"Dismount, I say, or die." The Legate raised his arm in a signal, and suddenly lines of archers swarmed up the steps and along the platforms on the camp's parapets, where they nocked arrows and aimed at us. Britannicus turned from one side to the other and looked at the archers, and then he eyed the assembled soldiers who hemmed us in. His face was expressionless. Finally, he looked again towards Seneca, in whose face I could see the resemblance to his brother, my former legate in Africa.

"In the absence of criminals, I can only assume that you are addressing me, Legate Seneca?" The expression on Seneca's face was one of triumph.

"I see criminals aplenty, Britannicus. You, and your rabble."

I swung around again to still my men, but there was no need. They were white-faced, most of them, and straining to see over the heads of the men in front of them, but their eyes were on Britannicus, whose voice came again, hard-edged.

"You had better explain that, Seneca."

"There is no need. You and your rabble were convicted as deserters a year ago. No one expected that you would crawl back seeking clemency, but then your character is such that it does not really surprise me."

I could see the tension in every line of Britannicus's being, but his voice remained calm.

"On whose authority was I convicted? And for what cause?"

"For what cause?" Seneca scoffed openly. "For what cause? Is not the loss of a province cause enough? Your incompetence, and that of the others like you, caused the loss of almost the entire land to barbarian invaders, and in recognition of your culpability, you fled the Empire's justice to hide and cower in the hills. Now you have been starved out and come crawling back, hoping for clemency. Enough of this! Order your men to throw down their arms and surrender themselves, or I shall order mine to exterminate them and you."

Britannicus raised his voice. "Flavinius Tesca! Will you come forward, please? And Senator Opius?" There was an uneasy stirring everywhere as all four of the civilians at the back of the ranked soldiers began to move forward. Seneca was not pleased, and was obviously surprised by Britannicus's appeal.

"There is no need for that!" he snapped. "The Senators have no authority here in the field."

The civilians continued to approach, regardless of his words. When they reached the front they stopped, and the tallest of the four nodded to Britannicus, his expression non-committal. Seeing him do so, one of his companions also recognized the Tribune with a tiny nod. Britannicus spoke to the first man.

"Tesca, you are familiar with the situation between my House and the House of Seneca. Am I to be constrained and killed with all my men? For serving the Empire and winning back to civilization? Are we all to stand condemned? By a Seneca? In front of imperial senators?" Tesca looked uncomfortable. "The condemnation is not Seneca's, Caius Britannicus. He is correct. You were convicted in absentia of desertion."

"Why? On whose word?" For the first time, Caius Britannicus allowed his voice to show anger. Tesca shrugged his shoulders. Britannicus kept his voice high, so that everyone in the camp could hear him.

"Flavinius Tesca, I appeal to you as one Roman of senatorial rank to another. Do deserters march into armed camps, under full discipline, to surrender as meekly as we have done? I wish to call one of my men forward. May I do so?"

"No! You may not!" This was Seneca.

Britannicus ignored him. "Senator Tesca? My appeal is to you." Tesca nodded.

"Luscar! Step forward!"

Curullus Luscar, the senior and only surviving clerk of our cohort, marched forward and stood at attention.

"Produce your records, Luscar, and present them to the Senator."

As Luscar complied with the order, my eyes were fastened on Seneca's face, which registered suspicion and puzzlement. Luscar's pack was oversized, but it held few military contents. The entire space within his rigid, thick-sided leather pack was filled with the tightly rolled papyri on which, for the entire duration of our wanderings, he had kept his meticulous record of all our doings, making ink out of soot and urine, and filling the back sides of every document he had carried with his tiny, crabbed scrawl. Britannicus nodded to the piled papyri on the ground.

"I had Luscar keep a record of the events that followed the attack on the Wall last year. Since then, he has recorded everything, writing on the back of his precious records when he ran out of fresh material. He is a scribe by nature and by training, and I see now that God Himself had a hand in keeping him alive.

"I demand that these records be studied. They will attest to the loyalty of every man with me. The loyalty to Rome that brought us safely here after more than a year of struggle." He glared, defiantly, at Tesca, who cleared his throat to indicate his discomfort and then bent to pick up one of the tightly rolled scrolls. No one else moved. After a few moments, Tesca raised his head and cleared his throat again, turning to Seneca for the first time.

"Legate Seneca, the document I have here seems to indicate that an injustice may have been done." He held up his hand to forestall an interruption. "I only say 'may have. ' This is a segment of a military log, dated eight months ago and signed by Tribune Britannicus as officer commanding the cohort."

Seneca was spluttering, his face suffused with anger. "It's a trick, damn you, Tesca! Can't you see that?" Tesca's face became flinty. "No, Legate, I do not see that! What I see seems militarily correct, if highly unusual." He turned and glanced up at Britannicus, and then at the rest of us, before continuing. "I wish to make a strong recommendation. A double recommendation: that the Tribune Britannicus surrender himself and his men, to be kept under guard, until I myself, with my three companions and four of your own officers, have had time to examine these — records — thoroughly."

"Are we yet to be treated, then, as criminals?"

Tesca's eyes went directly to Britannicus, without evasion. "In the eyes of the Empire, you are criminals. I do admit, however, that this —" he indicated the scroll he held, "— this record, as you call it, raises some doubt in my mind. In view of that, if you will consent to simple detention, you will be lodged comfortably, under guard, until we have had time to arrive at a decision, at this level only, regarding your guilt or innocence of the charges under which you stand convicted."

"What then?" Britannicus had lowered his voice again. "You said 'at this level. '"

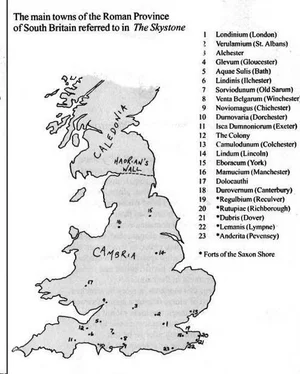

"Then, if we are persuaded of your innocence of the crime of desertion, you will be taken to military headquarters in Lindum to face the Military Governor for formal exoneration."

"All four hundred of us?"

Tesca frowned. "Of course not. You and your officers and your scribe." Britannicus sighed deeply and looked back to the bowmen on the parapets.

"Seneca, " he mused, "your bowmen will have cramps for a week if they do not relax soon."

Seneca, his face suffused with rage and frustration, raised his arm, and I felt my scalp prickle, but he brought it back down slowly and the threatening arrows were lowered. I heard a susurration of released breath from the men behind me.

"That is far more civilized." There was almost a smile in Britannicus's voice. "Flavinius Tesca, I thank you for your level head. Centurion Varrus, pass the word for the men to lay down their weapons and to reassemble... where would you like them to go, Legate, apart from the obvious?"

"Damn you, and them, Britannicus. They'll stay right where they are, at attention."

I didn't move. This was not yet over. Britannicus's voice dropped low, intended for one pair of ears only. "Seneca, my men are hardened. Yours are babies. I will not have my people stand in the sun to soothe your spleen. I will have them assemble outside the gates, and you can mount a guard around them, but by the Living God, if you try to vent your petty anger at me on them, then I'll turn them loose and very few men, yours or mine, will see tomorrow."

Читать дальше