"Well, we will find out early in the proceedings, as soon as we begin to melt it down and turn it into work rods, because we know the number, weight and dimensions of what we require. But by God's bones, we might end up making a scaled-down version, according to what we have to work with. Will that suffice, if it should come to that?"

I shrugged. "I suppose so, but I really can't see that being the case. The statue must be at least three times, perhaps five times or more the weight of Excalibur. I haven't tried to carry it in years, not since I was a boy, but I recall its being very heavy."

"Aye, for a boy." Joseph made a harrumphing sound. "Well, it needs must be twice the weight, at least, for I'll guarantee that half the original weight will be chiseled out and filed away. On the other hand, if you are right and it's five or six times the weight, we may be able to make two of them."

"That would be most unlikely, I should think." I glanced at Ambrose. "What do you think, Ambrose?"

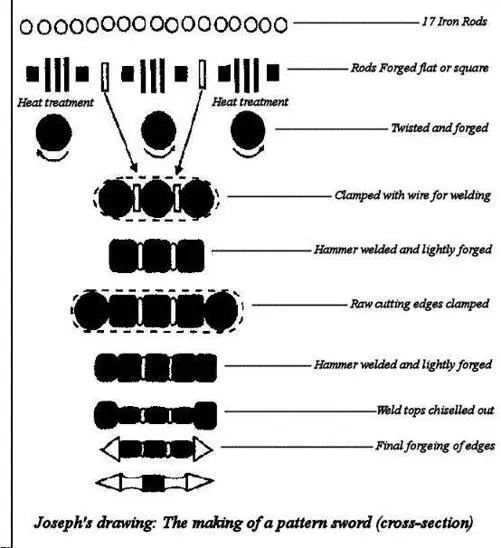

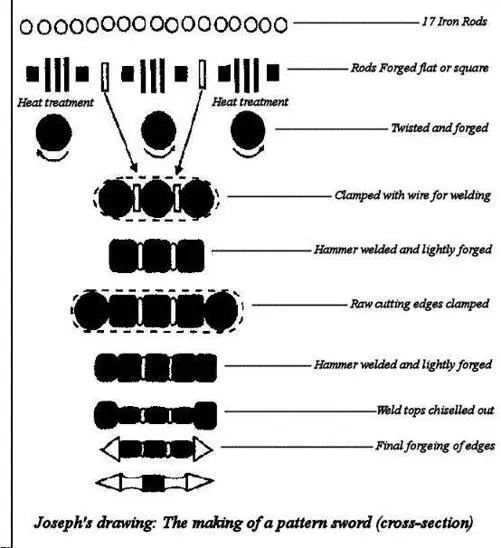

"I'm the last person you should ask. I've seen the statue, but I've never paid much heed to it. It is not the most beautiful sculpture in the world. It is large, though, I remember that." He paused, and then pointed to the set of drawings that I myself had found so strange and incomprehensible. "What are these things, Joseph, these strange symbols?"

Joseph glanced at me and grinned. "Do you know what they mean, Cay?"

When I shook my head, Joseph moved to unwrap the long cloth-wrapped bundle that had clanked so heavily when Ambrose laid it down, and we watched curiously as he extracted a longish, boss-hilted sword, in the style of a Roman cavalry spatha, together with a handful of plain, thin iron rods about the length of his arm, from wrist to shoulder, approximately two handspans. Some of them were round in section, less than the tip of a man's little finger in diameter, others flattened into strips.

Joseph offered the sword, hilt first, to Ambrose. 'That is the finest blade I ever made." He nodded towards the iron rods. "Do you know what those are?"

Ambrose smiled, looking from the sword he now held to the rods.

"Joseph, I have a feeling you will be unsurprised when I tell you I have no idea."

"Well, those are working rods. They're the next sword I will make." He reached into the bundle again and brought out a large, shapeless lump of pasty, whitish material with a chalky consistency and placed it beside the rods. "And this is what I'll use to help me achieve that."

Ambrose prodded the lump with the point of the spatha. "And what is that?"

"Birdshit, for the most part—pigeon dung, in fact— mixed with flour, honey, milk and a little olive oil."

I laughed aloud, for a sudden memory of my Uncle Varrus had sprung into my mind, bringing with it a recollection of many long summer afternoons spent with a small scraper and a metal container, scraping pigeon droppings from the dovecote in the Villa Britannicus, for which I was rewarded in a variety of delightful ways. Ambrose glanced at me askance, thinking we were mocking him, and I held up my hands, palms outward, shaking my head to disclaim any complicity in this.

"It's true," Joseph protested. "One of the oldest secrets of the ancient smiths. A paste made of these ingredients, and coated on the iron during heating and forging, hardens the iron." From the expression on his face, Ambrose was still plainly unconvinced and Joseph went on, laughing now, "I wouldn't lie to you in this, Master Ambrose. If you think of that lump there as being made of a hundred equal parts, then forty of those parts will be pigeon shit, twenty- one of them plain, wheaten flour, fourteen of them honey, twenty-three parts milk, and two parts olive oil. That, you'll see if you count them, makes a hundred, and if you think I came up with that out of my head, you give me too much credit. Now these—" He broke off, his hand outstretched towards the thin iron rods, and turned to me again. "May we look again at Excalibur? It will be easier to explain my point if I have it here, to show you what I mean."

I brought out the great sword and handed it to him, and he held it extended in front of him, gripping the hilt in both of his square, strong, smith's hands, his lips pursed in a low whistle of wonder.

"Even now, I can't believe this tiling exists. Look at the size of it! Unblemished, absolutely flawless. Until I set eyes on this, I would never have believed such a weapon could be made, let alone made so well. God's bones, I

know men who are not as tall as this is long from tip to tip, and so do you! No man, nor no armour in the world, could withstand such a blade." He raised it, straight- armed, until it reared above him to touch the low, vaulted roof above his head, and then he lowered it again swiftly, bringing the cross-hilt close to his face and pointing to the greatest width of the blade as he addressed himself again to Ambrose.

"Look you here, now, at this portion, the thickest and the strongest section. It is, what? three and a half, four fingers wide? Now look here, where the twin blood channels begin, and note the depth to which they sink. Note, too, the patterns in the metal. You see them?"

"Aye, the wavy lines. What causes those?"

'The forging of the sword. Now look here at the parchment and learn a little of the weapon-maker's craft. These marks that mystified you are easily explained." He indicated the strange, stylized markings that had puzzled us.

"If you count, you'll see the entire process of making a sword blade, right there, in ten descending steps. It's an oversimplification, of course, and it gives no indication of the amount of work involved, but to a smith's eye, it's absolutely simple and straightforward. The trick is to realize that you're looking at the thickest part of the blade, the piece I just pointed out to you, just beneath the cross-hilt. Look at the bottom one first. If you were mad enough to saw through the blade at that point, just beneath the cross- guard, and look directly at the sawed-off stump of it, that's what you would see. Then, moving back up to the top one step at a time, you see a reversal of the smithing process, all the way back to the seventeen narrow rods of plain, wrought iron that you started with. Can you see it? Cay, can you?"

I nodded, for what he had described was the missing step between reading Uncle Varrus's observations and notations and seeing them put into effect in very simple terms. Ambrose, however, had never met or known Publius Varrus and had probably never set foot inside a forge. He was staring in perplexity at the drawing. Joseph watched him.

"You have a question, Master Ambrose. Ask away."

"The three large black dots, marked as 'twisted and forged.' What does that mean? I can see the seventeen rods on the first line becoming the flattened and squared pieces on the second, but where did the three come from?"

"Here, here and here," Joseph answered, tapping a finger on the second line. "See, there are three sets of five black rods divided from each other by two whites. Each of those sets of five black rods—three flat in the middle and one square on each flat side—is twisted and forged into a single spiralled rod. We coat each strip of them in the bird dung mixture, bind them together with wire, fire them up, weld one end, just to hold them together, and then clamp that end in a vice. Then, using tongs, we twist the other ends into a spiral. It's tricky, and it takes a long time and many heatings of the metal, because it can only be done when the iron's yellow-hot and soft, and it loses its heat quickly—but in the end, provided you don't do anything stupid, you end up, in each instance, with a single, tightly wound, spiralled rod of layered iron. That's where those markings along the edges of the blade and in the blood channel come from."

Читать дальше