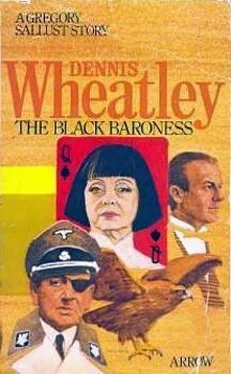

Dennis Wheatley - The Black Baroness

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Dennis Wheatley - The Black Baroness» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Жанр: Старинная литература, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:The Black Baroness

- Автор:

- Жанр:

- Год:неизвестен

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:3 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

The Black Baroness: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «The Black Baroness»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

The Black Baroness — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «The Black Baroness», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

The Major showed no surprise at Gregory's presence, as they had met casually at two or three parties, and since he was posing as a German Staff-Colonel there was nothing surprising about his having accompanied the German Air Attache upon this unusual occasion. Having closed the door behind him, Heering shot a nervous glance at von Ziegler and said:

'You may have to wait some time; the whole place has been in a pandemonium ever since the guns opened at four o'clock this morning. I've been trying to get him on his own for the last quarter of an hour but it's next to impossible.'

'You'll have to manage it somehow,' replied von Ziegler with brusque authority, and Gregory noted grimly that now that the German troops were in the country their representative no longer troubled to conceal the iron hand beneath the velvet glove; things were obviously going to go badly for the red-faced Norwegian if he failed to fulfil the German Air Attache's wishes.

'I've been doing my best,' protested the Major huffily.

'Then you must do better, my friend,' was the smooth reply.

'All right. Wait here; but you must be patient, otherwise we may ruin the whole thing.' The flustered Major disappeared.

Gregory prayed that the Major might still find it impossible to get a word alone with the King for a considerable time to come, since if they were detained long enough in the waiting-room it might give him just a chance to pull a fast one over the German.

He was a little chary of discussing the invasion, as in his role of a German staff-officer he would naturally be expected to know the main outlines of the operation and if he slipped up and showed ignorance upon any essential point in the plan he would immediately arouse von Zieglers' suspicions, but he began to talk of Norway in a general way and of the benefits that Germany would derive from its occupation.

Von Ziegler agreed that it was a clever stroke as, apart from the produce that could be looted from the country, it would give them many hundreds of miles of tortuous sea-coast where submarine bases could be established for attacks on Britain. 'Of course,' he added with a laugh, 'the whole thing would have been impossible if the British had proper leaders. One must not underrate them as a people, because they're tough as blazes when it comes to a real show-down, but the old gentlemen who are running the country now have simply played into our hands. If they hadn't been dead from the neck up we should never have been able to land our troops in Bergen, Trondheim and Narvik.'

It was all Gregory could do to suppress an exclamation of astonishment and fury. He could hardly believe that the Germans had been allowed to land as far north as Trondheim—let alone Narvik—without any attempt being made to intercept them, but he knew that von Ziegler would never have made such a statement if it were not true. However, the German went on in a way which revealed that the Nazis had had their men hidden in barges and other vessels all ready to come ashore in these ports, which to some extent explained what had happened. Naturally, the British could not have known that they would do that, so they had had no chance to sink these Nazi contingents before they reached their destination. Evidently it was the Intelligence, and not the Navy, who were to blame, and Gregory endeavoured to comfort himself with the thought that in this way the Germans could not have landed any considerable forces with tanks and modern war equipment. They would be unable to reinforce their landing-parties and when the British arrived they would mop them up at their leisure.

As they talked Gregory kept his eye on the clock and as the minute-hand circled the dial his hopes gradually rose. When it touched half-past ten they had been in the Palace for over an hour, so he felt that he might attempt to put his wild scheme into operation with a reasonable chance that von Ziegler would not suspect what he was up to.

First he began to fidget, then he stood up and started to pace up and down. Von Ziegler glanced at him after a few moments and murmured: 'What's the matter?'

Gregory walked over and pressed the bell as he replied: 'I've been on the go ever since one o'clock this morning so I'm going to leave you for a moment.'

In response to his ring the liveried footman appeared and Gregory, guessing that all the Palace servants would understand German, said quietly: 'Show me the way to the toilet, will you?' Then he walked calmly out of the room with the man behind him.

While it had appeared that at any moment they were about to arrest the King he had not dared to pull that old bluff to get a few moments out of sight and earshot of von Ziegler; but once it seemed that their time of waiting had become indefinite his decision to absent himself temporarily could not be taken as unnatural. Everything hung upon von Ziegler's remaining unsuspicious of him, and it was for that reason that he had felt it absolutely vital to remain there talking for so long before playing this risky card.

Even now it was only a long shot that his plan would come off, but it was better to try it than to do nothing. He allowed the footman to lead him down a long corridor and when the man threw open the door of a tiled wash-room he turned and faced him.

'How d'you feel about this morning's events?' he asked tonelessly.

The man remained standing in the half-open doorway and looked uncomfortably at his feet. 'Your soldiers are killing my countrymen down at the docks, sir,' he muttered. 'You cannot expect me to feel happy about that.'

Gregory's face twisted into an ugly sneer. 'If they are fools enough to resist, that is their own fault. But they won't resist for long; you Norwegians are too soft and pampered for that; it's time you had a lesson.'

The footman suddenly looked up and his brown eyes were flashing. 'You're wrong there; my people are a hardy folk. You wait until you get up into the mountains—some of us Norwegians will teach you lousy Nazis a thing or two then!'

Gregory's face suddenly relaxed into a smile. Producing his 'last Will and Testament' he held it out to the astonished footman and said: 'You're a loyal Norwegian—thank God for that! Now listen. The King is in the utmost danger. Never mind who I am or how I know. Never mind about etiquette—if necessary, push past anybody who tries to stop you—but you've got to go upstairs at once and give this piece of paper into the King's own hand. If you can do that you will have the right to be the proudest man in Norway, because you will have saved your King from being kidnapped by the Nazis.'

His tone was so earnest that it never even occurred to the man to doubt him. With a swift nod he took the paper and put it in his pocket. 'Very well, sir; I'll do that. It was lucky, though, that you spoke to me and not some of these chaps in service at the Palace—half of them have gone pro-Hitler.'

Two minutes later Gregory was back with von Ziegler and he sat down to await the outcome of his plan.

Knowing that the King spoke English, he had written his 'Will' in that language and it read:

Get out—get out—get out—instantly! Your guards have arranged to betray you to the enemy and German officers are already waiting downstairs to arrest you. Tear off the bottom strip of this paper and leave by one of the back entrances to the Palace. If anyone tries to stop you, present the slip and it may get you through. I urge Your Majesty not to lose a moment.

Then, underneath, he had written another three lines in German, French and English, each of which ran: TO WHOM IT MAY CONCERN. New factors have necessitated a change of plan. It is of the utmost importance that His Majesty should be got away from the Palace as quickly as possible. Your co-operation in this is required most urgently.

Below it, little knowing what he had signed, Captain Kurt von Ziegler had appended his signature.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «The Black Baroness»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «The Black Baroness» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «The Black Baroness» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.