‘As you know, our situation is precarious,’ said Holmes. He paused, but no one said a word. ‘In addition to the question of our personal safety, we have the responsibility of completing our mission and delivering the plans to the American authorities.’

Holmes’s hands were pointing forwards, with fingertips touching, as he stared into the flames. I had often seen him in this pose at our Baker Street flat, mostly when he was deep in thought.

‘Miss Norton,’ he said, ‘you must board a lifeboat as quickly as possible. It is your responsibility to ensure that the plans arrive safely.’

For a moment, it appeared that our young friend was going to raise her voice in objection. But she stopped short when Holmes turned his head to look at her.

‘Yes, Mr Holmes, I will.’

‘And Miss Storm-Fleming, I consider it your duty to accompany Miss Norton. In view of all the efforts that have been made to steal the plans thus far, she might need your help.’

Miss Storm-Fleming left her chair and sat on the floor in front of me, next to the fire. She smiled at him, then turned to the fire and began to warm her hands. ‘My superiors gave me two assignments. One was to look after the submarine plans. The other was to make contact with you at the end of the voyage and take you to your American contact. If I let you drown, I will have failed in one of my missions. That would taint my record.’

‘Miss Storm-Fleming, you must get to a lifeboat,’ I said. ‘Holmes and I will proceed shortly, after a rescue ship arrives. This is not certain, but the odds are with us.’

‘Well, Watson,’ said Holmes. ‘If I thought it would do any good, I would tell you to try to get into a lifeboat too. They might allow men to board later on. But I know what the answer would be. So perhaps you would like to accompany me in a search for Moriarty. There are one or two matters of interest that I would like to discuss with him.’

‘Are you not forgetting that we have friends on board? Mr Futrelle and his wife, especially,’ said Miss Norton. ‘Should we not we find them and try to warn them?’

‘And young Tommy and his parents...’ added Miss Storm-Fleming.

‘Yes, of course, you are quite right. We must make an effort to find them while there is still time.’

‘It is a large ship,’ I said.

‘Yes, indeed it is,’ Holmes replied. ‘Perhaps we should split up. Miss Norton, please come with me. We’ll search A Deck.’

I looked at Miss Storm-Fleming and she nodded.

‘We will go up to the boat deck.’

‘Very well,’ said Holmes. ‘We will meet again at 1.15. Go to the boat deck below the forward funnel, on the starboard side, but if matters begin to look difficult, please go to a lifeboat.’

Holmes was the first to rise from his chair. Soon, the rest of us headed slowly towards the door.

We paused before leaving. Inside this room there was warmth, elegance and, dare I say it, friendship. But we all knew full well that the clock was ticking. Before the night was out, this luxury room on the world’s largest ocean liner would be filled with icy water and lying on the ocean floor.

Holmes extended his hand to me, and I grasped it firmly.

Then he opened the door.

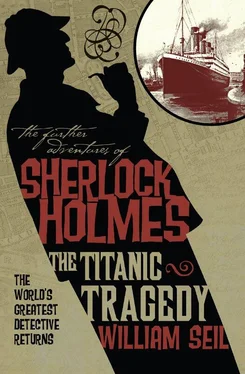

Chapter Twenty-Eight

THE EARLY HOURS OF MONDAY 15 APRIL 1912

The Titanic had developed a perceptible tilt. Both Miss Storm-Fleming and I noticed it immediately as we stepped out on to the boat deck. Much to our surprise, there was no panic. People seemed to realize that the ship was in trouble but they had no idea of their immediate peril. In fact, one member of the crew, who was assisting with the loading of a lifeboat, told me that the Titanic could not possibly sink in less than eight hours — plenty of time for rescue ships to arrive. Speaking as a veteran, it was his opinion that the ship would not sink at all.

‘I may stay on board while the ship is towed back to Belfast,’ he boasted. ‘I will book myself a first-class cabin and have a grand old time.’

The Titanic had sixteen lifeboats under davits, as well as four Englehardt collapsible boats, which were stored elsewhere on the boat deck. Thus far, six of the craft had been launched, none of which had been filled to capacity. The crew was having a difficult time getting people to board the boats. So rather than waiting for greater cooperation from the passengers, they launched them. Officers reasoned that once the boats were safely in the water, they could come back and rescue swimming survivors.

Miss Storm-Fleming and I had a decision to make. With precious moments remaining, was there anything we could do to rally the passengers? Could we save lives by going from group to group, urging people to board the lifeboats? And what if some action on our part had just the opposite effect? A panic might slow the loading of the lifeboats and result in a greater loss of life. And who were we to question the wisdom of an experienced crew? We decided to proceed with our mission and, if possible, offer our assistance to the captain.

We began our search for Tommy and the Futrelles on the starboard side of the ship. There was no sign of them. We were impressed, however, by the sight of the ship’s band standing outside the gymnasium playing lively tunes. I could not help but admire these fine men, whose music did so much to raise the spirits of those on board.

On the port side we found Mr Lightoller preparing to lower a boat. The second officer, while guiding reluctant women and children into the craft, was simultaneously carrying on a conversation with a steward.

‘I am sorry, Hart, I am needed here and I have no one spare. You will have to manage by yourself.’

‘It is the language more than anything, sir,’ said Hart. ‘So many of them cannot understand English. I just cannot persuade them to move. Finns, Swedes, they do not understand.’

‘Perhaps I can help,’ said Miss Storm-Fleming. ‘Linguistics was always one of my stronger subjects.’

Lightoller interrupted his work. ‘Miss Storm-Fleming,’ he said with some surprise. And Doctor Watson. Would you accompany Mr Hart down to steerage?’

‘Yes, of course, just show me where to go,’ said Miss Storm-Fleming.

‘And me too,’ I added.

‘Very good. But make haste,’ said Lightoller. ‘There are still plenty of boats, but they are going fast.’

Hart guided us to the foot of the main steerage staircase, aft on E Deck. The area, surrounded by plain white walls and low ceilings, was mobbed with families. Some appeared frightened, while others just looked confused. I felt especially sorry for a young mother, who was trying to keep her children together amid the moving crowd.

Hart took charge of the situation. ‘I’m going to find the interpreter and see how he is doing. By now, he should have a group assembled to go on deck. Please gather together some families, as many as you can, and follow the same route back to the boat deck. Do you think you can do that?’

‘Indeed,’ I replied.

‘Good luck then, and God bless you.’

Hart disappeared into the crowd.

The steward had not exaggerated the difficulty of the task. It required conveying the urgency of the situation, without creating panic. Miss Storm-Fleming did a magnificent job carrying out her assignment, using several different languages. I helped with the English-speaking families. Soon, we had a group of about thirty people ready to go.

I led the group up the stairs and into the third-class lounge on C Deck. Miss Storm-Fleming took up the rear, ensuring that there were no stragglers. We continued across the open well deck, past the library and into first class. Before long we were making our way up the grand stairway to the boat deck.

Читать дальше