For my wife, Beverley,

Endlessly patient, long-suffering,

encouraging, supportive, and inspiring

Every Frank feels that once we have reconquered the [Syrian] coast, and the veil of their honor is torn off and destroyed, this country will slip from their grasp, and our hand will reach out towards their own countries.

—Abu Shama, Arab historian,

1203–1267 A.D.

The soldier of Christ kills safely: he dies the more safely. He serves his own interest in dying, and Christ’s interests in killing!

—St. Bernard of Clairvaux,

1090–1153 A.D.

AUTHOR’S NOTE

Where is France? If anyone were to ask you that question casually, you would probably wonder at the ignorance that must obviously underlie it, because you, of course, know exactly where France is, having seen it a thousand times on maps of one kind or another, and it has been there forever, or at least since the last Ice Age came to an end, about ten thousand years ago. So clearly, anyone with a lick of education ought to know where it is without having to ask. And yet, as a writer of historical fiction, I have been having trouble with that question ever since I began to deal with it, because I feel an obligation to maintain a standard of accuracy in the background to my stories, and yet, were I to stick faithfully to the historical sources and absolutes in writing about medieval France, Britain, and Europe, I would be bound to perplex most of my readers, whose simple wish, I believe, is to be amused, entertained, and, one hopes, even fascinated for a few hours while absorbing a reasonably accurate tale about what life was like in other, ancient times.

In writing my Arthurian novels, for example, I was forced to accept and then to demonstrate that the French knight Lancelot du Lac could not have been French in fifth-century, post-Roman Europe, and could not possibly have been called Lancelot du Lac (Lancelot of the Lake) because the country was still called Gaul in those days and the French language, the language of the Franks, was the primitive tongue of the migrating tribes who would one day, hundreds of years in the future, give their name to the territories they conquered.

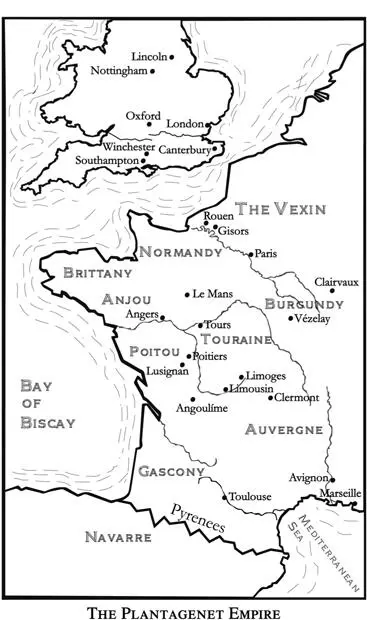

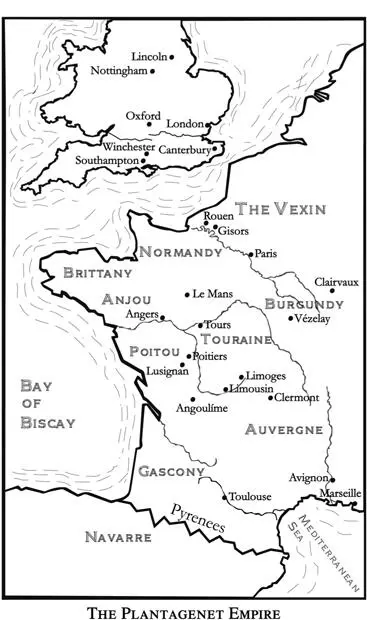

I have had the same difficulty, although admittedly to a lesser degree, in writing this book, because although the country, or more accurately the geographical territory known as France, existed by the twelfth century, it was a far cry from being the France we know today. The Capet family was the royal house of France, but its holdings were still relatively small, and the French king at the time of this story was Philip Augustus. Philip’s kingdom was centered upon Paris and extended westward, in a very narrow belt, to the English Channel, and it had only just begun to develop into the state it would become within the following hundred and fifty years. At the beginning of the twelfth century, it was still tiny, hemmed in by powerful duchies and counties like Burgundy, Anjou, Normandy, Poitou, Aquitaine, Flanders, Brittany, Gascony, and an area called the Vexin, which bordered France’s northern border and would soon be absorbed into the French kingdom. The people of all these territories spoke a common language that would become known as French, but only the people who lived in the actual kingdom of France called themselves Frenchmen. The others took great pride in being Angevins (from Anjou), Poitevins, Normans, Gascons, Bretons, and Burgundians. (Richard Plantagenet, the Duke of Aquitaine and Anjou, in many ways was wealthier and far more potent than the French king. Upon the death of his father, King Henry II, Richard would become King of England, the first of his name, the paladin known as Richard the Lionheart, and he would rule an empire built by his father and his mother, Eleanor of Aquitaine, that was far greater than the territories governed by King Philip.)

To all of us today, they are all Frenchmen, but that was not so in their day, and the task of making that clear to modern readers, demonstrating that those differences existed and were crucially important at times to the people concerned, is the main reason why I often have to ask myself the question I began with here: Where is France?

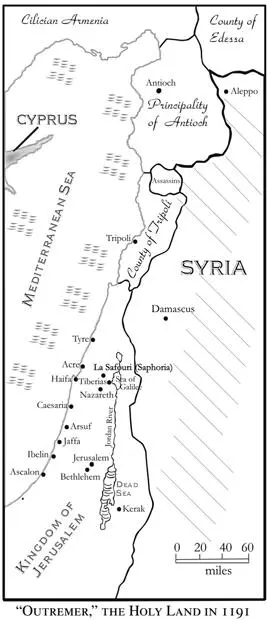

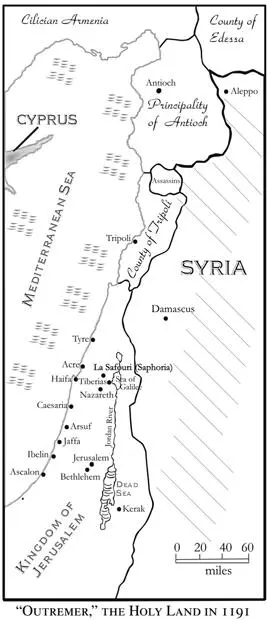

At the time of this story, in the days of Richard Plantagenet and the Third Crusade, the war against the Saracens under the Sultan Saladin, the Knights Templar had not yet achieved the pinnacles of wealth, power, and putative corruption that would so infuriate their contemporaries in later years, engendering envy, malice, and cupidity. But they had nonetheless made unbelievable advances since the time, a mere eighty years earlier, when their membership had numbered nine obscure, penniless knights, living and laboring in the tunnels beneath the Temple Mount in Jerusalem. Within the eight decades since their founding, they had become the standing army of Christianity in Outremer, and their reputation for honor, righteousness, and obedient, unquestioning loyalty to the Catholic Church was sterling and unblemished. From obscurity, the nascent Order had moved directly to celebrity and universal acceptance, and within the same short time, thanks mainly to the enthusiastic and unstinting support of St. Bernard of Clairvaux, the greatest churchman of his day, it had also gone from penury to the possession of incalculable wealth, both in specie and in real property.

From its beginnings, however, the Order had been a secret and secretive society, its rites and ceremonies shrouded in mystery and conducted in darkness, far from the eyes and ears of the uninitiated, and that secrecy, no matter how legitimate its roots might have been, quickly and perhaps inevitably gave rise to the elitism and arrogance that would eventually alienate the rest of the world and contribute greatly to the Order’s downfall.

I suspect that if, after reading this book, you were to go and ask the question of your friends and acquaintances, you might experience some difficulty finding someone who could give you, off the cuff, an accurate and adequate definition of honor. Those who do respond will probably offer synonyms, digging into their memories for other words that are seldom used in today’s world, like integrity, probity, morality, and selfsufficiency based upon an ethical and moral code. Some might even refine that further to include a conscience, but no one has ever really succeeded in defining honor absolutely, because it is a very personal phenomenon, resonating differently in everyone who is aware of it. We seldom speak of it today, in our post-modern, posteverything society. It is an anachronism, a quaint, mildly amusing concept from a bygone time, and those of us who do speak of it and think of it are regarded benevolently, and condescendingly, as eccentrics. But honor, in every age except, perhaps, our own, has been highly regarded and greatly respected, and it has always been one of those intangible attributes that everyone assumes they possess naturally and in abundance. The standards established for it have always been high, and often artificially so, and throughout history battle standards have been waved as symbols of the honor and prowess of their owners. But for men and women of goodwill, the standard of honor has always been individual, jealously guarded, intensely personal, and uncaring of what others may think, say, or do.

Читать дальше

Конец ознакомительного отрывка

Купить книгу