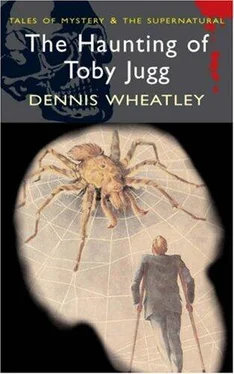

Dennis Wheatley - The Haunting of Toby Jugg

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Dennis Wheatley - The Haunting of Toby Jugg» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Жанр: Старинная литература, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:The Haunting of Toby Jugg

- Автор:

- Жанр:

- Год:неизвестен

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:3 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

The Haunting of Toby Jugg: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «The Haunting of Toby Jugg»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

The Haunting of Toby Jugg — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «The Haunting of Toby Jugg», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

These horrible suspicions about a man for whom, even if he has failed to inspire in me any deep affection, I have always thought of with respect, and regarded as a friend, are enough to make anyone think that I am suffering from persecution mania. But I am sure that I am not. Now that this business of the letters has opened my eyes, I am beginning to see clearly for the first time. There are so many little things for which I have accepted Helmuth's glib explanations, that, looked at now from the new angle, go to show that he not only knows what it is I fear, but is getting some horrible, unnatural kick out of doing all he can to deprive me of protection from it.

To start with, there is the question of the blackout curtain. It was little enough to ask that it should be lengthened by six inches, but he first postponed the issue, then vetoed it entirely.

Then there is my reading lamp. When Deb settles me down for the night she always moved it on to the centre table. After I had the horrors on April the 30th, I asked her to leave it by my bedside, so that I could light it again and read if I felt restless, although, of course, what I really wanted it there for was to light and drown the moonlight if the Thing came again. But she refused. She said that she had had strict instructions from Helmuth that in no circumstances was the Aladdin ever to be left within my reach; because if I read late at nights I might drop asleep while reading, then if I flung out an arm in my sleep I might knock it over, the flaming oil would set the place alight, and I should probably be burnt alive in my bed before anyone could reach me.

That sounds reasonable enough, but, all the same, I tackled him about it. He said he was sorry, but while he was responsible for me he really could not allow me to run such a risk. I asked him, then, to get me an electric torch. He said he would; but next day he volunteered the information that there was none to be had in the village, as all available supplies were now being sent to London and other big cities, where the need for them was more urgent owing to air raids.

That sounds plausible too; but all these things add up, if one starts with the assumption that Helmuth's object is to ensure that at night I should remain a prisoner in the dark apart from that infernal strip of light thrown by the moon and to keep me isolated here. Which reminds me about the telephone.

The main line goes to Helmuth's office, and there are extensions to a few of the bedrooms, up to which, of course, I cannot get. The only other is here, in the library, and I thought that another point in favour of its having been turned into a bed-sit for me. But a few days before I had my first 'nightmare' it went wrong. I asked Helmuth to get it put right, and he said he would; but nothing was done about it. When I spoke to him again he said that he was awfully sorry, but he had heard from the Post Office engineers, and they were so terribly busy installing lines to camps and airfields that they could not possibly find the time to repair extensions in private houses.

He went on to point out that in the three weeks I had been here I hadn't used it more than half a dozen times, so I should hardly miss it; and that if I did want to telephone I could always do so in the daytime by being wheeled along in my chair to his office.

That is all very well, but when Helmuth is not in his office he always keeps it locked. The tacit assumption is, of course, that I have no secrets from him, so there is nothing that I should want to telephone about which it would cause me embarrassment to mention in his presence. But with him at my elbow how can I telephone Julia, as I've wanted to a score of times in the past ten days? I mean, I couldn't possibly tell her in front of him the reason why I want her to cancel all her engagements and fag down here to Wales.

Another pointer concerns the radiogram. Mine is a big cabinet affair, that also plays eight gramophone records off without being touched, and it lives on the far side of the fireplace. When things started to happen again at the beginning of this month I asked to have it moved up close to my bed, so that if I was subject to any more of these damnable visitations it would be within easy reach, and I could turn it on. I had small hope that the sound of martial music would scare the Thing off, but I thought it might fortify me and at least make the room seem a little less like a morgue.

Deb objected at once because the cabinet is so heavy that it takes two people to shift it, and would mean an awful performance each night and morning moving it to and from my bedside; or else it would have to remain there permanently, in which case, whichever side I had it, its bulk would prevent her from getting at me from all angles to give me my massage.

I was so set on having it by me that I appealed to Helmuth; but he supported her. He said that it was unreasonable of me to want to put people to so much bother for a sudden whim; and that, in any case, for the sake of my health I needed all the sleep I could get at nights, so he was averse to any innovation which would enable me to lie awake listening to music.

I suppose most people would consider me a pretty wet sort of type for allowing myself to be dictated to like that; but then they don't know Helmuth. He tackles every problem that arises with such cheerful briskness, and his views are always so clear-cut and logical, that it is almost impossible to argue with him. At least, I find it so; but that may be because he became the dominant influence in my life from the time I was thirteen, and years of unquestioning submission to whatever he considered best for me formed a habit of mind that I now find it almost impossible to break.

That is why I kowtowed to his decision that he could not agree to my shifting my quarters; although I am sure that it would not have made the slightest difference if I had gone off the deep end. He would have told me to 'be my age' and have walked out the room; and he knows perfectly well that it is impossible for me to get myself moved without his consent. His attitude in this, more than in anything else, now convinces me that he is deliberately keeping me a prisoner here, because he knows it to be the focal point of my fears, and is deriving a brutal, cynical amusement from watching them develop.

After these two consecutive nights in early April I already had the wind up pretty badly, so I told him that I wasn't sleeping well, and would like to be moved to another room. There are plenty of others in this great barrack of a place, but he brushed the idea aside with reasons against which it seemed childish to argue.

Obviously, for me to be anywhere but on the ground floor would mean that all my meals would have to be brought up to me, and that I should have to be carried up and down stairs every day to go out for my airing and that would be placing much too great a burden on our very limited staff. The rooms in the old part of the Castle have been long untenanted, and are damp and cheerless. That left only the east wing, which contained the suite of reception rooms in which my Great aunt Sarah vegetates, and I could not possibly turn her out after all these years. Here I have a fine big room that gets all the sun and has easy access to the garden; and if I wasn't sleeping well in it there was no reason whatever to suppose that I should sleep better elsewhere. What could I reply to that? And, as my 'nightmares' did not recur for over three weeks, it was not until the end of the month that I had cause really to worry about the matter further.

But on May the 2nd, after two more visitations, I was in a real flap, and I tackled him again. I said that I had come to the conclusion that Wales did not suit me, and I felt sure that a change of surroundings would do me good.

He dismissed that one as too silly for serious consideration; and I must admit that so long as Britain remains at death grips with Germany we could hardly be better situated than we are down here. It is a far cry from Whitehall to this lonely valley in the heart of the Welsh mountains, and things like rations, Home Guards, A.R.P. and Flag days, seem to belong to a different world. In fact, if it weren't for the blackout, and the odd German bomber that has got off her course passing over us at night once in a while, we might regard the war as though it was taking place on Mars.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «The Haunting of Toby Jugg»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «The Haunting of Toby Jugg» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «The Haunting of Toby Jugg» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.