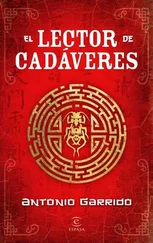

“Really?” Feng was surprised. “I would have thought he’d been making the most of your considerable talent as a wu-tso. ”

Cí choked, quickly blaming the rice wine. He tried to be as offhand as he could and said something about having studied the northern barbarians a little at the Ming Academy. Luckily, Blue Iris didn’t pursue the matter.

For the rest of the meal, Feng filled Cí in on his successes since they’d parted, his move to the Water Lily Pavilion, and how he owed it all to Blue Iris.

“My life changed the moment I met her,” he said, stroking his wife’s hand, though she responded by retracting her hand and excusing herself, saying she’d bring the tea.

They both watched her make her way to the kitchen—without the aid of the walking stick she always carried. Cí began thinking about her skin; he couldn’t help it. Feng broke the silence.

“You’d never guess she was blind,” he said lightly. “She could run the length of this place and wouldn’t bump into a thing, I bet you.”

Cí nodded. He felt like a traitor on so many fronts. If he didn’t tell Feng the truth, or at least part of it, he was going to burst.

First he made Feng promise not to tell anyone.

“Not even Blue Iris,” Cí said.

Feng swore on his ancestors’ souls.

Cí told him about the circumstances of his departure from the village. He told him he was a fugitive. He told him about Gray Fox’s imminent return. Then he went on to detail the case he was really working on, and the progress he’d made, and Kan’s conviction that it had something to do with a plot against the emperor.

“Interesting,” said Feng. “I’m thinking how I might be of help…This other youth, Gray Fox was it? Hmm. I wouldn’t worry about him. When he gets back, he and I are going to have a little talk.”

Cí looked in Feng’s eyes. All that trust—and Cí was on the verge of betraying it. He felt a pang in his stomach. He was just about to reveal the part of the story about Kan’s suspicions of Blue Iris when they heard her coming back with the tea.

Again, Cí was captivated by her movements, even performing such a simple task as pouring drinks. There was a deep calm in her, and it acted on him like a balm.

When they’d drunk their tea, Feng issued some whispered instruction to a servant. “Here,” he said when the servant returned, handing over a sheaf of papers to Cí. “These, I believe, are yours.”

“But—but,” stammered Cí.

Feng nodded.

It was the Certificate of Aptitude he needed to take the Imperial exams, and there was no mention of his father’s dishonor, nothing about any obstacles. It was clean. He would be allowed to take the exams. Tears sprang to his eyes as he looked again to his old master.

Just then, the servant came in, saying a group of businessmen were there to see Feng. When Feng came back, he reported that one of his goods convoys had been attacked near the border.

“The attackers were repelled,” he said, “but we’ve lost men, and some of the goods, too. I have to go immediately.”

Cí felt even worse. He’d have given anything to admit the part of the story about Blue Iris, but he wasn’t going to have a chance now. As they embraced, Feng whispered in his ear.

“Be careful with Kan,” he said. “And look after Blue Iris for me.”

And with that, he was gone.

31

Feng had said he’d be away for only a few days, but Cí couldn’t imagine being alone with Blue Iris for any amount of time. He spent the afternoon trying to reassemble the bronze maker’s green mold but couldn’t stop thinking about her. And when the bell rang for dinner, he realized he’d made no progress whatsoever.

It would have been too much of a discourtesy not to attend dinner, so Cí quickly washed, shaved, and went down. Blue Iris was waiting for him. He sat across from her, not daring to look straight at her. He glanced up and couldn’t help but admire the sight: her sheer blouse gave him a clear view of large expanses of her skin. When she handed him a plate of soybean shoots, it was her breasts in particular, or their outlines, that magnetized his gaze. He knew she couldn’t see him drinking her in, so he looked, more intensely than ever before.

“What are you looking at?” she said.

“Nothing!”

“Nothing? Don’t you like the food? There are even figs somewhere here…”

“Oh, yes!” he said, taking one of the strange, dark little fruits. “Of course.”

“So would you like to hear about the work I used to do?”

“Very much,” he said. Reaching for more fruit, his hand brushed hers, which sent shivers through his entire body.

“If you really want to hear about the life of a nüshi , you might want to drink a little more. It is a tale full of bitterness.” She sighed, and there was anguish in her voice. “When I entered the emperor’s service I was a child, but not for much longer; one doesn’t stay innocent doing such work. He must have seen something in me, and he wasted no time seizing it. I grew up among concubines. They were my sisters, and they taught me how to live in those conditions, living only to please the Heaven’s Son. They gave me all the necessary refinements, the subtleties, the arts. Instead of learning to play, I learned to kiss and lick…Instead of laughing, I learned how to please.

“Confucian texts? The classics? Not for me. The books that were read to me as a child were all about the art of pleasure: the Xuannüjing , or Manual of a Dark Woman ; the Xufangneimishu , or Preface to the Secret Bedroom Arts ; the Ufangmijue , or Bride’s Secret Formula ; the Unufang , or Recipes of a Simple Lady. As my body changed and I became a woman, a deep hate was also taking hold of me, as intense as my experience of blindness. And the more I hated him, the more he wanted me.

“I learned to be better than all the rest in pleasuring him. I honed my skills in the bedroom knowing that the greater his desire, the greater my revenge would also be.

“That was my desire.” She seemed to turn her pupils on Cí. “I soon became his favorite. He longed for me night and day. He coveted me, licked me, penetrated me. And when he’d taken all of my body, when there was nothing physical left for me to give, his desire shifted to possessing my soul.”

Cí contemplated her crestfallen face. He felt grief grip his stomach. The tears were flowing freely down her smooth cheeks.

“You don’t have to go on,” he said. “I—”

“You mean you don’t want to hear more? You don’t want to hear what it’s like to feel used, empty, your self-respect in tatters?

“I became a husk of a person. My youth was a wounded time, and I hated it completely. The funny thing was the other concubines’ envy. Any one of them would have changed places with me, even with my blindness. But, unlike all of them, I couldn’t have children.” She laughed bitterly. “I got what I’d set out to achieve, and the price was my dignity. When it reached the point where he called out my name in the night, when he needed me like life itself, that was when I began denying him. But the happiness I felt at that control quickly became sadness; my only desire had been achieved, and there was nothing left. He cried, he screamed, he beat me. He claimed to have fallen ill, but of course there was no cure any doctor could provide. His proud penis became nothing more than a soft silk sheet, and no concubine, no courtesan, not one prostitute in the whole kingdom was able to give him what I’d been giving him.”

Читать дальше