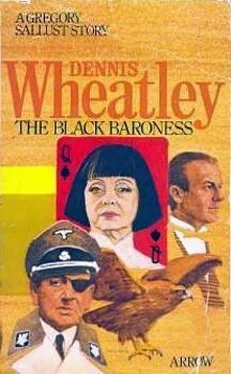

Dennis Wheatley - The Black Baroness

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Dennis Wheatley - The Black Baroness» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Жанр: Старинная литература, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:The Black Baroness

- Автор:

- Жанр:

- Год:неизвестен

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:3 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

The Black Baroness: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «The Black Baroness»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

The Black Baroness — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «The Black Baroness», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

Gregory knew that the Russian had a lion's courage and a serpent's cunning, and that when he said a thing he meant it, so he could not have asked a better protector for Erika. For once he was almost at a loss for words and could only murmur: 'That's good of you, Stefan—damned good of you.'

That week-end of April the 6th and 7th proved a trying one. He was not unduly worried about Erika as, although her change of name was only a comparatively slight protection against her being traced sooner or later by the Gestapo, her new Norwegian nom-de-guerre coupled with her removal to another country would almost certainly secure for her a fresh period of immunity from their unwelcome attentions; but he was restless and uneasy.

He now had many acquaintances in Oslo but that Saturday none of them seemed to be available. They had left the city without warning or were busy arranging to depart on all sorts of different excuses. Even the Norwegian officers whom he had met no longer seemed to have time to spare to amuse themselves; they either had urgent duties or had gone up-country to various military stations, so Gregory decided that zero hour must now be very near.

Having sent to Sir Pellinore all the information that he could secure there was no more that he could do about it, but he was hoping that the Allies would forestall Hitler by a sudden coup. It was common knowledge in Oslo that the Germans had an armada of troopships all ready to sail from their Baltic ports and British Intelligence must be aware of that. In addition, there were his own reports which conveyed the fact that a large section of the ruling caste in Norway had been so seriously undermined that the country would almost certainly capitulate after only a show of resistance. It seemed, therefore, the obvious thing for the Allies to act first and invade Norway before Hitler could get there.

By evening the curious quietness of the city had affected him so strongly that he decided to risk sending an almost open telegram direct to Sir Pellinor. It read: RATS HAVE ALMOST UNDERMINED FOUNDATIONS OF ENTIRE HOUSE STOP SEND

RAT POISON BY AIR AND DISPATCH PESTOLOGIST BY FIRST SHIP STOP MOST

URGENT.

He had no idea what, if any, plans the War Office had made for the invasion of Norway in such an emergency, but he hoped that due notice had been taken of the entirely new tactics which the Germans had used with such success in their conquest of Poland and that the Allies would first seize the Norwegian air-fields then follow up as swiftly as possible with troop-landings.

On the Sunday he spent his time out and about in the city, mixing with the crowd and entering into casual conversation with as many people as possible wherever he found that they could speak English, French or German. He talked to a girl in a tobacconist shop, a professional guide, a taxi-man, several barmen and quite a number of people who were having drinks in bars, and by the end of the day he was beginning to think that he had drawn too black a picture of the situation through having mixed entirely with pro-Nazis during his stay in Oslo.

Quite a large proportion of the ordinary Norwegians were sympathetic to Germany but very few of them were pro-Hitler and none at all thought that it would be a good thing if Norway were incorporated into a German-led federation under him. They had heard too much about the concentration-camps, the forced labour, the suppression of the Press and of free speech, which all went with the Nazi regime, to have the least wish to surrender themselves to it. Their one desire was to preserve their independence and they were prepared to fight for it if they had to; but when Gregory asked why, in that case, they did not take Mr. Churchill's tip and come in with the Allies in defence of their liberties while the going was good they seemed to think that that was a crazy idea, because Germany was so much nearer to them and so much stronger than Britain. Their success in keeping out of every war for the past hundred years had convinced them that if they kept quiet and gave no offence to their powerful neighbour they would be able to keep out of this one, and some of them even showed definite ill-feeling towards Britain for what they considered her unreasonable attitude in making it difficult for them to maintain good relations with Germany.

In reconsidering the whole situation that evening Gregory came to the conclusion that the Norwegians would fight if they were given a chance, but he was extremely dubious as to what sort of show they would be able to put up in view of his private knowledge that so many of their leaders had already succumbed to Hitler's secret weapon.

On the Monday the quiet tension of the city suddenly gave way to intense excitement. The British Navy had appeared in force off certain points along the coast and was laying minefields in Norwegian territorial waters. The official reason given for this was that the Allies had at last decided to take a strong line and close the winter route by which Germany secured her supplies of iron ore from Narvik.

With huge satisfaction Gregory bought himself a bottle of champagne and sat down to drink it. He was a clever fellow— a monstrous clever fellow—and he was used to reading the news which lies behind the headlines; the story about blocking the iron-ore route was all 'my eye and Betty Martin'. Now that spring was here and the Baltic open again the Nazis could get all the iron ore they wanted without bringing it down the coast of Norway, so why should the Allies suddenly decide to block the winter route of the iron-ore ships when they had left it open until summer was almost here? The thing did not make sense, but was perfectly obvious to anyone. The Navy was really laying minefields to protect lanes through which troopships, bearing the British Army, could come to take over the country. Good old Winston had managed to kick some of his colleagues in the pants and Britain was at last stepping out to fight a war.

Having finished his bottle he went out to the Oslo air-port confidently expecting to see the R.A.F. sail in.

There might be a little mild fighting but he doubted if the Norwegians would put up any serious resistance and thought that if he could establish contact with the British landing-force he might prove useful to them as he now had a thorough knowledge of Oslo and its environs.

Although he waited there until an hour after sunset the British planes did not appear, so he assumed that they meant to make an early-morning landing on the following day, at the same time as the troopships appeared off the Norwegian coast. Back at his hotel he found plenty of people who were only too ready to air their views over rounds of drinks in the bar, and through them he learnt that the Norwegian Press had suddenly turned intensely anti-British. In spite of the number of their ships that had been torpedoed by the Germans they appeared to resent most strongly any suggestion that the British should protect them from the people who were murdering their sailors. Then a Norwegian naval officer came in with the startling news that German battle cruisers and destroyers convoying over one hundred troop and supply ships were reported to have left their ports.

Gregory promptly ordered another bottle of champagne. Such tidings were all that was needed to crown his happiness. The British Fleet was also either in or approaching Norwegian waters. They would catch the Germans and there would be a lovely battle in which they, with their superior numbers, would put paid to Germany's capital ships and sink or capture those hundred transports. Allied transports and aircraft carriers were evidently lying out at sea, just out of sight of the Norwegian coast. The intention was to let the Germans make the first open act of war against Norway so that world opinion and the Norwegian public should quite definitely be swayed on to the Allied side. The Germans were to be given a chance to land a few hundred men, then the balloon would go up; the Navy would sail in and shell their ships to blazes while British forces landed farther up the coast.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «The Black Baroness»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «The Black Baroness» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «The Black Baroness» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.