said. "Poor relations seldom get a warm welcome, and as you were born in Alexandria they may be altogether unaware of your existence. You have certainly been extremely fortunate so far, and if you preferred a civil appointment you would be pretty certain of getting one when the war is over. There will be a big job in organizing this country after the Dervishes are smashed up, and a biggish staff of officials will be wanted. No doubt most of these will be Egyptians, but Egyptian officials want looking after, so that a good many berths must be filled by Englishmen, and Englishmen with a knowledge of Arabic and the negro dialect are not very easily found. I should say that there will be excellent openings for young men of capacity."

"I have no doubt there will," Gregory said. "I have really never thought much about the future. My attention from childhood has been fixed upon this journey to the Soudan, and I never looked beyond it, nor did my mother discuss the future with me. Doubtless she would have done so had she lived, and these papers I have may give me her advice and opinion about it."

"Well, I must be going on deck," Captain Keppel said. " We shall start in half an hour."

The three gun-boats were all of the same design. They were flat-bottomed, so as to draw as little water as possible, and had been built and sent out in sections from England. They were constructed entirely of steel, and had three decks, the lower one having loophole shutters for infantry fire. On the upper deck, which was extended over the whole length of the boat, was a conning-tower. In the after-portion of the boat, and beneath the upper deck, were cabins for officers. Each boat carried a twelve-pounder quick-firing gun forward, a howitzer, and four Maxims. The craft were a hundred and thirty-five feet long, with a beam of twenty-four feet, and drew only three feet and a half of water. They were propelled by a stern-wheel.

At half-past nine the Zafir's whistle gave the signal, and she and her consorts—the Nazie and Fatteh —cast off their warps and steamed out into the river. Each boat had on board two European engineers, fifty men of the 9th Soudanese, two sergeants of royal marine artillery, and a small native crew.

" I expect that we shall not make many more trips down to Berber," the Commander said, when they were once fairl} T off. "The camp at Atbara will be our head-quarters, unless indeed Mahmud advances, in which case of course we shall be recalled. Until then we shall be patrolling the river up to Metemmeh, and making, I hope, an occasional rush as far as the next cataract."

When evening came on, the steamer tied up to an island a few miles north of Shendy. So far they had seen no hostile parties—indeed the country was wholly deserted. Next morning they started before daybreak; Shendy seemed to be in ruins; two Arabs only were seen on the bank. A few shots were fired into the town, but there was no reply. Half an hour later Metemmeh was seen. It stood half a mile from the river. Along the bank were seven mud forts with extremely thick and solid walls. Keeping near the opposite bank the gun-boats, led by the Zafir, made their way up the river. Dervish horsemen could be seen riding from fort to fort, doubtless carrying orders. The river was some four thousand yards wide, and at this distance the gun-boats opened fire at the two nearest forts. The range was soon obtained to a nicety, and the white sergeants and native gunners made splendid practice, every shell bursting upon the forts, while the Maxims speedily sent the Dervish horsemen galloping off to the distant hills, on which could be made out a large camp.

The Dervish gunners replied promptly, but the range was too great for their old brass guns. Most of the shot fell short, though a few, fired at a great elevation, fell beyond the boats. One shell, however, struck the Zafir, passing through the deck and killing a Soudanese, and a shrapnel-shell burst over the Fatteh. After an hour's fire at this range the gun-boats moved up opposite the position and again opened fire with shell and shrapnel, committing terrible havoc on the forts, whose fire presently slackened suddenly. This was explained by the fact that as the gun-boats passed up they saw that the embrasures of the forts only commanded the approach from the north, and that, once past them, the enemy were unable to bring a gun to bear upon the boats. Doubtless the Dervishes had considered it was impossible for any steamer to pass up under their fire, and that it was therefore unnecessary to widen the embrasures so that the guns could fire upon them when facing the forts or going beyond them.

Читать дальше