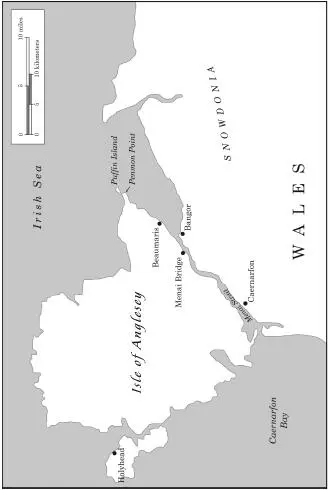

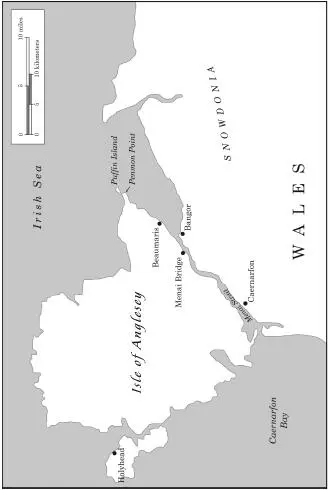

So this was the Isle of Anglesey. Runcorn stood on the rugged headland and stared across the narrow water of the Menai Strait towards the mountains of Snowdonia and mainland Wales, and he wondered why on earth he had chosen to come here, alone in December. The air was hard, ice-edged, and laden with the salt of the sea. Runcorn was a Londoner, used to the rattle of hansom cabs on the cobbles, the gas lamps gleaming in the afternoon dusk. Every day he was surrounded by the sing-song voices of costermongers, the cries of news vendors, drivers of every kind of vehicle—broughams to drays—and the air carried the smell of smoke and manure.

This isolated island must be the loneliest place in Britain, all bare hills and hard, bright water, and silence except for the moan of the wind in the grass. The black skeleton of the Menai Bridge had a certain grace, but it was a cold elegance, not the low, familiar arches across the Thames. The few lights flickering on in the town of Beaumaris behind him indicated nothing like the vast city he was used to, teeming with the passions, the sorrow, and the dreams of millions.

Of course the reason he was here was simple. Runcorn had nowhere else in particular to be for Christmas, no family. He lived alone. He knew many people, but they were colleagues rather than friends. He had earned his promotions until he was now, at fifty, a senior superintendent in the Metropolitan Police, separated by office from those he had once worked beside. But he was not a gentleman, like those of his own rank. He had not the polish, the confidence, the ease of speech and grace of movement that comes with not having to care what people thought of you.

He smiled to himself as the wind stung his face. Monk, his colleague many years ago, one of his few friends, had not been born a gentleman either, but somehow he had always managed to seem like one. That used to hurt, but it did not anymore. He knew that Monk was human too, and vulnerable. He could make mistakes. And perhaps Runcorn himself was wiser.

The last case in which they had worked together had been difficult and in the end ugly. Now Runcorn was tired of the city and he was due several weeks of leave. Why not take it somewhere as different as possible? He would refresh his mind away from the familiar and predictable, take long walks in the open, think deeply for a change.

The sun was sinking in the southwest, shedding brilliant, burning light over the water. The land was dark as the color faded and the headlands jutted purple and black out of the sea. Only the uplands, ribbed pale like crumpled velvet, still caught the last rays of light.

How long was winter twilight here? Would he soon find himself lost, unable to see the way back to his lodgings? It was bitterly cold already. His feet were numb from standing. Turning, he started to walk towards the east and the darkening sky. What was there to think about? He was good at his job, patient, possibly a little pedestrian. He never had flashes of brilliant intuition, but he got where he needed to. He had succeeded far more than any of the other young men who had started when he had. In fact, his own success had surprised him.

But was he happy?

That was a stupid question, as if happiness were something you could own and have for always. He was happy at times, as for example when a case was closed and he knew he had done it well, found a difficult truth and left no doubts to haunt him afterwards, no savage and half-answered questions.

He was happy when he sat down by the fire at the end of a long day, took the weight off his feet, and ate something really good, like a thick-crusted ham-and-egg pie, or hot sausages with mashed potatoes. He liked good music, even classical music sometimes, although he would not admit it, in case people thought he was putting on airs. And he liked dogs. A good dog always made him smile. Was that enough?

He could only just see the road at his feet now. He thought about the huge bridge behind him, spanning the whole surge and power of the sea. What about the man who built that? Had he been happy? He had certainly created something to marvel at, and changed the lives of people far into the future.

Runcorn had untangled a few problems, but had he ever built anything, or did he always use other people’s bridges? Where did he go, anyway? No more than home to bed. Tonight it was to be an unfamiliar lodging house. It was comfortable. He would sleep well, he usually did. Certainly it was warm enough, and Mrs. Owen was an agreeable woman, generous in nature.

The next morning was sharp and cold, but a pale sun struggled over the horizon, milky soft through a fine veil of cloud, which Mrs. Owen assured him would burn off soon. The frost was only a dusting of white here and there, enough to make the hollows stand out on the long, uneven lawn stretching down to the big yew tree.

Runcorn ate a hearty breakfast, talked with Mrs. Owen for a little while because it was only civil to appear interested as she told him about some of the local places and customs. Afterwards he set out to walk again.

This time he headed uphill, climbing steadily until nearly midday when he turned and gazed out at a cloudless sky, and a sea shimmering unbroken into the distance.

He stood there for some time, lost in the enormity of it, then gradually descended. He was on the outskirts of Beaumaris again when he turned a corner in the road and came face-to-face with a tall, slender man of unusual elegance, even in his heavy, winter coat and hat. He was in his mid-thirties, handsome, clean-shaven. They both stopped, staring at each other. The man blinked, uncertain except recognizing Runcorn’s face as familiar.

Runcorn knew him instantly, as if it had been only a week ago they had met. But it was longer than that, much longer. It had been a case of suicide suspected to be a murder. John Barclay had lived in a house backing onto the mews where the body had been found. It was not Barclay whom Runcorn remembered; it was his widowed sister, Melisande Ewart. Even standing here in the middle of this bright, windy road, Runcorn could see her face as clearly as if it were she who were here now, not her arrogant, unhelpful brother.

“Excuse me,” Barclay said tensely, stepping around Runcorn as if they had been strangers and walking on up the road, lengthening his stride. But Runcorn had seen the recognition in his face, and the distaste.

Was Melisande here too? If she was, he might see her, or at least catch a glimpse. Did she still look the same? Was the curve of her hair as soft? The way she smiled and the sadness in her had continued to haunt him in the year since they’d last met.

It was ridiculous for him to think of her still. If she remembered him at all, it would be as a policeman determined to do his job regardless of fear or favor, but with possibly a modicum of kindness. It was her courage, her defiance of her brother Barclay in identifying the corpse and taking the witness stand, that had closed the case. He had always wondered how much that had cost her afterwards in Barclay’s displeasure. There had been nothing he could do to help.

He began walking again, around the bend in the road and past the first house of the village. Was she staying here also? He quickened his step without realizing it. The sun was bright, the frost nothing more than sparkling drops in the grass.

How could he find out if she was here, without being overeager? He could hardly ask, as if they were social acquaintances. He was a policeman who had investigated a death. It would be pointless to see her, and much too painful. Chastising himself, he thought what a fool he was to have even thought about it.

Читать дальше