Anthony Summers - The Eleventh Day

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Anthony Summers - The Eleventh Day» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Жанр: Старинная литература, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:The Eleventh Day

- Автор:

- Жанр:

- Год:неизвестен

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:3 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

The Eleventh Day: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «The Eleventh Day»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

The Eleventh Day — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «The Eleventh Day», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

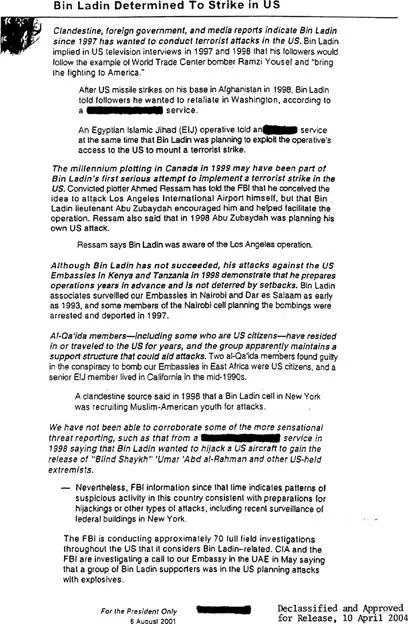

Prior to the August 6 PDB, the President said, no one had told him al Qaeda cells were present in the United States. “How was this possible?” Ben-Veniste wrote later. “Richard Clarke had provided this information to Condoleezza Rice, and he had put it in writing.” Indeed he had, on two occasions. Three weeks earlier, Ben-Veniste had asked Rice whether she told the President prior to August 6 of the existence of al Qaeda cells in the United States. After much prevarication, she replied: “I really don’t remember.”

As for the reference in the PDB to recent surveillance of buildings in New York—known to relate to two Yemenis who had been arrested after taking photographs—the President quoted Rice as having told him the pair were just tourists and the matter had been cleared up. If so, that, too, was strange. The FBI had not cleared the matter up satisfactorily. Agents tried in vain to find the man who, using an alias, had asked that the photographs be taken. The unidentified man had wanted them urgently, even asking that they be sent to him by express mail.

What then, Ben-Veniste asked, did the President make of his national security adviser’s claim that nobody could have foreseen terrorists using planes as weapons? How to credit that, in light of the warnings in summer 2001 that the G8 summit in Genoa might be attacked by airborne kamikazes? Had Bush known about the Combat Air Patrol enforced over cities he visited in Italy? Had he known about the Egyptian president’s warning? No, Bush said, he had known nothing about it.

If there had been a “serious concern” in the weeks before 9/11, Bush volunteered, he would have known about it. Ben-Veniste restrained himself from pointing out that the CIA brief of August 6 had been headed “Bin Laden Determined to Strike in U.S.” Had the President not rated that as “serious”?

Ben-Veniste asked Bush whether, after receiving the PDB, he had asked National Security Adviser Rice to follow up with the FBI. Had she done so? The President “could not recall.” Nor could he remember whether he or Rice had discussed the PDB with Attorney General Ashcroft.

There is another, bizarre and unresolved, anomaly. Rice—and Bush—have said the national security adviser was not present during the August 6 briefing at the President’s ranch. She was in Washington, she said, more than a thousand miles away. CIA director Tenet, however, told the Commission in a formal letter that Rice was present that day.

Finally, and for a number of reasons, there is doubt as to whether the Agency produced the relevant section of the August 6 PDB because—as Rice indicated and Bush flatly claimed—he had himself “asked for it.”

Had he really requested the briefing? It is reliably reported that, having received it, Bush responded merely with a dismissive “All right. You’ve covered your ass now.” Ben-Veniste has made the reasonable point that if the President himself had called for the briefing, his response would hardly have been so flippant.

The President had indeed asked over the weeks whether available intelligence pointed to an internal threat, Director Tenet was to advise the Commission in a formal letter. But: “There was no formal tasking.”

According to Ben-Veniste’s account, the two analysts who drafted the PDB told him that “none of their superiors had mentioned any request from the President as providing the genesis for the PDB. Rather, said Barbara S. and Dwayne D., they had jumped at the chance to get the President thinking about the possibility that al Qaeda’s anticipated spectacular attack might be directed at the homeland.”

The threat, they thought, had been “current and serious.” CIA officials, sources later told The New York Times ’s Philip Shenon, had called for the August 6 brief to get the White House to “pay more attention” to it.

The Agency analysts, Ben-Veniste reflected, “had written a report for the President’s eyes to alert him to the possibility that bin Laden’s words and actions, together with recent investigative clues, pointed to an attack by al Qaeda on the American homeland. Yet the President had done absolutely nothing to follow up.”

WHAT THEN of the time between August 6 and September 11, the precious thirty-six-day window during which the terrorists could conceivably perhaps have been thwarted? There were two major developments in that time, both of which—with adroit handling, hard work, and good luck—might have averted catastrophe.

The first potential break came on August 15, when a manager at the Pan Am International Flight Academy in Minneapolis phoned the local FBI about an odd new student named Zacarias Moussaoui. Thirty-three-year-old Moussaoui, born in France to Moroccan parents, had applied for a course at the school two months earlier, saying in his initial email that his “goal, his dream” was to pilot “one of these Big Bird.” That he as yet had no license to fly even light aircraft appeared to discourage Moussaoui not at all. “I am sure that you can do something,” he had written, “after all we are in AMERICA, and everything is possible.”

It happened on occasion that some dilettante applied to buy training time on Pan Am’s Boeing 747 simulator. Moussaoui himself was to say that the experience would be “a joy ride,” “an ego boosting thing.” The school did not necessarily turn away such aspirants. Moussaoui arrived, paid the balance of the fee—$6,800 in cash he pulled out of a satchel—saying that he wanted to fly a simulated flight from London to New York’s JFK Airport. At his first session he asked a string of questions, about the fuel capacity of a 747, about how to maneuver the plane in flight, about the cockpit control panel—and what damage the airliner would cause were it to collide with something.

Sensing that this student was no mere oddball, that he might have evil intent, the school’s instructors agreed that the FBI should be contacted. The reaction at the Minneapolis field office was prompt and effective. Moussaoui was detained on the ground that his visa had expired, and agents began questioning him and a companion—a Yemeni traveling on a Saudi passport. They learned rapidly that Moussaoui was a Muslim, a fact he had denied to his flight instructor.

The companion, moreover, revealed that the suspect had fundamentalist beliefs, had expressed approval of “martyrs,” and was “preparing himself to fight.” Within the week, French intelligence responded to a request for assistance with “unambiguous” information that Moussaoui had undergone training at an al Qaeda camp in Afghanistan.

One of the Minneapolis agents, a former intelligence officer, felt from early on “convinced … a hundred percent that Moussaoui was a bad actor, was probably a professional mujahideen” involved in a plot. Though he and his colleagues had no way of knowing it at the time, their suspicions were well founded. KSM would one day tell his interrogators that Moussaoui had been slated to lead a second wave of 9/11-type attacks on the United States. In a post-9/11 climate, KSM had assumed, the authorities would be especially leery of those with Middle Eastern identity papers. In those circumstances, and though Moussaoui was a “problematic personality,” his French passport might prove a real advantage. Osama bin Laden, moreover, favored finding a role for him.

Before flying into the States, the evidence would eventually indicate, Moussaoui had met in London with Ramzi Binalshibh. Binalshibh had subsequently wired him a total of $14,000. Binalshibh’s telephone number was listed in one of Moussaoui’s notebooks and on other pieces of paper, and he had called it repeatedly from pay phones in the United States.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «The Eleventh Day»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «The Eleventh Day» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «The Eleventh Day» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.