Ariely, Dan - The (Honest) Truth About Dishonesty - How We Lie to Everyone – Especially Ourselves

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Ariely, Dan - The (Honest) Truth About Dishonesty - How We Lie to Everyone – Especially Ourselves» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Жанр: Старинная литература, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:The (Honest) Truth About Dishonesty: How We Lie to Everyone – Especially Ourselves

- Автор:

- Жанр:

- Год:неизвестен

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:4 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

The (Honest) Truth About Dishonesty: How We Lie to Everyone – Especially Ourselves: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «The (Honest) Truth About Dishonesty: How We Lie to Everyone – Especially Ourselves»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

The (Honest) Truth About Dishonesty: How We Lie to Everyone – Especially Ourselves — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «The (Honest) Truth About Dishonesty: How We Lie to Everyone – Especially Ourselves», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

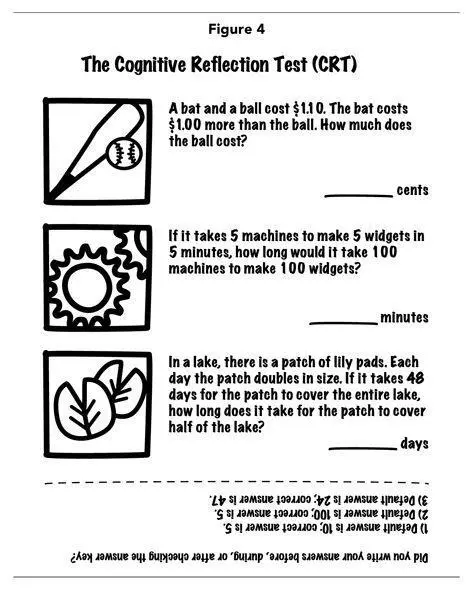

To give you an example, try this one: “A bat and a ball cost $1.10 in total. The bat costs $1.00 more than the ball. How much does the ball cost?”

Quick! What’s the answer?

Ten cents?

Good try, but no. It’s the seductive answer, but not the right one.

Although your intuition prods you to answer “$0.10,” if you rely on logic more than intuition, you’ll check your answer just to be sure: “If the ball were $0.10, the bat would be $1.10, which combine to equal $1.20, not $1.10 (.1 + (1 + .1) = 1.2)! Once you realize that your initial instinct is wrong, you enlist your memory of high school algebra and produce the correct solution (.05 + (1 + .05) = 1.1): 5 cents. Doesn’t it feel like the SATs all over again? And congratulations if you got it right. (If not, don’t worry, you would have most likely aced the two other questions on this short test.)

Next, we measure your intelligence through a verbal test. Here you’re presented with a series of ten words (such as “dwindle” and “palliate”), and for each word you have to choose which of six options is closest in meaning to the target word.

A week later, you come to the lab and settle into one of the computer-facing chairs. Once you’re situated, the instructions begin: “You’ll be taking part in three different tasks today; these will test your problem-solving abilities, perceptual skills, and general knowledge. For the sake of convenience, we’ve combined them all into one session.”

First up is the problem-solving task, which is none other than our trusty matrix task. When the five minutes for the test are over, you fold your worksheet and drop it into the recycling bin. What do you claim is your score? Do you report your actual score? Or do you dress it up a little?

Your second task, the perceptual skills task, is the dots test. Once again, you can cheat all you want. The incentive is there—you can earn $10 if you cheat in every one of the trials.

Finally, your third and final task is a multiple-choice general-knowledge quiz comprised of fifty questions of varying difficulty and subject matter. The questions include a variety of trivia such as “How far can a kangaroo jump?” (25 to 40 feet) and “What is the capital of Italy?” (Rome). For each correct answer, you receive 10 cents, for a maximum payout of $5. In the instructions for this last test, we ask that you circle your answers on the question sheet before later transferring them to a bubble sheet.

When you reach the end of this quiz, you put down your pencil. Suddenly the experimenter pipes up, “Oh, my gosh! I goofed! I mistakenly photocopied bubble sheets that are already marked with the correct answers. I’m so sorry. Would you mind using one of these premarked bubble sheets? I’ll try to erase all the marks so that they will not show very clearly. Okay?” Of course you agree.

Next the experimenter asks you to copy your answers from the quiz to the premarked bubble sheet, shred the test sheets with your original answers, and only then submit the premarked bubble sheet with your answers in order to collect your payment. Obviously, as you transfer your answers you realize that you can cheat: instead of transferring your own answers to the bubble sheets, you can just fill in the premarked answers and take more money. (“I knew all along that the capital of Switzerland is Bern. I just chose Zurich without thinking about it.”)

To sum things up, you’ve taken part in three tasks in which you can earn up to $20 to put toward your next meal, beer, or textbook. But how much you actually walk away with depends on your smarts and test-taking chops, as well as your moral compass. Would you cheat? And if so, do you think your cheating has anything to do with how smart you are? Does it have anything to do with how creative you are?

Here’s what we found: as in the first experiment, the individuals who were more creative also had higher levels of dishonesty. Intelligence, however, wasn’t correlated to any degree with dishonesty. This means that those who cheated more on each of the three tasks (matrices, dots, and general knowledge) had on average higher creativity scores compared to noncheaters, but their intelligence scores were not very different.

We also studied the scores of the extreme cheaters, the participants who cheated almost to the max. In each of our measures of creativity, they had higher scores than those who cheated to a lower degree. Once again, their intelligence scores were no different.

Stretching the Fudge Factor: The Case for Revenge

Creativity is clearly an important means by which we enable our own cheating, but it’s certainly not the only one. In an earlier book ( The Upside of Irrationality ) I described an experiment designed to measure what happens when people are upset by bad service. Briefly, Ayelet Gneezy (a professor at the University of California, San Diego) and I hired a young actor named Daniel to run some experiments for us in local coffee shops. Daniel asked coffee shop patrons to participate in a five-minute task in return for $5. When they agreed, he handed them ten sheets of paper covered with random letters and asked them to find as many identical adjacent letters as they could and circle them with a pencil. After they finished, he returned to their table, collected their sheets, handed them a small stack of bills, and told them, “Here is your $5, please count the money, sign the receipt, and leave it on the table. I’ll be back later to collect it.” Then he left to look for another participant. The key was that he gave them $9 rather than $5, and the question was how many of the participants would return the extra cash.

This was the no-annoyance condition. Another set of customers—those in the annoyance condition—experienced a slightly different Daniel. In the midst of explaining the task, he pretended that his cell phone was vibrating. He reached into his pocket, took out the phone, and said, “Hi, Mike. What’s up?” After a short pause, he would enthusiastically say, “Perfect, pizza tonight at eight thirty. My place or yours?” Then he would end his call with “Later.” The whole fake conversation took about twelve seconds.

After Daniel slipped the cell phone back into his pocket, he made no reference to the disruption and simply continued describing the task. From that point on, everything was the same as in the no-annoyance condition.

We wanted to see if the customers who had been so rudely ignored would keep the extra money as an act of revenge against Daniel. Turns out they did. In the no-annoyance condition 45 percent of people returned the extra money, but only 14 percent of those who were annoyed did so. Although we found it pretty sad that more than half the people in the no-annoyance condition cheated, it was pretty disturbing to find that the twelve-second interruption provoked people in the annoyance condition to cheat much, much more.

In terms of dishonesty, I think that these results suggest that once something or someone irritates us, it becomes easier for us to justify our immoral behavior. Our dishonesty becomes retribution, a compensatory act against whatever got our goat in the first place. We tell ourselves that we’re not doing anything wrong, we are only getting even. We might even take this rationalization a step further and tell ourselves that we are simply restoring karma and balance to the world. Good for us, we’re crusading for justice!

MY FRIEND AND New York Times technology columnist David Pogue captured some of the annoyance we feel toward customer service—and the desire for revenge that comes with it. Anyone who knows David would tell you that he is the kind of person who would gladly help anyone in need, so the idea that he would go out of his way to hurt anyone is rather surprising—but when we feel hurt, there is hardly a limit to the extent to which we can reframe our moral code. And David, as you’ll see in a moment, is a highly creative individual. Here is David’s song (please sing along to the melody of “The Sounds of Silence”):

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «The (Honest) Truth About Dishonesty: How We Lie to Everyone – Especially Ourselves»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «The (Honest) Truth About Dishonesty: How We Lie to Everyone – Especially Ourselves» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «The (Honest) Truth About Dishonesty: How We Lie to Everyone – Especially Ourselves» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.