In much the same way, people in North America today tend to feel proprietorial about nouns like “corn” and “bannock,” not realizing that corn has always been the generic Old World term for any kind of grain and that bannock—the simplest form of unleavened bread—is common to every primitive society, no matter what they call it. The Celtic clans of Scotland and Ireland have always called it bannock, and it was their use of the name that the aboriginal peoples of America adopted. The plant Americans call corn, on the other hand, is known as maize in Europe, where it is a coarse, mealy grain fed to cattle. American sweet corn really only came to be known in Europe during and after the Second World War.

Another problematical word for us is the Roman word “mile,” because a modern mile is 1,760 yards, or approximately 1,500 meters. The original Roman mile came from the Latin word mille , meaning a thousand, and a mile was one thousand paces long. Bearing in mind that the average Old World Roman was less than five feet six inches tall, their marching pace would have been short, probably in the range of twenty-six inches to twenty-nine inches, making their mile shorter than a modern kilometer.

And then there are the latifundiae. Few people today have any concept of how highly organized, and even industrialized, the Roman Empire was, sixteen and seventeen hundred years ago. The Romans had a thriving stock market and a highly refined and regulated real estate industry, and the food production and distribution system they constructed to feed their citizenry, founded upon a system of enormous ranches and collective farming establishments called latifundiae, was extremely sophisticated even by today’s standards. These were private enterprises, run by corporations and funded and owned by investors, and they produced grain, cattle, wines, fruits and vegetables, and other commodities in huge quantities for shipment to markets throughout the Empire.

The Latin word magister gives us our modern words “magistrate” and “magisterial,” but it was a word in common use in the Roman Army in the fifth century. In terms of its use, it appears to have had two levels of meaning, and I have used it in both senses throughout this book: The first of these was the literal use, where a student or pupil would refer to his teacher or mentor as magister (master) with all appropriate deference. The second usage, however, resembled the way we today use the term “boss,” denoting a superior—officer or otherwise—whose title entails the accordance of a degree of respect but falls far short of the subservience suggested by the use of the word “master.”

Similarly, the word ecclesia gives us our modern word “ecclesiastical,” but the original meaning of the word was a church, particularly a permanent church, built of stone.

Citrus wood is well documented as being the most precious wood in the Ancient World, but we have no idea what it was like. No trace of it survives. It is one of the earliest known instances of a precious commodity being exploited to extinction.

And finally, a word about horse-troopers. Roman cavalry units were traditionally organized into turmae (squadrons) and alae (battalions). There were thirty to forty men in a turma (the singular form of turmae) and the strength of the alae ranged anywhere from sixteen to twenty-four turmae, which meant that a cavalry battalion could number between four hundred eighty and nine hundred sixty men. The contus, a substantial, two-handed cavalry spear, was the weapon of many heavy cavalry turmae and those troops were known, in turn, as contus cavalry.

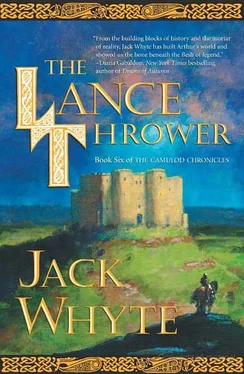

FORGE BOOKS BY JACK WHYTE

THE CAMULOD CHRONICLES

The Skystone

The Singing Sword

The Eagles’ Brood

The Saxon Shore

The Fort at River’s Bend

The Sorcerer: The Metamorphosis

Uther

The Lance Thrower

Praise for Jack Whyte and the Camulod series

“Of the scores of novels based on Arthurian legend, Whyte’s ‘Camulod’ series is distinctive, particularly in the rendering of its leading players and the residual Roman influences that survived in Britain during the Dark Ages.”

—The Washington Post

“Whyte has done an excellent job of constructing a viable pre-Arthurian world. His fifth-century Europe is evocative, earthy, and well researched.”

—Romantic Times

“As Whyte waves off the fog of fantasy and legend surrounding the Arthurian story, he renders characters and events real and plausible.”

—Booklist

“Whyte shows why Camulod was such a wonder, demonstrating time and again how persistence, knowledge and empathy can help push back the darkness of ignorance to build a shining future.”

—Publishers Weekly

“Whyte’s story has an undeniable power that goes beyond the borrowed resonances of the mythic tales he’s reworking.” a

—Fantasy & Science Fiction

“A rousing historical adventure, full of hand-to-hand combat, hidden treasures, and last-minute escapes, a refreshing change from the many quasi-historical, politically correct Arthurians out there.”

— Locus on The Skystone

“It’s one of the most interesting historical novels that I’ve ever read and I’ve read plenty.”

—Marion Zimmer Bradley on The Skystone

This is a work of fiction. All the characters and events portrayed in this book are either products of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously.

THE LANCE THROWER

Copyright © 2004 by Jack Whyte

All rights reserved, including the right to reproduce this book, or portions thereof, in any form.

A Forge Book

Published by Tom Doherty Associates, LLC

175 Fifth Avenue

New York, NY 10010

www.tor-forge.com

Forge ®is a registered trademark of Tom Doherty Associates, LLC.

eISBN 9781466822191

First eBook Edition : May 2012

First edition: October 2004

First mass market edition: November 2005

The author and publisher have provided this e-book to you without Digital Rights Management software (DRM) applied so that you can enjoy reading it on your personal devices. This e-book is for your personal use only. You may not print or post this e-book, or make this e-book publicly available in any way. You may not copy, reproduce or upload this e-book, other than to read it on one of your personal devices.

Copyright infringement is against the law. If you believe the copy of this e-book you are reading infringes on the author’s copyright, please notify the publisher at: us.macmillanusa.com/piracy.