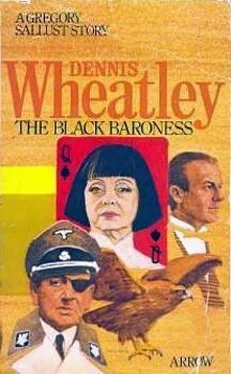

Dennis Wheatley - The Black Baroness

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Dennis Wheatley - The Black Baroness» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Жанр: Старинная литература, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:The Black Baroness

- Автор:

- Жанр:

- Год:неизвестен

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:3 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

The Black Baroness: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «The Black Baroness»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

The Black Baroness — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «The Black Baroness», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

'You adorable swine. Then we can tell her that we know hardly anybody here and suggest throwing a dinner-party to which we'll ask her to bring her friends.'

'I think we should go further than that. I'm certain that Paula is the type who thoroughly enjoys a playful beating, and since I disappointed her by deliberately labelling myself "tame cat" we must arrange for the lady's requirements to be satisfied elsewhere.'

'Stefan!' said Erika.

'Exactly,' grinned Gregory. 'Paula can't be getting much fun with that old Norwegian Major, who is obviously her duty boyfriend at the moment, and Kuporovitch is like a dog with two tails to wag, he's so full of beans after his escape from the Soviets. These Russians have the hell of a reputation with the girls so I don't think Stefan should find much difficulty in making the running. The question is, though, would he be prepared to play a hand with us against the Gestapo?'

'True. He's a neutral, and there's no earthly reason why he should involve himself in our affairs, but I'm sure that we can trust him not to give us away, and he'd be splendid bait for Paula. Let's tackle him this evening and see how far he is prepared to go.'

That night after dinner, in a quiet corner of the lounge, Gregory explained to the Russian the reason why he had cancelled his departure for England at the last moment, and as Paula was really a very attractive young woman he was able to describe her without unduly overpainting the picture, which might have led to Kuporovitch's being disappointed when he later saw her in the flesh.

'She sounds a most delightful person,' the Russian remarked, 'and although my blonde is a nice little thing she is exceedingly stupid so I should much prefer a mistress of my own class. It was most charming of you to think of me, but'—his blue eyes narrowed slightly—'what is the catch in it?'

'There is no catch in it at all,' Gregory assured him. 'If you can get her, Stefan, it will be all for love and should be excellent fun for you, but while we are on the matter I'd like to know what you really feel about the war.'

'What has that to do with it?'

'Just this. We've told you how we met Fraulein von Stein-metz and what she's up to here. Erika and I are two of the considerable number of people in this world who have made up their minds that Hitler has got to be slogged for ten and counted out for keeps, and we don't particularly mind if we lose our own lives in helping along the process. You probably don't feel so strongly that way—or you may even admire the Nazis, for all I know, although I suppose the real fact is that you don't give a hoot for any of us. What I really want to get at is if you would be prepared to pass on to us any information you may be able to get out of Paula should you succeed in making the running with her.'

Kuporovitch showed his even white teeth in a wide smile. 'You are right; I am now a man of no country and no allegiances. My own poor land is ruined beyond repair and I have no interest in Germany or Britain. All the same, I have certain convictions about how people should be governed. I did not like living under an Autocracy where some rascally favourite of the Tsar might say "Off with his head!" about any person he didn't like, at any minute, and promotion could be achieved only by influence or bribery.

Equally, I should not like to live under a Democracy. I despise leaders who are afraid to lead because they must pander to every whim of an ill-informed mob for fear that if they do not they will be thrown out of office at the next election; but even under these two muddle-headed systems something of man's independence and creative spirit is allowed to survive.

'On the other hand, in a Totalitarian state that is not so. People lose all their individuality and become only pieces of the state machine which they are compelled to serve from birth to death. I know that, because I have lived under such a regime for nearly a quarter of a century. There is no more colour in life, no more joy; only one eternal fear of being reported, which forces one to curb every ambition or desire to express oneself and, instead, to take the protective colouring of the great illiterate mass.

'I am an old-fashioned person animated by entirely selfish motives. Quite frankly, I am not in the least interested in the betterment of the masses, but I am extremely interested in gratifying the tastes which I acquired when I was young. I like good food and good wine, beautiful women to make love to, fine horses to ride, freedom to travel and meet many people, music, painting and books which will enable me to explore every type of mind and discuss it without restraint. No Totalitarian world-order would permit me to enjoy more than a fraction of these things—and then only surreptitiously. Since, therefore, this is not a war of nations but a world-wide civil war, I am neither for the British nor for the Germans but I am one hundred per cent against the Nazis.'

'Good man!' cried Gregory. 'We can rely on you, then, to secure all the dope you possibly can through the beautiful Paula?'

Kuporovitch nodded and his lazy blue eyes took on a thoughtful look. 'Leave her to me. Unless I have lost my cunning I have rather a way with young women and, if you have described her type accurately, she will take like a duck to water to some of the little Russian tricks that I can show her. What is it that you particularly want me to find out?'

Gregory's reply came without hesitation. 'The date on which Hitler proposes to invade Norway.'

CHAPTER 3

The Rats of Norway

Paula's French was not excellent but adequate, and love—if you can call it love in such a case—has its own language. At the dinner-party that Erika gave the following night she did not place Kuporovitch next to Paula but next to herself, and she quite obviously cold-shouldered Gregory for him. Erika and Gregory had given out that they had spent the last few months in Finland but nothing had been said of their having been in Russia with Kuporovitch, so the impression was created that he was a new acquaintance who happened to be staying in the same hotel.

When at last, in the lounge afterwards, he did get a word alone with Paula, Erika gave them only a few minutes together, then, feigning ill-concealed jealousy, intervened to reclaim him. Paula was, therefore, all the more tickled the following morning when he rang her up to say that he had succeeded in obtaining her address from one of the other guests at the party and that he was so impatient to see her again that he absolutely demanded that she should lunch with him.

From that point matters developed rapidly. Erika pretended to be peeved and Paula became all the nicer to her as she could not resist the temptation to patronise the lovely rival over whom it had given her such a kick to triumph. In consequence, she showered Erika with gifts and secured invitations for her and Gregory to every party that any member of her set was giving.

Inside a week they knew a hundred people, all of whom appeared entirely unconcerned with the grim struggle that was being waged outside Norway's borders. They lunched and chattered; cocktailed and flirted; dined, danced and drank far into each night. Oslo was throwing off its winter furs and coming out to enjoy the spring sunshine. All Paula's friends seemed to have plenty of money and nearly all of them were indulging in some illicit love-affair which provided gossip and speculation for the rest. It was a grand life for those who liked it, and the Norwegians, who formed far the greatest proportion of the men in this interesting set, were quite obviously having the time of their lives. Norway is not a rich country and her official classes cannot normally afford the same extravagances as their opposite numbers in London, Paris or New York, but Gregory noted with cynical interest that this group of soldiers, politicians, diplomats and Civil Servants always had ample funds and nice new cars in which to take their little German girl-friends about.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «The Black Baroness»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «The Black Baroness» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «The Black Baroness» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.