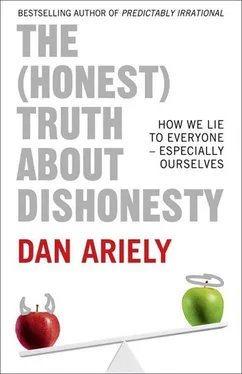

Ariely, Dan - The (Honest) Truth About Dishonesty - How We Lie to Everyone – Especially Ourselves

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Ariely, Dan - The (Honest) Truth About Dishonesty - How We Lie to Everyone – Especially Ourselves» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Жанр: Старинная литература, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:The (Honest) Truth About Dishonesty: How We Lie to Everyone – Especially Ourselves

- Автор:

- Жанр:

- Год:неизвестен

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:4 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

The (Honest) Truth About Dishonesty: How We Lie to Everyone – Especially Ourselves: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «The (Honest) Truth About Dishonesty: How We Lie to Everyone – Especially Ourselves»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

The (Honest) Truth About Dishonesty: How We Lie to Everyone – Especially Ourselves — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «The (Honest) Truth About Dishonesty: How We Lie to Everyone – Especially Ourselves», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

This is why we also had the no-information (control) condition, in which we didn’t mention anything about whether the sunglasses were real or fake. How would the no-information condition help us? Let’s say that women wearing the fake glasses cheated at the same level as those in the no-information condition. If that were the case, we could conclude that the counterfeit label did not make the women any more dishonest than they were naturally and that the genuine label was causing higher honesty. On the other hand, if we saw that the women wearing the real Chloé sunglasses cheated at the same level as those in the no-information condition (and much less than those in the fake-label condition), we would conclude that the authentic label did not make the women any more honest than they were naturally and that the fake label was causing women to behave less honestly.

As you’ll recall, 30 percent of women in the authentic condition and 73 percent of women in the fake-label condition overreported the number of matrices they solved. And in the no-information condition? In that condition 42 percent of the women cheated. The no-information condition was between the two, but it was much closer to the authentic condition (in fact, the two conditions were not statistically different from each other). These results suggest that wearing a genuine product does not increase our honesty (or at least not by much). But once we knowingly put on a counterfeit product, moral constraints loosen to some degree, making it easier for us to take further steps down the path of dishonesty.

The moral of the story? If you, your friend, or someone you are dating wears counterfeit products, be careful! Another act of dishonesty may be closer than you expect.

The “What-the-Hell” Effect

Now let’s pause for a minute to think again about what happens when you go on a diet. When you start out, you work hard to stick to the diet’s difficult rules: half a grapefruit, a slice of dry multigrain toast, and a poached egg for breakfast; turkey slices on salad with zero-calorie dressing for lunch; baked fish and steamed broccoli for dinner. As we learned in the preceding chapter, “Why We Blow It When We’re Tired,” you are now honorably and predictably deprived. Then someone puts a slice of cake in front of you. The moment you give in to temptation and take that first bite, your perspective shifts. You tell yourself, “Oh, what the hell, I’ve broken my diet, so why not have the whole slice—along with that perfectly grilled, mouthwatering cheeseburger with all the trimmings I’ve been craving all week? I’ll start anew tomorrow, or maybe on Monday. And this time I’ll really stick to it.” In other words, having already tarnished your dieting self-concept, you decide to break your diet completely and make the most of your diet-free self-image (of course you don’t take into account that the same thing can happen again tomorrow and the day after, and so on).

To examine this foible in more detail, Francesca, Mike, and I wanted to examine whether failing at one small thing (such as eating one french fry when you’re supposedly on a diet) can cause one to abandon the effort altogether.

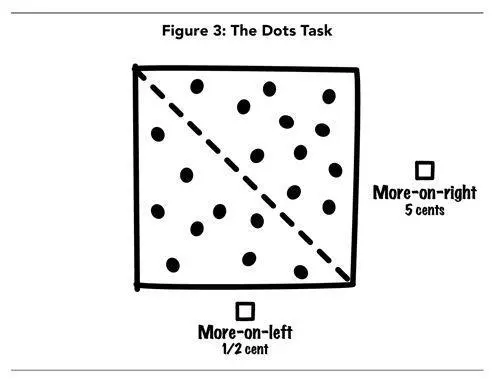

This time, imagine you’re wearing a pair of sunglasses—whether they are authentic Chloé, a fake pair, or a pair of unspecified authenticity. Next, you sit down in front of a computer screen where you’re presented with a square divided into two triangles by a diagonal line. The trial starts, and for one second, twenty randomly scattered dots flash within the square (see the diagram below). Then the dots disappear, leaving you with an empty square, the diagonal line, and two response buttons, one marked “more-on-right” and the other marked “more-on-left.” Using these two buttons, your task is to indicate whether there were more dots on the right-hand or left-hand side of the diagonal. You do this one hundred times. Sometimes the right-hand side clearly has more dots. Sometimes they are unmistakably concentrated on the left-hand side. Other times it’s hard to tell. As you can imagine, you get pretty used to the task, as tedious as it may be, and after a hundred responses the experimenter can tell how accurately you can make these sorts of judgments.

Next, the computer asks you to repeat the same task two hundred more times. Only this time, you will be paid according to your decisions. Here’s the key detail: regardless of whether your responses are accurate or not, every time you select the left-hand button, you will receive half a cent and every time you select the right-hand button, you will receive 5 cents (ten times more money).

With this incentive structure, you are occasionally faced with a basic conflict of interest. Every time you see more dots on the right, there is no ethical problem because giving the honest answer (more on the right) is the same response that makes you the most money. But when you see more dots on the left, you have to decide whether to give the accurate honest answer (more on the left), as you were instructed, or to maximize your profit by clicking the more-on-right button. By creating this skewed payment system, we gave the participants an incentive to see reality in a slightly different way and cheat by excessively clicking the more-on-right button. In other words, they were faced with a conflict between producing an accurate answer and maximizing their profit. To cheat or not to cheat, that was the question. And don’t forget, you’re doing this while still wearing the sunglasses.

As it turned out, our dots task showed the same general results as the matrix task, with lots of people cheating but just by a bit. Interestingly, we also saw that the amount of cheating was especially large for those wearing the fake sunglasses. What’s more, the counterfeit wearers cheated more across the board. They cheated more when it was hard to tell which side had more dots, and they cheated more even when it was clear that the correct answer was more on the left (the side with the lower financial reward).

Those were the overall results, but the reason we created the dots task in the first place was to observe how cheating evolves over time in situations where people have many opportunities to act dishonestly. We were interested in whether our participants started the experiment by cheating only occasionally, trying to maintain the belief that they were honest but at the same time benefitting from some occasional cheating. We suspected that this kind of balanced cheating could last for a while but that at some point participants might reach their “honesty threshold.” And once they passed that point, they would start thinking, “What the hell, as long as I’m a cheater, I might as well get the most out of it.” And from then on, they would cheat much more frequently—or even every chance they got.

The first thing that the results revealed was that the amount of cheating increased as the experiment went on. And as our intuitions had suggested, we also saw that for many people there was a very sharp transition where at some point in the experiment, they suddenly graduated from engaging in a little bit of cheating to cheating at every single opportunity they had. This general pattern of behavior is what we would expect from the what-the-hell effect, and it surfaced in both the authentic and the fake conditions. But the wearers of the fake sunglasses showed a much greater tendency to abandon their moral constraints and cheat at full throttle. *

In terms of the what-the-hell effect, we saw that when it comes to cheating, we behave pretty much the same as we do on diets. Once we start violating our own standards (say, with cheating on diets or for monetary incentives), we are much more likely to abandon further attempts to control our behavior—and from that point on there is a good chance that we will succumb to the temptation to further misbehave.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «The (Honest) Truth About Dishonesty: How We Lie to Everyone – Especially Ourselves»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «The (Honest) Truth About Dishonesty: How We Lie to Everyone – Especially Ourselves» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «The (Honest) Truth About Dishonesty: How We Lie to Everyone – Especially Ourselves» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.