Уильям Шекспир - Othello

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Уильям Шекспир - Othello» — ознакомительный отрывок электронной книги совершенно бесплатно, а после прочтения отрывка купить полную версию. В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Жанр: Старинная литература, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Othello

- Автор:

- Жанр:

- Год:неизвестен

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:4 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Othello: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Othello»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

Othello — читать онлайн ознакомительный отрывок

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Othello», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

ACT 5 SCENE 2 Lines 1–123:Othello approaches Desdemona’s bed, holding a light—a visual symbol of the light/life, darkness/death imagery that runs throughout his soliloquy. He dwells on images of purity, such as alabaster and snow, and images of death, many of which have a sexual connotation, such as the plucked rose. He kisses Desdemona and his resolve almost breaks. She wakes and he tells her that she must pray, as he cannot kill her “unpreparèd spirit.” Desdemona pleads with Othello, repeating that she does not love Cassio and did not give him the handkerchief. Othello informs her that Cassio is dead and, misunderstanding her innocent tears at this news, he smothers her. As he does so, Emilia calls for him. His calm certainty breaks down as he fluctuates between Emilia’s calls and Desdemona’s body. Eventually, he lets Emilia in.

Lines 124–270:Emilia reports that Cassio has killed Rodorigo, and Othello is dismayed to learn that Cassio is not dead. As they talk, Desdemona cries out, and, parting the bed curtains, Emilia finds her. Desdemona claims that she is “guiltless” and, denying Othello’s responsibility for her murder, she dies. Othello, however, sees Desdemona’s final act as further evidence that Desdemona is “a liar gone to burning hell” and tells Emilia that he killed his wife because “she was a whore.” Emilia argues that Desdemona was “heavenly true” and Othello tells her that her own husband told him of Desdemona’s affair with Cassio. Emilia is stunned and unable to say anything except “My husband?” for some time, before scornfully telling Othello that Iago lied and that he is a “gull.” She calls for help. Montano, Gratiano, and Iago enter, and Emilia tells Iago that he “told a lie, an odious, damnèd lie,” a sharp contrast to the label of honesty he has been given throughout the play. She announces that Desdemona is dead and Gratiano and Montano are horrified. Gratiano reveals that Brabantio has died in grief at his daughter’s marriage. Othello insists that Desdemona was “foul” and unfaithful, and tells them that she gave Cassio the handkerchief. Despite Iago’s threats, Emilia bravely reveals that she found the handkerchief and gave it to him. Othello tries to kill Iago, but Iago stabs Emilia and flees.

Lines 271–416:Emilia asks to be laid by her mistress’s side. Montano tells Gratiano to guard “the Moor” while he pursues Iago. Emilia’s last words are to assure Othello of Desdemona’s innocence and her love for him. As Othello laments Desdemona’s death, Lodovico and Montano bring in Iago as a prisoner and the wounded Cassio. Othello stabs Iago but fails to kill him. With all the remaining characters assembled, the truth is established and evidence produced of Iago’s villainy, but he refuses to explain himself and vows “From this time forth I never will speak word.” Othello is stripped of his command and Cassio given leadership in Cyprus. As he is to be led away, Othello begs to be remembered as “one that loved not wisely but too well” before stabbing himself. He kisses Desdemona as he dies. Iago’s punishment is for Cassio to decide. Lodovico recommends the use of torture while he returns immediately to Venice to report what has happened.

OTHELLO IN PERFORMANCE: THE RSC AND BEYONDThe best way to understand a Shakespeare play is to see it or ideally to participate in it. By examining a range of productions, we may gain a sense of the extraordinary variety of approaches and interpretations that are possible—a variety that gives Shakespeare his unique capacity to be reinvented and made “our contemporary” four centuries after his death.We begin with a brief overview of the play’s theatrical and cinematic life, offering historical perspectives on how it has been performed. We then analyze in more detail a series of productions staged over the last half-century by the Royal Shakespeare Company. The sense of dialogue between productions that can only occur when a company is dedicated to the revival and investigation of the Shakespeare canon over a long period, together with the uniquely comprehensive archival resource of promptbooks, program notes, reviews, and interviews held on behalf of the RSC at the Shakespeare Birthplace Trust in Stratford-upon-Avon, allows an “RSC stage history” to become a crucible in which the chemistry of the play can be explored.Finally, we go to the horse’s mouth. Modern theater is dominated by the figure of the director. He or she must hold together the whole play, whereas the actor must concentrate on his or her part. The director’s viewpoint is therefore especially valuable. Shakespeare’s plasticity is wonderfully revealed when we hear directors of highly successful productions answering the same questions in very different ways.

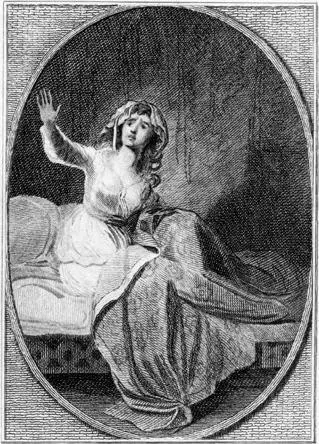

FOUR CENTURIES OF OTHELLO : AN OVERVIEWDespite the theatrical challenges it presents, Othello has been performed almost continuously since the first recorded performance on November 1, 1604, at the court of James I. This has resulted in a remarkably full performance history focused historically on the roles of Othello and Iago and, to a lesser extent, Desdemona. The uneven balance between the main parts, with Iago speaking 31 percent of the lines to Othello’s 25 percent, has often resulted in a sort of theatrical contest between the two which a number of productions have capitalized on by having actors alternate the roles.Richard Burbage, the leading tragedian with the King’s Men, and the first Othello, was celebrated for his performance, described by an anonymous elegist as “his chiefest part, / Wherein beyond the rest he moved the heart.” There is evidence that Iago was played by one of the company comedians, John Lowin. 1A spectator of the performance by the King’s Men at Oxford in 1610 records how the audience was moved “to tears” in the last scene when “that famous Desdemona, killed before us by her husband, although she always acted her whole part supremely well, when she was killed she was even more moving, for when she fell back upon the bed she implored the pity of the spectators by her very face.” 2Interestingly, neither Othello’s color nor the fact that Desdemona was played by a boy was considered noteworthy. After Burbage’s death, until the closure of the theaters in 1642 Othello was played by Ellyaerdt Swanston with Joseph Taylor as Iago. Since Taylor is also known to have inherited the role of Hamlet, this suggests that it was no longer regarded as a role for a comic actor. Othello was one of the first plays to be performed after the Restoration and subsequent reopening of the theaters in 1660. It was assigned to the newly formed King’s Men under Thomas Killigrew and hence avoided the radical rewriting of William Davenant, although promptbooks that survive for the next two centuries record a tendency to cut lines and sometimes whole scenes (such as Othello’s fit and the eavesdropping scene) that came to be regarded as lacking in decorum. 3Samuel Pepys saw a performance at the Phoenix, recording in his diary how the “very pretty lady that sat by me cried to see Desdemona smothered.” 4The Restoration theater introduced scenery and women actors, but the first recorded instance of a woman performing on the English stage was Margaret Hughes as Desdemona on December 8, 1660, so the production Pepys saw in October which so moved the “pretty lady” must have been with a boy actor.Othello was the part in which Thomas Betterton, the leading actor of the early eighteenth century, “excelled himself,” according to Colley Cibber. 5Judging by contemporary accounts, he was able to combine heroic and pathetic aspects of the character. Cibber talks of Betterton’s “commanding mien of majesty” and the way in which his voice “gave more spirit to terror than the softer passions,” whereas Richard Steele was struck by “the wonderful agony” in which he appeared “when he examined the circumstances of the handkerchief…the mixture of love that intruded upon his mind upon the innocent answers Desdemona makes.” 6If Othello was the noble Moor, Iago had to be irredeemably villainous; the actor specializing in such parts who played Iago to Betterton’s Othello was Samuel Sandford, described by Cibber as “a low and crooked person” having “such bodily defects” as rendered him unsuitable for “great or amiable characters.” 7Barton Booth, renowned for noble deportment and dignity, took over the part from Betterton, bringing charm and “manly sweetness” to the role and a grief in which his “tears broke from him.” 8The Grub Street Journal complained that Colley Cibber’s Iago, by contrast,“shrugs up his shoulders, shakes his noddle, and with a fawning motion of his hands” drawls out his words so that “Othello must be supposed a fool, a stock, if he does not see through him.” 9James Quin, who succeeded Booth, was also noted for his dignity, whereas David Garrick, who revolutionized eighteenth-century acting with his ease and naturalness, failed in the part. His interpretation, described as suggesting rather “a man under the impression of fear, or on whom some bodily torture was inflicting, than one labouring under the emotions of such tumultuous passions,” 10was clearly in advance of the times.Contemporary criticism suggests a growing awareness of racial issues. The actor-dramatist Samuel Foote objected to Quin’s performance, commenting: “Sure never has there been a character more generally misunderstood, both by audience and actor, than this before us, to mistake the most tender-hearted, compassionate, humane man, for a cruel, bloody, and obdurate savage,” 11while Quin in turn criticized Garrick’s appearance in the part, for which he wore a turban, asking: “Why does he not bring the tea-kettle and lamp?” 12—a reference to the “small black boy in a plumed turban holding a kettle in Hogarth’s series A Harlot’s Progress .” 13Garrick was more successful as one of several actors who played Iago to Spranger Barry’s handsome, graceful Othello. Barry contrived by all accounts to be even more “sweet” and “comely” 14than Booth. His performance, characterized by “blended passages of rage and heartfelt affection ,” 15was perfectly matched by Susanna Cibber’s “expression of love, grief, tenderness” 16as Desdemona.A translation of the play in 1792 by Jean-François Ducis, in which the great French tragedian Talma played Othello, caught the mood of revolutionary France, coming a year after the successful slave revolt in the French colony of San Domingo (modern-day Haiti). Ducis’ version was heavily cut and adapted. There was further cutting of the English text in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries in the interests of propriety, which suited the neoclassical acting of John Philip Kemble, described by Hazlitt as “the very still-life and statuary of the stage.” 17His Othello was “grand and awful and pathetic,…European,” 18despite his Moorish costume. However, Kemble’s sister, Sarah Siddons, playing Desdemona, was warmly praised and given credit for a changed appreciation of the role in which she “established an interest and importance to that character which it had never possessed before.” 19Despite the beginnings of a changing critical perspective with regard to Iago, the part was still being played as “a pantomime villain,” 20although Edmund Kean had given an innovative performance as “a gay, light-hearted monster, a careless, cordial, comfortable villain.” 21Kean went on to play Othello for many years in a performance Leigh Hunt regarded as “the masterpiece of the living stage.” 22Like Garrick before him, Kean brought passion and naturalism to his roles, triumphing as Othello despite the limitations imposed by his physique. 23He used relatively light makeup for the part in order for his facial expressions to be more easily visible. Kean’s performance developed over the years and he continued to play the part until 1833, when he finally collapsed onstage into the arms of his son Charles, who was then playing Iago. By the time that William Charles Macready took over the role, there was a growing public debate over Othello’s racial origins and the role of sexuality within the play. Macready had played Iago to Kean’s Othello, but was “baffled” 24when he took over the role.  2. “Talk you of killing?” Sarah Siddons as Desdemona at Drury Lane in 1785. Her performance established a new “interest and importance” to the part.

2. “Talk you of killing?” Sarah Siddons as Desdemona at Drury Lane in 1785. Her performance established a new “interest and importance” to the part.

Интервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Othello»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Othello» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Othello» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.