‘Emily and Gerry are coming along behind us, leading Sea, riding the Havering horse and my bay,’ Will said. ‘You and I have bought a ride with this carter who is taking a load of Irish linen bales to Chichester. He will ride straight past your very doorstep, m’lady.’

‘Money?’ I asked succinctly.

‘Gerry had a handsome sum saved against his wedding day,’ Will said happily. ‘I promised I would repay him when we got to Wideacre, and he split the hoard. I’m so glad you decided to rescue him from his servitude. We’d have been stuck penniless without him.’

I chuckled. ‘Where are they now?’ I asked.

Will nodded behind. ‘Dropped back to rest the horses. The carter has an order to meet in Chichester, he’ll be changing his team as we go. We’ll be home by nightfall.’

I snuggled a little deeper and put my hands behind my head to gaze up at the sky.

‘Then we have nothing to do…’ I said.

‘Nothing,’ Will said sweetly. ‘Except rest, and eat, and drink ale, and talk.’

He shifted round so his arm was behind my head and I was leaning against his shoulder, comfortable and warm. He held the flask of ale to my mouth and I took a gulp, then he stoppered it up and leaned back and sighed.

‘Now,’ he said invitingly. ‘Tell me all about it. I want to hear everything, all the secrets, and all the things you thought about when you were alone. I want to know all about you, and it’s time you told me.’

I hesitated.

‘It’s time I knew,’ he said decisively. ‘You must start from the very beginning. We’ve got a long ride and I’m not at all sleepy. Start from the very beginning and tell me. What’s the very first thing you remember?’

I paused and let my mind seek backwards, down the years, a long way back to the dirty-faced little girl in the top bunk who never heard a kind word from anyone except her sister.

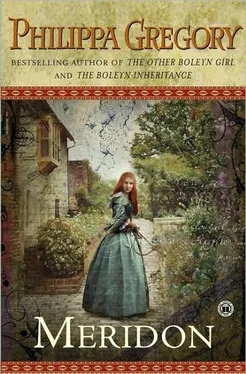

‘Her name was Dandy,’ I said, naming her for the first time in the long sorrowful year since her death. ‘Her name was Dandy, and my name was Meridon.’

I talked as the carter drove. I broke off when we went into inns, and we climbed down from the back and bought the man an ale. He took up another passenger one time, a pretty country girl who sat in the front with him and giggled at the things he said. We sat still and quiet during that time, around noon. But we did not court as they were courting. Will did not kiss me, and I did not box his ears and blush. I rested my head on his shoulder and I felt the tears roll down my cheeks for the two little children in the dirty wagon, and even for Zima’s little babby we had left behind.

When the girl had gone, climbing down at her home, a darkshuttered cottage, leaving with a wave, Will had said softly, ‘You asleep?’ and I had said ‘No.’

‘Tell me then,’ he said. ‘After that first season with Gower, where he took you for winter quarters, tell me about that.’

I thought of the cottage at Warminster, of Mrs Greaves and the skirt which I stained so badly, falling from Sea, that I never had to wear it again. I told him about Dandy and her pink stomacher top and her flying cape, and of David who trained us so kindly and so well.

Then I buried my face in his jacket and told him about the owl which flew into the ring, and about David warning us about the colour green. And how I had forgotten.

I wept then, and Will petted me as if I were a little well-loved child, and wiped my face with his own cotton handkerchief, and made me blow my nose and take a gulp of ale. He took some bread rolls and some cheese from his pocket and we ate them as the sky was growing darker again with the quick cold twilight of winter.

‘And then…’ he prompted, as I finished eating.

I sprawled back against the softness of the straw and turned my face to the sky where the pale stars were starting to show. The evening star hung like a jewel above the dark latticework of the twigs of the passing woods.

My voice was as steady as a ballad singer, but the tears seeped out from my eyelids and rolled down my cheeks in an easy unstoppable flood as if I had waited for a year to cry them away. I told him of Dandy’s plan, and how she trapped Jack. How she teased him and courted him until she had him, and how she got a belly on her which she thought would bring us to a safe haven with the Gowers. That she thought Jack would cleave to her, and that Gower would be glad of a grandson to inherit the show. That she was always a vain silly wench and she never troubled herself to wonder what others might want. She was so anxious to seek and find her own pleasures, she never thought of anyone else.

I should have known.

I should have watched for her.

And I confessed to Will that I had known in some secret shadowy way, I had known all along. I had been haunted. I had seen the owl, I had seen the green ribbons in her hair. But I did not put out my hand to stop her and she went laughing past me, and Jack threw her against the flint wall, and she died.

We were quiet for a long time then. Will said nothing and I was glad of that. It was silent but for the creak, creak noise of the wheels and the steady jolting of the cart, the clip, clop, of the dray horses and the carter’s tuneless whistle. A wood pigeon called for a few drowsy last notes, and then hushed.

‘And then you came to Wideacre,’ Will said.

I turned in his arm and smiled at him. ‘And I met you,’ I said.

He dipped his head down to me and kissed my red swollen eyelids, and my wet cheeks. He kissed my lips which tasted of salt from my tears. He buried his face in my neck and kissed my collar-bone. He reached into my little nest of straw and hidden by my cape his hands stroked me as gentle as a potter moulding clay, as if he were shaping my waist, my breasts, my arms, my throat, my cheekbones. Then his hands slid down over my breasts to the baggy waistband of Gerry’s breeches, and his flat hand stroked down my belly to between my legs.

‘Not now,’ I said. My voice was very low. ‘Not yet.’

He leaned back with a sigh of longing, and pulled my head on to his shoulder. ‘Not long now,’ he said in reply. ‘You’ll come to my cottage tonight.’

I hesitated. ‘I can’t,’ I said. ‘What would Becky say?’

Will looked puzzled for a moment.

‘Becky,’ I said. ‘You told me…that day in the park…you said you were promised to wed her. You said that she loved you. I can’t come to your cottage…I don’t want to spoil things for you…’ I tailed off. I lost my words at the thought of having to share him with another woman. ‘Oh Will…’ I said miserably.

Will Tyacke let out a great guffaw of laughter, so loud that the carter craned around one of the bales to beam at the two of us with his toothless smile.

‘Oh you poor silly darling!’ he exclaimed, and gathered me up into his arms and kissed me hard. ‘You poor silly girl! I told you that in a rage, you simpleton! When you were so full of Lord Perry in your bedroom and his luck at cards! I was angry, I wanted to hurt you back. I’ve not seen hide nor hair of Becky in months! She lived with me while she was ill, and she bedded me then once or twice. Then she worked her way through half the village and when she’d taken her fill of all of us she was up and off to Brighton! We’ve not seen her since.’

‘But her children…?’ I exclaimed. I was stammering with anger. I had pictured her so clearly, and the little faces at the fireside, I had tortured myself to tears thinking of Will beloved in that little family. ‘Will! You lied to me! I broke my heart imagining you and her children all in your cottage together. I have been dreading and dreading the moment you would tell me that you had to stay with her and the children.’

‘Oh I have the children,’ Will said carelessly, and at my astounded look he said: ‘Well, of course I have! She was running around with every man in the village, someone had to look after them! Besides,’ he said reasonably. ‘I love them. When she left, they said they’d like to stay with me. They asked me if I would marry someone so that they might have a new mother.’ He grinned at me sideways. ‘I take it you’ve no objection?’ he asked.

Читать дальше

Конец ознакомительного отрывка

Купить книгу