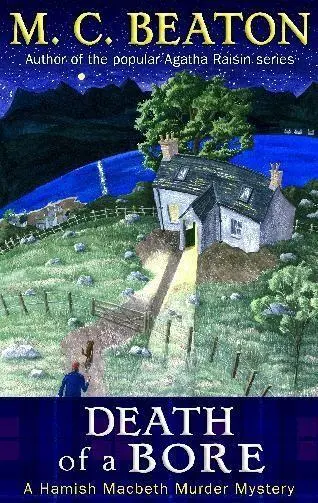

M.C. Beaton

Death of a Bore

Hamish Macbeth #21

2005, EN

∨ Death of a Bore ∧

1

No man, but a blockhead, ever wrote, except for money .

—Samuel Johnson

There used to be quite a lot going on in a highland village during the long, dark winter months. There was a ceilidh every week where the locals danced or performed, singing the old songs or reciting poetry. Often there was a sewing circle with its attendant gossip; the Mothers’ Union meetings; the Girl Guides and Boy Scouts classes; and the weekly film show in the village hall. But with the advent of television and videos, people often preferred to stay cosily indoors, being amused by often violent films with heroines with high cheekbones, collagen-enhanced lips, and heels so high it made ankles comfortably ending in slippered feet just ache to look at them.

Therefore when Hamish Macbeth, police constable of Lochdubh, heard that a newcomer, John Heppel, was planning to hold a series of writers’ classes in the village hall, he set out to dissuade him. As he said to his fisherman Mend, Archie Maclean, “I don’t want to see the poor wee man humiliated when nobody turns up.” Hamish had seen a poster in Patel’s general store:

DO YOU WANT TO BE A FAMOUS WRITER? FAMOUS WRITER JOHN HEPPEL WILL HELP YOU BECOME ONE.

The first meeting was scheduled for the following week on a Wednesday evening at seven-thirty. Hamish knew that on that evening Petticoat Cops was showing at just that time, a cop series set in LA with three leggy blondes with large lips, high busts, and an amazing skill with firearms and kung fu. He did not know anyone in Lochdubh who would risk missing the latest episode, except perhaps himself.

So on one wet black evening with a gusty gale blowing in from the Atlantic and ragged clouds ripping across the sky, Hamish got into the police Land Rover and set out for John’s cottage, which was out on the moors above the village of Cnothan. Hamish was feeling lonely. His affair with the local reporter, Elspeth Grant, had come to an abrupt halt. She had been offered a job on a Glasgow newspaper and had asked him bluntly if he meant to marry her.

And Hamish had dithered, then he had said he’d think about it, and by the time he had got around to really considering the idea, Elspeth had accepted the job and left. He wondered gloomily whether he was cut out to live with anyone, for his first feeling on hearing the news that she had gone was one of relief.

He wondered at first why John had not decided to hold his classes in Cnothan but then reflected that Cnothan was a sour town and specialised in ostracising newcomers.

Sergeant MacGregor, who had policed Cnothan for years, had retired, and the village and surrounding area had been added on to Hamish’s already extensive beat. Village police stations were being closed down all over the place, and Hamish had not felt strong enough to protest at the extra work in case he lost his beloved home in the police station in Lochdubh.

Hamish had never met John Heppel. Normally he would have made a courtesy call, but an irritating series of burglaries over in Braikie had to be solved, and somehow the man’s arrival in the Highlands had gone out of his mind. Much as he loved Sutherland and could not consider living anywhere else, Hamish knew that newcomers often relocated to the far north of Scotland through misguided romanticism. Writers or painters imagined that the solitude and wild scenery would inspire them, but usually it was the very long dark winters that finally defeated them.

He drove through Cnothan, bleak and rain-swept under the orange glare of sodium lights, and up onto the moors. The heathery track leading to John’s cottage had a poker-work sign pointing the way. It said, “Writer’s Folly.”

Hamish drove along the track and parked outside the low whitewashed cottage that was John’s home.

Hamish chided himself for not phoning first. He rapped on the door and waited while the rising gale whipped at his oilskin coat.

A small man opened the door and stared up at the tall policeman. “I am Police Constable Hamish Macbeth from Lochdubh,” said Hamish. “Might I be having a wee word with you?”

“Come in.”

Hamish followed him into a living room lined with books. A computer stood on a table by the window. Peat smouldered on the open fire. Over the fireplace hung a large framed photograph of the author accepting a plaque.

“You have interrupted my muse,” said John, and gave a great hee-haw sort of laugh.

He was only a little over five feet tall, bespectacled, with thinning grey hair, the strands combed over a balding scalp. His eyes were large and brown above a squashy, open-pored nose and fleshy mouth. He wore a roll-necked brown sweater and brown cords.

“Sit down,” he said. “You’re making my neck ache.”

Hamish removed his cap and coiled his lanky length down into an armchair by the fire.

“Is that your own colour?” asked John, staring at Hamish’s flaming-red hair.

“All my own. You don’t seem to be surprised at getting a visit from the police.”

“I’m not married, my parents are dead, and I have no close relatives. People are only frightened when they see a policeman at the door if they’re worried about a loved one or have something to hide. So why have you come?”

“It’s about your writing class.”

“I’ll be delighted to see you there. You can pay for the whole term or at each class.”

“I wasn’t thinking of attending. I don’t think anyone will. They’ll all be at home watching the telly.”

John looked a trifle smug. “I have already had ten applications from the residents of Lochdubh.”

“Who might they be?”

“Ah.” John wagged a finger. “I suggest you come along and see.”

“I might do that. Have you had much published?”

“I received the Tammerty Biscuit Award for Scottish literature.” John pointed to the photograph. “That’s me getting the award for my book Tenement Days . Have you read it?”

“No.”

“Then let me give you a copy.” John left the room. Hamish looked around. A small table over against the wall opposite from the computer held the remains of a meal. Apart from the books lining the low walls and the large photograph over the fireplace, there were no ornaments or family photographs.

John came back in and handed him a copy of Tenement Days . “I signed it,” he said. Hamish flipped it open and looked at the inscription. It read, “To Hamish MacBeth. His first introduction to literature. John Heppel.”

“I haff read other books,” said Hamish crossly, the sudden sibilance of his highland accent showing he was annoyed. “And my name is spelled without a capital B . What else have you written?”

“Oh, lots,” said John. “I’ve just finished a film script for Strathbane Television.”

“What’s it called?”

John looked suddenly uncomfortable. “Well, it’s a script for Down in the Glen ”

Hamish smiled. “That’s a soap.”

“But I have raised the tone, don’t you see? To improve the public mind, even great authors such as myself must lower themselves to write for a popular series.”

“Indeed? Good luck to you. I had better be going.”

“Wait a bit. You asked about my work? I have been greatly influenced by the French authors such as Jean-Paul Sartre and François Mauriac. Even when I was at school, I became aware that I had a great gift. I was brought up in the mean streets of Glasgow, a hard environment for a sensitive boy. But I observed. I am a camera. I sometimes feel I have been sent down from another planet to observe.”

Читать дальше