The dream of Wide which had slipped away from me in Warminster came back to me now we were on the road again. Every day as we went eastward into Hampshire and then towards Sussex it grew stronger. I used to close my eyes every night and know that I would see on my eyelids a high horizon of green hills, a lane white with chalky mud, a straggle of cottages down one main lane. A vicarage opposite a church, a shoulder of bracken-strewn brown common reaching up behind the cottages and a blue sky overarching it all.

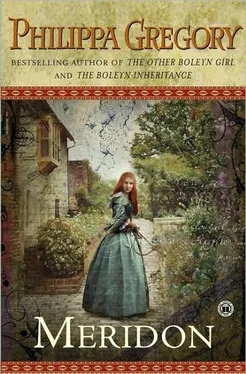

I would dream that I was a girl just like myself, with a tumble of copper hair and green eyes and a great passion for things she could scarcely hope to have. Once I dreamed of her lying with a dark-haired lad and I woke aching with a desire which I had never felt in real life. Once I awoke with a shriek for I dreamed that she had ordered her father’s death and had held the great wooden door open and stared stony-faced as they carried him past her on a hurdle with his head stove in. Dandy had shaken me awake and asked me what was wrong and then hugged me and shielded me from Katie when I told her I had dreamed of Wide, and something awful. That I must stop her, the girl who was me. That I must run to her and warn her against the death of her father.

Dandy had rocked me and held me in her arms as if I were a baby and told me that Wide was a place we had none of us seen, nor heard of. That the girl was not me. That I was Meridon, Meridon the gypsy, the horse-trainer, the showgirl. And then I cried again and would not tell her why. But it was because the gulf between me and the girl in the dream was unbridgeable.

I had another dream too. Not one which woke me screaming, but one which made me long with a great loneliness for the mother that Dandy and I had lost so young. I had somehow got her muddled in my mind with the story Jack had told us of the loss of his mother – of her calling and calling as the wagon went away from her down the road. I certainly knew that my mother had not run after any wagon. She was too ill, poor woman, to run after anything. The memories I had of her were of her lying in the bunk with her mass of black hair, Dandy’s thick black hair, spread out on the pillow all around her, saying to Da in an anxious, fretting voice, ‘You will burn everything when I die, won’t you? Everything. All my dresses and all my goods? It is the way of my people. I need to know you will burn everything.’

He had promised yes. But she had known, and he had known, and even little Dandy and I had known that he would not complete the ceremonies and bury her as a Romany woman should be treated. He took her body off on a handcart and tossed it in the open hole which served as a pauper’s grave. Then he sold her clothes, he did not burn them as he promised. He burned a few rags in an awkward shame-faced way, just things he could not sell. And he tried to tell Dandy and me, who were watching him wide-eyed, that he was keeping his promise to our dead mother. He was a liar through and through. The only promise he kept was to give me my string and gold clasps. And he would have had that off me if he could.

But it was not that death that I remembered. That was not the mother I grieved for in my dream. I dreamed of a thunderstorm, high overhead, a night when no one who could close shutters would venture out. But out in the wind and the rain was a woman. The rain was sluicing down on her head, her feet were cut in many places from the sharp flints in the chalk soil and she limped like a beggar come new to the trade. The pain in her feet was very bad. But she was crying not for that pain but because she had a baby under her arm and she was taking it to the river to throw it away like an in-bred whelp which should be drowned. But the little baby was so warm beneath her arm, hidden from the storm by her cape. And she loved it so dearly she did not know how she could let it go, into the cold water, away into the flood. As she stumbled and sobbed she could feel it nuzzling gently into her armpit, trustingly.

Then the dream melted as dreams will and suddenly there was a wagon, like the one I live in now, like all the wagons I have lived in all my life. And a woman leaning down from the scat by the driver and reaching out for the baby, and taking the baby without a word.

And then – and this is the moment where I suppose the dreams become muddled with Robert Gower’s wife calling after him on the road – then the wagon moved off and the woman was left behind. In one part of her heart she was glad that the child was sent away, off the land, away from her home. And in another part she longed for her child with such a passion that she could not stop herself from running, running on her bleeding feet after the rocking wagon, and calling out, though the wind ripped her words away: ‘Her name is Sarah! Sarah…’

She called some more, but the wind whipped her words away and the woman on the box did not turn her head. And I awoke, in the early, cold grey light, with tears pouring down my cheeks as if I was grieving for a mother who had loved me and given me away; sent me away because there was no safe place for me in my home.

15

The dreams kept waking me at night, and even when I slept I woke weary. Robert looked at me askance around the stem of his pipe and asked if I were sickening. I said, ‘No,’ but I felt tired to my very bones.

I was sleeping poorly, and we were in counties where they watched for their game and we were eating sparingly. Bread, cheese and bacon; but no rich gamey stews. I was working hard. Harder than I had ever worked for my da. At least my da had taken the odd day, sometimes days at a time, when he had done no work at all, disappearing to drink and gamble, and coming home reeling and worthless. With Robert we worked in a steady rhythm of work and moving, and there was nothing else.

Katie kept going, working and practice, doing her act. But she was ready to drop after the last show of an evening. Especially if we were working in a barn and she was doing three shows a day. She would roll into her bunk as soon as she had stripped her costume off. I often saw the two of them, her and Dandy, sleeping naked under the blankets, with their fine flyers’ cloaks spread out over their bunks, when they had been too weary to fold them and put them in the chest. Dandy was exhausted. She had to order the two of them into the rigging for extra practice when the tricks went badly, she had to watch the act, not just as a performer but as a trainer too. And she had to work and work at her own skill. Long after Katie and Jack had dropped down, cursing with weariness into the nets, Dandy would be up there throwing somersaults to an empty trapeze, falling into the net, and going heel-toe, heel-toe, up the ladder to go through the trick again.

I would be working the horses, or fetching them hay and water for the night, and I would go into the barn when I heard the twang of the catch-net and ask Dandy to leave her practice and come to bed. Sometimes I brought her a cup of mulled ale and she would drop from the net and drink it, sitting on one of the benches.

‘Shouldn’t eat nor drink in the ring,’ she said to me once, her face wreathed in steam from the hot ale.

‘Shouldn’t swear either, and all of us do,’ I replied unrepentant. ‘Now you go to bed, Dandy. We’ve another three shows to do tomorrow, you’ll be tired out.’

She yawned and stretched herself. ‘I will,’ she said. ‘You coming?’

I shook my head, though I ached for sleep. ‘I’ve got to clean the harness,’ I said. ‘It’s getting too dirty. I’ll not be long.’

She went without a backward glance, and when I came to the wagon two hours later she and Katie were fast asleep; Dandy on her back, her hair a rumpled black mass on the pillow.

I crept into my own bunk and gathered the blankets around my shoulders in their comforting warmth. But as soon as I shut my eyes I started dreaming again. I would dream I was the red-headed girl and the land was turning against me. I would watch the fields grow ripe and yet know an absolute fear of loss clutch cold at me. I would dream I was the woman who had been out in the storm and I would ache for the loss of the baby whose name was Sarah. Then I would hear her anguished call, and sometimes I would sit bolt upright in my bed, cracking my forehead on the roof of the wagon, as if I were trying to answer her.

Читать дальше

Конец ознакомительного отрывка

Купить книгу