...than monsters.

The children laughed and clapped and Triqueta turned away.

Her mare was jumpy, hooves precarious amid squealing vermin and squawking wildlife, the occasional fallen drunk. Haggling was common, it was vicious and occasionally violent – Larred Jade’s soldiery did not patrol the Fayre and bursts of roughhousing were frequent.

A male voice called to Jayr to join him in an unlikely physical exploration. Jayr coloured, but ignored him. Triq snickered.

As they moved closer to the city, so the stalls became sturdier and more wealthy – their wares better quality and their garbage and chaos significantly less. Here, the city’s defences rose above the morass and Jade’s archers prowled warily, their eyes open.

Ress glanced back at Feren, and they picked up the pace.

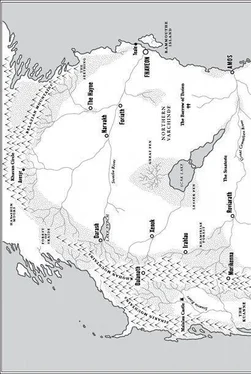

Around them now, shouts offered rare and wondrous metals from the blind craftsmen of the Kartiah; stone from the mountains; wood from the forests that blanketed their feet. From the north, there was food and ale; salt from Fhaveon; spices from Amos; rich fabrics from Padesh and the cities of the far south. Wines flowed from Annondor; from Idrak came the prized hides of the racing arqueus. And everywhere, there was terhnwood, fibre and resin and fragment, the critical life of the Varchinde plains.

Fhaveon had might and Amos wisdom – but traditionally, Roviarath was the Varchinde’s hub. She stood strong at the centre of the Grasslands’ motion and wealth.

Sod that , Triqueta figured, eyeing the mucky mass of stalls. Right now she stood strong at the centre of the Grasslands’ mud. It was everywhere, a sea of it, churned with grass and filth and rubbish.

By morning, the Fayre would be rotting garbage and liquid shit.

Triq’s mare blew water and shook her soaked mane. The wheels of Feren’s cart lurched and splashed.

“Not far!” Ress called.

Jayr grunted and cursed – she was almost wading, the mud caked on her boots. Her scalplock hung heavy, like a horse’s tail, and the rain seemed to run along the lines of her scars.

Triq shivered.

As they came towards the rampart and the gates, rocklights were beginning to flicker, defying the rising dark. In there somewhere, among the pens and the pickets and the flapping stall roofs, there was music, drums and laughter. She could hear the traders calling banter and wares. Here, there were artists and storytellers, sheltering in the lee of the city.

One of them called out as they came past, “Look! Banned! They’ve come to deal with the monsters!”

“Tell the CityWarden!” called another. “There are fires in the farmlands and monsters loose in the plains! Our tithes are failing because our harvest burns!”

“Gods,” Triqueta muttered, spitting water. “It’s everywhere.”

“Yep.” Jayr slipped as her horse buffeted her again. “Will you stop that?”

Strapped in the cart, Feren called at the glowering sky. A frisson shivered through Triq’s hunched and sopping form.

Monsters.

* * *

Roviarath’s gatehouse was built of wood, once mighty but now split and cracked with age and weather. There was no archway, no rampart – the building sat snug between soil battlements that offered a sheltered walkway around their top. In better weather, you could tour the Fayre from above.

Now, though, the walkway contained only archers, dejected in the downpour.

As Triqueta and the others came closer, thumping to a stop with the rain now driving into their backs, they could see the watch-flag, hanging sodden and fluttering occasionally like a dying bird.

Triq shook her hood, wiped her face. She called into the hammering weather, “Triqueta of the Banned! I bear injured!”

“Picked your night for it!” The archers’ commander, their tan, grinned down at her. “Gate’s open, go on in. Did you find your dice?”

“Don’t yank my rope, Cohn.” Triq gave the guardsman a rude hand gesture. “If you know who took them – !”

“No, Triq, I don’t. But I do know I wouldn’t be letting you in city limits if you still had them on you.” His comment was greeted by guffaws from further back.

“Why the watch-flag?” Ress called from the cart. “You got pirate problems?”

“Nah.” The commander took a tiny block of wax from a pouch and rubbed it carefully down his bowstring. “The wild herds’re on the move – they’re much closer to the walls. And it’s not only them – Deep Patrols say bigger beasties have shifted territory, they shot a lone bweao not half a day from the waterside.” He grinned. “Don’t tell me you lot haven’t noticed?”

“Bweao?” Ress chuckled. “They kill it?”

“Fat chance!” The guard commander rolled his eyes, still grinning. “It was a young one, I think – they scared it off.”

Triq spat water. “Storyteller said something about fires?”

“Not in this weather!” The tan laughed at her.

Triq groaned, and then, quite clearly, Feren cried out, “We see all but nothing!”

She turned, but Ress was already moving the cart forwards.

“Kid needs help. Must get to the hospice!”

“No problem!” The commander drew a shaft from the quiver at his belt and notched it, though he didn’t draw the string. He nodded affably as they passed between decaying wooden jaws. “We’ll send a runner up to old man Jade. Hope your lad’s all right, there. And stay out of trouble!”

If he heard Triqueta’s answering chuckle, he made no sign.

* * *

Larred Jade, CityWarden of Roviarath, was a tall man, lean and curved and canny, eyes as blue and clear as the summer sky. In spite of the rain that beat on the windows of the rocklit hospice, his skin was tinged with sunlight. Dark hair was caught in a gleaming metal band at the nape of his neck. White strands glittered through it, like the bright edges of his awareness.

Warden Jade was as sharp as a good blade and a fireblasted hard man to fool. Standing a head taller than his frowning apothecary, he was watching the dying boy that now lay, blood black and parchment white, upon the cool haven of the pallet.

He said, “Monsters.”

Wet garments still stuck to her, dripping rainwater from her hem stitching, Triqueta turned to face him. Her hair was stuck to her like molten metal and the stones in her cheeks flashed, a warning – or a plea.

She said, “I know how it sounds –”

“It’s crazed.” He was tapping long fingers against his thigh – artisan’s fingers, fingers for weaving success. The CityWarden was a merchant, and a very successful one; his knowledge of his craft was absolute.

“I know.” She caught his eye, shrugged at him with deceptive innocence, then her expression sobered. “I saw them, Larred, we all did. I’ve never had anything like that under me. It was like riding a... riding a storm.”

The words were inadequate to the thrill that sang in her blood.

“Address me as Warden Jade.” It was reflex, his tone was both thoughtful and wary. He said, “Half human, half horse, lurking at the borders of the city.”

Watched by a fidgeting Ress, the apothecary was carefully soaking Feren’s bandaging away from the boy’s wounds.

“Too long in the open grass, Triqueta of the Banned, plays games with your sight and memory – and that’s without all the ale,” the Warden said.

“Maybe,” she told him archly, “but it’s not a game when you tear out its cursed throat, feel its blood run down your arm. When you’ve got it under you and you’re fighting for life, for control.” Her hand tensed with the memory – the adrenaline, the fury, the savage and primal release of strength. Her voice alight she said, “I don’t know what they were, Larred, but they’re out there. And the bweao know it – why d’you think that flag’s on your gatehouse?”

Читать дальше