In the corner of the visitors’ room was a slender, handsome man with wire-rimmed glasses and a navy-blue artist’s smock over a T-shirt that said “University of Wisconsin.” He was holding a book and looked like an American student abroad, and it took me a moment to realize that I was staring at Krystian Bala. “I’m glad you could come,” he said as he shook my hand, leading me to one of the tables. “This whole thing is farce, like something out of Kafka.” He spoke clear English but with a heavy accent, so that his “s”es sounded like “z”s.

Sitting down, he leaned across the table, and I could see that his cheeks were drawn, he had dark circles around his eyes, and his curly hair was standing up in front, as if he had been anxiously running his fingers through it. “I am being sentenced to prison for twenty-five years for writing a book—a book!” he said. “It is ridiculous. It is bullshit. Excuse my language, but that is what it is. Look, I wrote a novel, a crazy novel. Is the book vulgar? Yes. Is it obscene? Yes. Is it bawdy? Yes. Is it offensive? Yes. I intended it to be. This was a work of provocation.” He paused, searching for an example, then added, “I wrote, for instance, that it would be easier for Christ to come out of a woman’s womb than for me—” He stopped, catching himself. “I mean, for the narrator to fuck her. You see, this is supposed to offend.” He went on, “What is happening to me is like what happened to Salman Rushdie.”

As he spoke, he placed the book that he was carrying on the table. It was a worn, battered copy of “Amok.” When I asked Bala about the evidence against him, such as the cell phone and the calling card, he sounded evasive and, at times, conspiratorial. “The calling card is not mine,” he said. “Someone is trying to set me up. I don’t know who yet, but someone is out to destroy me.” His hand touched mine. “Don’t you see what they are doing? They are constructing this reality and forcing me to live inside it.”

He said that he had filed an appeal, which cited logical and factual inconsistencies in the trial. For instance, one medical examiner said that Janiszewski had drowned, whereas another insisted that he had died of strangulation. The judge herself had admitted that she was not sure if Bala had carried out the crime alone or with an accomplice.

When I asked him about “Amok,” Bala became animated and gave direct and detailed answers. “The thesis of the book is not my personal thesis,” he said. “I’m not an anti-feminist. I’m not a chauvinist. I’m not heartless. Chris, in many places, is my anti-hero.” Several times, he pointed to my pad and said, “Put this down” or “This is important.” As he watched me taking notes, he said, with a hint of awe, “You see how crazy this is? You are here writing a story about a story I made up about a murder that never happened.” On virtually every page of his copy of “Amok,” he had underlined passages and scribbled notations in the margins. Later, he showed me several scraps of paper on which he had drawn elaborate diagrams revealing his literary influences. It was clear that, in prison, he had become even more consumed by the book. “I sometimes read pages aloud to my cellmates,” he said.

One question that was never answered at the trial still hovered over the case: Why would someone commit a murder and then write about it in a novel that would help to get him caught? In “Crime and Punishment,” Raskolnikov speculates that even the smartest criminal makes mistakes, because he “experiences at the moment of the crime a sort of failure of will and reason, which … are replaced by a phenomenal, childish thoughtlessness, just at the moment when reason and prudence are most necessary.” “Amok,” however, had been published three years after the murder. If Bala was guilty of murder, the cause was not a “failure of will and reason” but, rather, an excess of both.

Some observers wondered if Bala had wanted to get caught, or, at least, to unburden himself. In “Amok,” Chris speaks of having a “guilty conscience” and of his desire to remove his “white gloves of silence.” Though Bala maintained his innocence, it was possible to read the novel as a kind of confession. Wroblewski and the authorities, who believed that Bala’s greatest desire was to attain literary immortality, saw his crime and his writing as indivisible. At the trial, Janiszewski’s widow pleaded with the press to stop making Bala out to be an artist rather than a murderer. Since his arrest, “Amok” had become a sensation in Poland, selling out at virtually every bookstore.

“There’s going to be a new edition coming out with an afterword about the trial and all the events that have happened,” Bala told me excitedly. “Other countries are interested in publishing it as well.” Flipping through the pages of his own copy, he added, “There’s never been a book quite like this.”

As we spoke, he seemed far less interested in the idea of the “perfect crime” than he was in the “perfect story,” which, in his definition, pushed past the boundaries of aesthetics and reality and morality charted by his literary forebears. “You know, I’m working on a sequel to ‘Amok,’ ” he said, his eyes lighting up. “It’s called ‘De Liryk.’ ” He repeated the words several times. “It’s a pun. It means ‘lyrics,’ as in a story, or ‘delirium.’ ”

He explained that he had started the new book before he was arrested, but that the police had seized his computer, which contained his only copy. (He was trying to get the files back.) The authorities told me that they had found in the computer evidence that Bala was collecting information on Stasia’s new boyfriend, Harry. “Single, 34 years old, his mom died when he was 8,” Bala had written. “Apparently works at the railway company, probably as a train driver but I’m not sure.” Wroblewski and the authorities suspected that Harry might be Bala’s next target. After Bala had learned that Harry visited an Internet chat room, he had posted a message at the site, under an assumed name, saying, “Sorry to bother you but I’m looking for Harry. Does anyone know him from Chojnow?”

Bala told me that he hoped to complete his second novel after the appeals court made its ruling. In fact, several weeks after we spoke, the court, to the disbelief of many, annulled the original verdict. Although the appeals panel found an “undoubted connection” between Bala and the murder, it concluded that there were still gaps in the “logical chain of evidence,” such as the medical examiners’ conflicting testimony, which needed to be resolved. The panel refused to release Bala from prison, but ordered a new trial.

Bala insisted that, no matter what happened, he would finish “De Liryk.” He glanced at the guards, as if afraid they might hear him, then leaned forward and whispered, “This book is going to be even more shocking.”

—February, 2008

In December of 2008, Bala received a new trial. Once more, he was found guilty. He is currently serving a twenty-five-year sentence.

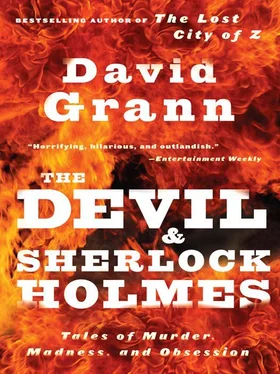

Giving “The Devil” His Due

THE DEATH SQUAD

THE DEATH SQUAD

REAL-ESTATE

AGENT

Читать дальше