By the time they arrived, the citadel had already fallen, the last two hundred and fifty Cathars forcibly marched through the barbican gates. They were put to the torch by order of the Pope’s envoy, a white-robed Dominican priest, thus bringing to a fiery close the thirty-year-long Albigensian Crusade.

As had happened on all of his previous visits to Montségur, Cædmon found himself contemplating the tragedy with renewed vigour. Everywhere he looked the ghost of those humble heretics hovered amidst the ruined ramparts and shattered curtain walls, all that remained of the Cathars’ mountaintop eyrie. A limestone monument to the dead, it invoked the memory of that other doomed mountaintop fortress, the Jewish bastion at Masada. Which no doubt explained the heart-rending aura that clung to the citadel like a finely spun burial shroud.

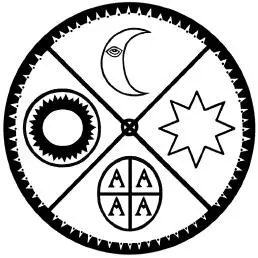

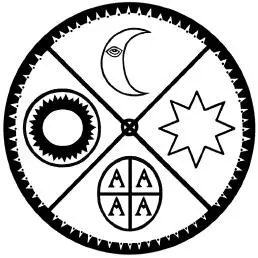

Opening the flap on his field jacket, Cædmon removed his BlackBerry. Because of the precipitous hike up the winding mountain trail from the village below, he’d dressed in khaki cargo pants, a practical long-sleeved shirt and rugged boots. Accessing the photo log on the BlackBerry, he stared at the symbols incised on the medallion: star, sun, moon and four strangely-shaped ‘A’s arranged in a cruciform.

His gaze zeroed in on the four ‘A’s.

Yesterday, on the train ride from Paris, he’d carefully examined a map of the Languedoc. With numerous place names in the region beginning with the letter ‘A’, it would take a lifetime to search each and every one. Moreover, the Languedoc encompassed an area that measured nearly sixteen thousand square miles. Most of it, mountainous terrain. The disheartening reality was that the Grail could have been hidden anywhere within those sixteen thousand square miles.

He skipped to the next photograph, a close-up of the engraved text on the medallion’s flipside. The first two lines, written in the Occitan language, read: ‘In the glare of the twelfth hour, the moon shines true.’ A curious turn of phrase since the moon was most often associated with the night sky. The last line of text had been scribed in Latin. Reddis lapis exillis cellis . ‘The Stone of Exile has been returned to the niche.’ While the meaning was obvious, it was also frustratingly vague, no mention made of where ‘the niche’ was located.

The mystery compounding, Cædmon took a deep breath, filling his lungs with the pine-scented air as he stared at the craggy mountains in the near distance. Terra incognita.

Worried that he’d journeyed to Montségur in vain, he gazed at the barren courtyard beneath the ramparts. Two blokes who’d hauled surveying equipment to the citadel were toying with a transit-level. Another pair, who were filming a documentary, had just set a very professional-looking video camera on to a tripod. A tour group on the far-side of the courtyard was taking turns reading aloud from Wolfram von Eschenbach’s Parzival.

Cædmon suspected that, like him, they were all attempting to solve the mystery of the Cathars’ mountaintop –

Mountain!

‘Bloody hell,’ he whispered, hit with a sudden burst of inspiration.

Sliding his rucksack off his shoulder, he hurriedly loosened the drawstrings, retrieving a small leather-bound journal and a sharpened pencil. His hand visibly shaking, he opened the journal to the first blank page and drew one of the ‘A’s from the medallion cruciform.

His breath caught in his throat.

It’s not an ‘A’ … it’s a mountain peak!

Taken aback by the revelation, Cædmon hitched his hip on to the battlement as he examined the digital photos on the BlackBerry with fresh eyes. If he was right, it meant that, rather than four ‘A’s, there were four mountain peaks depicted on the medallion. A pictogram of the landscape visible from Montségur. Hope renewed, he stared intently at the other engraved symbols.

Certain that the star and the sun represented the heliacal rising of Sirius, that left the moon in the top quadrant to decipher. An age-old symbol found in almost every culture, its meaning and significance was myriad. Birth. Death. Resurrection. Cyclical time. Spiritual light in the dead of night.

But how did any of that relate to the four mountain peaks?

‘ “In the glare of the twelfth hour, the moon shines true,” ’ he quietly recited, the moon not only depicted on the medallion, but specifically mentioned on the reverse inscription.

Could the ‘moon’ be the key to unlocking the riddle of the Montségur Medallion?

Again, he was struck by the strange reference to time. Noon, the twelfth hour of the day, was the apogee of light, when the sun, not the moon, shone at its brightest. Traditionally, ‘noon’ also correlated to the cardinal direction of ‘south’. To this day, the French word ‘midi’ meant ‘noon’ and ‘southern’. As in the Midi-Pyrénées, or southern Pyrenees, where Montségur was located.

What if the ‘moon’ referred to a specific mountain located south of Montségur?

Anxious to test the hypothesis, Cædmon quickly checked the online map feature on his BlackBerry.

‘Damn,’ he muttered a few moments later, not getting a single hit.

On a twenty-first-century map.

Undaunted, he next pulled up an Oxford University search engine for the map collection at the Bodleian Library. Just as he’d hoped, the Bod had a thirteenth-century map of the Languedoc archived online. Heart beating at a brisk tattoo, he clicked on it.

‘Christ.’

Shaking his head in disbelief, Cædmon double-checked the crudely rendered chart. He then lurched to his feet and turned about face, towards the granite peak that loomed on the southern horizon. Mont de la Lune.

‘Moon Mountain’ as it had been called eight hundred years ago.

He barely suppressed the urge to rear his head and shout a joyful hosanna. While the clue might not lead to the Grail, it was a signpost. A new direction in which to venture forth.

On a wing, and even a prayer, so goeth the intrepid Fool .

Anxious to be on his way, Cædmon hurriedly shoved the BlackBerry into his jacket pocket and returned the journal to his rucksack. He then rushed towards the stone steps that led from the ramparts to the courtyard below, an unshaven, khaki-clad wayfarer ready to embark on la quête du Graal.

God help him .

48

Grande Arche Belvedere, Paris

1059 hours

‘Hey, Katie. What’s the matter?’ Finn slid his Oakley sunglasses on to the top of his head. ‘And please don’t tell me that you’re scared of heights.’ Standing on the rooftop of the Grande Arche building, at the eastern side of the belvedere, they had a bird’s-eye-view of the Axe Historique, a.k.a. the Champs-Élysées, thirty-five storeys below. With all of the ultra-modern architecture in the near vicinity, the area resembled a cityscape from a sci-fi movie.

Although Finn didn’t consider it much of a tourist attraction, a crowd nonetheless shuffled along the barricaded perimeter of the rooftop. Bright-blue telescopes were set up every ten feet or so, tourists plopping coins into the slots so they could ooh and ahh over the wonders of Paris magnified umpteen times.

Kate seated herself on a nearby bench. ‘I’m concerned about this so-called “mission op”,’ she told him in a subdued tone of voice. ‘After everything that happened yesterday, is it prudent to go on the offensive?’

Читать дальше