“Rascals” Tad and Willie Lincoln—seven and ten years old, respectively—were the unquestioned life (some would say scourge) of the White House. The boys spent countless hours running rampant over the mansion and its grounds during the first year of their father’s presidency, a fact that aggravated some of Abe’s associates to no end, but offered the president a much-needed distraction from the stresses of running a country and a war.

The sound of my boys at play is (too often, I confess) the only joy between sunrise and sleep. I am therefore too happy to wrestle and chase them about whenever the opportunity presents itself—and regardless of who looks on. Not one week ago, [Iowa Senator James W.] Grimes walked into my office for an appointment, only to find me pinned to the floor by four boys: Tad and Willie holding my legs, Bud and Holly *my arms. “Senator,” I said, “if you would be kind enough to negotiate the terms of my surrender.” Mary thinks it beneath the dignity of a president to gambol so, but were it not for these moments—these tender little pieces of life—I should go mad in a month’s time.

Abe was a doting, loving father to all three of his boys, but with Robert off at Harvard (where he was guarded by a handful of local men and vampires) and Tad “too young and wild to be still,” he grew especially fond of Willie.

He has an insatiable appetite for books; a love of solving riddles. If there is a fight, he can be counted on to step in and make the peace. Some are eager to point to the similarities between us, but I do not see us as so very similar—for Willie has a kinder heart than I, and a quicker mind.

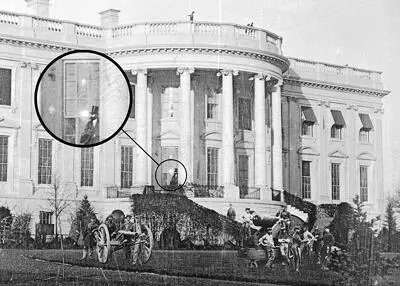

As he celebrated the good news that Sunday afternoon, Abe happened to catch a glimpse of his boys playing on the frost-covered South Lawn below his office window.

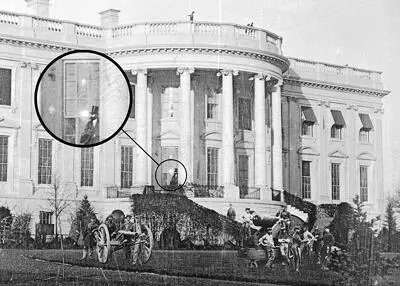

Tad and Willie were busy holding a court-martial for Jack *as they often did—accusing him of this offense or that. Not ten yards from where they played, two young soldiers (not much more than boys themselves) looked after them—both of them shivering, no doubt wondering what they had done to deserve such an assignment.

They were just two of the dozen living guards who patrolled the White House and its grounds around the clock. At Abe’s insistence, his wife and children were accompanied by no fewer than two men (or one vampire) whenever they ventured outdoors. There were no fences between the street and the mansion in 1862. The public was free to roam the grounds—even enter the mansion’s first floor. As journalist Noah Brooks wrote, “the multitude, washed or unwashed, always has free egress and ingress.” The multitude was not, however, permitted to carry firearms onto the property.

At half-past three o’clock, a small, bearded man with a rifle was spotted approaching the White House from the direction of Lafayette Square. The sentry assigned to the North Entrance leveled his weapon and ordered the man to stop—yelling at the top of his lungs.

FIG. 3A-1. - SOUTH LAWN OF THE WHITE HOUSE UNDER HEAVY GUARD, CIRCA 1862. THE MAN ON THE PORTICO IS BELIEVED TO BE A MEMBER OF ABE̱S TRINITY.

The commotion drew me to the north windows, where I watched the little man continue his approach, a rifle held across his body. Guards came running now from every corner of the grounds, alerted, as we had been, by the repeated shouts of “stop at once or be shot!”

Three of these guards came running quite a bit faster than the others, and made straight for the intruder with no fear of being shot. At the sight of their advance (and, I suspect, their fangs), the little man at last dropped his rifle and raised his hands in the air. He was nonetheless brought violently to the ground, and his pockets searched by Lamon while the trinity held his limbs. I was later told that he seemed frightened; confused. “He gave me ten dollars,” he supposedly said with tears in his eyes. “He gave me ten dollars.”

Only now, with the immediate danger passed, did my eyes find two of the several soldiers now forming a circle around the intruder.

Abe’s heart stopped. They were the same young soldiers who’d been looking after Willie and Tad.

His children were alone.

The boys had been too engrossed to pay any mind to the shouting, or notice their shivering guards running off to investigate it. In this vulnerable moment, they were set upon by a stranger.

He, too, might have escaped their notice, had the heel of his boot not come down on their doll and brought an end to their game. Willie and Tad looked up to see a man of average height and build standing over them, wearing a long black coat, with a scarf and top hat to match. His eyes were obscured by dark glasses, and his lip obscured by a thick brown mustache. “Hello, Willie,” he said. “I have a message for your father. I would very much like you to give it to him.”

Now it was Tad’s screams that brought the guards running.

The vampires were the first to arrive, with Lamon and several soldiers on their heels. I came bounding down the steps of the South Portico next, and found Tad frightened and crying, but seemingly unharmed. Willie, however, was rubbing his tongue with his coat sleeve and spitting repeatedly. I took him in my arms and looked him over—turning his face and neck this way, that way—all the while praying there were no wounds on his body.

“There!” Lamon cried, pointing to a figure running south. He and the trinity gave chase, while the others hastened us into the house. “Alive!” I cried after them. “Alive!”

Lamon and the trinity chased the figure across Pennsylvania Avenue and through the Ellipse. *When it became clear that he couldn’t keep pace, the breathless Lamon drew his revolver and, with no regard for the innocent bystanders he might have hit, fired at the distant figure until his cartridges were spent.

The trinity was gaining on its target. The four vampires ran south toward the unfinished Washington Monument, into the field of grazing cattle that surrounded it. Construction of the massive marble obelisk (at 150 feet, it was only one-third its eventual height) had been halted, and a temporary slaughterhouse erected in its shadow to help meet the needs of a hungry army. It was into this long, wooden building that the stranger now disappeared, desperate to lose the killers who were only fifty yards behind him. Perhaps there would be knives to fight with inside… blood to throw them off his scent… anything .

But there were no carcasses in the slaughterhouse that Sunday afternoon. No workers cutting the throats of cattle. Only dozens of metal hooks hanging from rafters overhead, each reflecting the late-day sun that squeezed through the open doors at both ends of the long building. The stranger ran across the bloodstained wooden floor looking for a place to hide, a weapon to wield. He found neither.

The river … I can lose them in the river …

He sprinted toward an open door at the far end, determined to head south to the Potomac. Once there, he would dive beneath its surface and slip away. But his exit was blocked by the silhouette of a man.

The other door …

The stranger stopped and turned back—there were two more silhouettes behind him.

There would be no escape.

He stood near the center of the long building as his pursuers advanced from either end, slowly, cautiously. They meant to capture him. Torture him. Demand to know who’d sent him, and what he’d done to the boy. And, if captured, chances were that he would tell them everything. This he could not allow.

The stranger smiled as his pursuers neared. “Know this,” he said. “That you are the slaves of slaves.” He took a breath, closed his eyes, and leapt onto one of the hanging hooks, stabbing himself through the heart.

Читать дальше