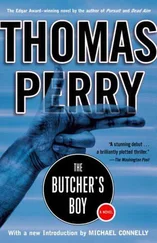

“A couple of hours ago in New York a man walked in the back door of a restaurant and put a hole in Tony Talarese’s head.”

“Tony T?” What surprised her was that she remembered who that was. She could be away for a hundred years, and she couldn’t get the names out of her memory.

“There’s only one suspect. He did it in front of Talarese’s brother, his wife and three mistresses.”

“Interesting. Who was it?”

“The Butcher’s Boy.” But she wasn’t really listening, because there was no other reason why this man would call her at this hour. She was already thinking way ahead: about the kids’ babysitter, about the problem of arranging a temporary transfer out of her section when everybody was working double shifts tracing money from Housing and Urban Development into private bank accounts and about the dress at the dry cleaner’s that she wished she could wear if she had to go into that office again. Part of her was also listening to the baby monitor, because Amanda was beginning to change her tone subtly, occasionally pausing in her quiet babble to issue little bulletins of discomfort.

Richardson gave her the old desk. It was amazing that it even existed; no, not that it existed—because anything that had ever been on a government inventory stayed on it—but that it was still here in the same place, not even shifted off the little wooden wedge Elizabeth had jammed under one leg to keep it from wobbling on the uneven floor.

She played the tape recording a second time. The gun was unbelievably loud. She glanced at the report again: .32 caliber. But, of course, he was firing it two feet from the microphone, into Tony T’s head. She listened to the loud scrabbling, tearing sound, and then the woman shrieking, “The son of a bitch is wearing a wire!” She punched the button.

She stood up and walked into what they had called the chief’s office. In the old days she wouldn’t have considered walking into that room without knocking, but Richardson was her contemporary, and, whether he knew it or not, he wasn’t her boss.

He looked up from his desk. “Well?”

“And the grieving widow said it was the Butcher’s Boy?”

“She said that’s what her brother-in-law told her. He, of course, won’t tell anybody anything.”

“She happen to mention what he’s been doing with himself all these years?”

“I don’t get the impression she’d ever heard of him before. When we catch him you can fill each other in.”

Elizabeth felt it. She couldn’t help that. But she reminded herself that Richardson wasn’t complicated enough to try to jab the sensitive spots. Those ten years had been her portion of a decent life, her allotment. She was a widow too. Richardson knew at least that much. She said carefully, “We’re not going to catch him unless we figure things like that out. You called me down here in the middle of the night, so help me.”

Richardson pushed aside his papers and looked at her evenly. “Right.”

“What were they doing in a closed restaurant—a party?”

“Hardly,” said Richardson. “There was an empty hearse in the back lot. They were going to the airport to pick up Tony’s nephew. It’s been a bad week for Clan Talarese.”

“He was killed too? Where?”

“England.”

She jumped up. “My God, we’re wasting time. Get me the flight lists from London to New York. Every flight since the nephew died. And every flight out of New York since he killed Tony T.”

“You’re jumping to conclusions. We don’t even know what happened to the nephew. It might have been AIDS.”

“Then find out. But later. First the airline flight lists.”

Elizabeth worked alone. In the old days it used to take hours of negotiations to get anything from the airlines. Now any question from the Justice Department—at least the Washington office-induced a special kind of panic. Too many planes had been dropping out of the sky. The fax machine kept buzzing, and Richardson’s secretary had to keep walking back into the little cubicle to change the paper.

Elizabeth crossed off all the names of women, then all the names of travelers with Frequent Flyer credits, then all the reservations made more than a week ago, then all the passengers with names he couldn’t be expected to use—Yamaguchi, Babatundi, Gupta, Hernandez and Nguyen—then looked through the sheets again. What else? What was it that made him special? Nothing. That had to be it. There would be nothing special at all: no special seat, special meals, special luggage arrangements. He didn’t give a damn if he rode naked in the baggage compartment; all he wanted was to get out fast and disappear again. She checked the notations on the printouts once more, crossing off any passenger who had a special request.

That left an encouragingly short list. There wasn’t time to count the names, but there were still too many. She thought about what he had done. He had walked into a kitchen, shot Tony T in front of a lot of people and walked out. It was the middle of the night. Of course he had known Tony T was dangerous. What he would have wanted to do was to sneak into Talarese’s bedroom while he was asleep and empty the pistol into his head. It would have been between three and five in the morning, the time the police always picked for a raid, when he would be deep asleep, and the plane reservation would be based on what he had wanted to do, not what he’d had to do. He would expect to be finished and on the street by five-thirty at the latest, at the airport again by six-thirty and on a plane by seven-thirty or eight. That was the absolute outside limit.

Elizabeth pushed aside half of the flights. Would he sit around in an airport until 10:55 waiting for a way out, when anybody could walk in and see him? Not a chance. He would be long gone by then. He’d be up in the air about thirty thousand feet on his way to … where? Not someplace where there would be two flights a day, eight hours apart. If he missed the first one, there had to be another one warming its engines on the runway. Someplace big and busy. She went through the pile of flights again, pulling out the small cities, losing hundreds of names as she did it, and feeling warmer now, closer to him. Once, years ago, she had gone through the airline lists, knowing that he was one of the names, and never gotten this close. He had already landed somewhere before she even knew he had taken a plane. But this time was different; these flights were still in the air. Maybe this time.

He was running, and he wasn’t going to cross his own path. No return reservation. She obliterated all the round-trip tickets, now finding reasons for eliminating names faster than her hand could move to strike them out. Almost all the remaining names had booked return flights.

Form of payment. He would certainly have credit cards, probably in a lot of different names. But if he did, he wasn’t going to let them be used to trace him away from the crime scene, and he wasn’t going to throw one away for an airline ticket. He would use them for hotels after he had come to earth someplace safe. He would pay cash for the ticket.

There were only five names remaining on three flight lists now, and she laid them all out on the table and stared at them. One of them looked wrong: Hagedorn, David. She was sure she had crossed that one off already. She looked quickly from sheet to sheet. Hagedorn, Mary, traveling with Hagedorn, Marissa. Parents. At one time she wouldn’t have understood, but now she did. It was that awful, depressing anxiety that one of the planes was going to fall out of the sky, and some sort of magic would keep Marissa from being an orphan. She crossed off Hagedorn, David.

There was nothing to distinguish any of the other four. They had all bought tickets with cash on the day of the flight. All had chosen to leave New York on morning flights. All were males traveling alone, taking any seat they could get. Somebody undoubtedly had heard a relative was sick, another had been called for a job interview, another had a girlfriend who wanted him to join her after all. The fourth had just fired a pistol into the head of a New York caporegima, and was understandably impatient to get out.

Читать дальше