It was the speed at which his questions came that finally opened Penny’s eyes. They were immersed in a rapid-fire discussion of the Essington brothers, Millie’s and Julia’s husbands, when the scales fell. She stopped midsentence, stared at him for a moment, then shut her lips. Firmly.

He accorded her glare no more than an arched brow, a what-did-you-expect look.

Indeed. Tossing her napkin on the table, she rose. He, more languidly, rose, too.

“If you’ll excuse me, I believe I’ll retire for the night.”

She turned, but by then he’d reached her. He walked beside her to the door. Closing his hand about the knob, he paused and looked down at her. Waited…until she steeled herself, looked up, and met his eyes.

“No game, Penny. I need to know. Soon.”

They were no more than a foot apart; regardless of her senses’ giddy preoccupation, the look in his midnight eyes was unmistakable. He was deadly serious. But he was dealing with her straightly, no histrionics, no attempt to dazzle her, to pressure her as only he could.

He had to know he could; that moment in the orchard had demonstrated beyond question how much sensual power he still wielded over her.

If he wished to use it.

Tilting her head, she swiftly studied his eyes, realized, understood that he’d made a deliberate choice not to invoke their personal past, not to use the physical connection that still sparked between them against her, to overcome, overwhelm, and override her will.

He was dealing with her honestly. Just him and her as long ago they’d used to be.

Moved, feeling oddly torn—tempted to grasp the chance of dealing openly with him again—she raised a hand, briefly clasped his arm. “I will tell you. You know that.” She drew in a tight breath. “But not yet. I do need to think—just a bit more.”

He searched her eyes, her face, then inclined his head. “But only a little bit more.” He opened the door, followed her through. “I’ll see you in the morning.”

She nodded a good night, then climbed the stairs.

Charles watched her go, then headed for the library.

In one respect his prediction went awry; he saw her next very late that night.

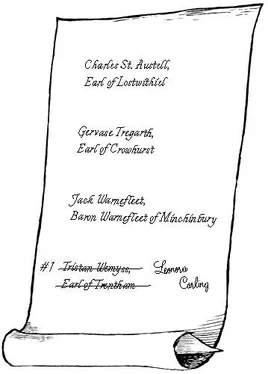

After spending three hours leafing through Burke’s Peerage and Debrett’s , studying Amberly’s connections, then looking for locals with connections to the Foreign Office or other government offices, trying to identify who Penny might feel she should protect, all to no avail, he turned down the lamps and climbed the stairs as the clocks throughout the house struck half past eleven.

Halting on the landing, he looked up at the huge arched window, at the stained glass depicting the St. Austell family crest. Rain beat a staccato rhythm against the panes; the wind moaned softly. The elements called, tugged at that wilder, more innocent side of him the years had buried, teased, tempted…

Lips curving in cynical self-deprecation, he took the left branch of the stairs and climbed upward, heading not for his apartments as he’d originally intended but to the widow’s walk.

High on the Abbey’s south side immediately below the roof, the widow’s walk ran for thirty feet, a stone-faced, stone-paved gallery open on one side, the wide view of the Fowey estuary framed by ornate railings. Even in deepest night with the moon obscured by cloud and the outlook veiled by rain, the view would be magnificent, eerily compelling. A reminder of how insignificant in Nature’s scheme of things humans really were.

His feet knew the way. Courtesy of the years, he moved silently.

He halted just short of the open archway giving onto the walk; Penny was already there.

Seated on a stone bench along the far wall, one elbow on the railing, chin propped on that hand, she was staring out at the rain.

There was very little light. He could just make out the pale oval of her face, the faint gleam of her fair hair, the long elegant lines of her pale blue gown, the darker ripple of her shawl’s knotted fringe. The rain didn’t quite reach her.

She hadn’t heard him.

He hesitated, remembering other days and nights they’d been up here, not always but often alone, just the two of them drawn to the view. He remembered she’d asked for time alone to think.

She turned her head and looked straight at him.

He didn’t move, but Penny knew he was there. To her eyes he was no more than a denser shadow in the darkness; if he hadn’t been looking at her, she’d never have realized.

When he didn’t move, when she sensed his hesitation, she looked back at the wet night. “I haven’t yet made up my mind, so don’t ask.”

She sensed rather than heard his sigh.

“I didn’t realize you were here.”

He’d thought her in her chamber; he couldn’t have known otherwise. She returned no comment, unperturbed by his presence; he was too far away for her senses to be affected—she didn’t, otherwise, find him bothersome to be near. And she knew why he’d come there—for much the same reason she had.

But now he was present, and she was, to o…she tried to predict his next tack, but he surprised her.

“You weren’t that amazed to learn I’d been a spy. Why?”

She couldn’t help but smile. “I remember when you returned for your father’s funeral. Your mother was…not just happy to see you, but grateful. I suppose I started to wonder then. And she was forever slipping into French when she spoke to you, far more than she usually does, and you were so secretive about which regiment you were in, where you were quartered, which towns you’d been through, which battles…normally, you would have been full of tales. Instead, you avoided talking about yourself. Others put it down to grief.” She paused, then added, “I didn’t. If you’d wanted to hide grief, you would have talked and laughed all the harder.”

Silence stretched, then he prompted, “So on the basis of that one episode…”

She laughed. “No, but it did mean I had my eyes open the next time you appeared.”

“Frederick’s funeral.”

“Yes.” She let her memories of that time color her tone; Frederick’s death had been a shock to the entire county. “You were late—you arrived just as the vicar was about to start the service. The church door had been left open, there were so many people there, but the center aisle had been left clear so people could see down the nave.

“The first I or anyone knew of your presence was your shadow. The sun threw it all the way into the church, almost to the coffin. We all turned and there you were, outlined with the sun behind you, a tall, dramatic figure in a long, dark coat.”

He humphed. “Very romantic.”

“No, strangely enough you didn’t appear romantic at all.” She glanced at him. He was concealed within the shadows of the archway, leaning back against the arch’s side, looking out; she could discern his profile, but not his expression. She looked back at the rain-washed fields. “You were…intense. Almost frighteningly so. You had eyes for no one but your family. You walked to them, straight down the nave, your boots ringing on the stone.”

She paused, remembering. “It wasn’t you but them, their reactions that made me…almost certain of my suspicions. Your mother and James hadn’t expected to see you; they were so grateful you were there. They knew. Your sisters had been expecting you, and were simply reassured when you arrived. They didn’t know.

“Later, you explained you’d been held up, and that you had to rejoin your regiment immediately. You didn’t exactly say, but everyone assumed you meant in London or the southeast; you intended to leave that night. But it had rained on and off for days—it rained heavily that night. The roads were impassable, yet in the morning you were gone.”

Читать дальше