“They might not have been able to,” chided the professor. “Anyone else want to say anything?”

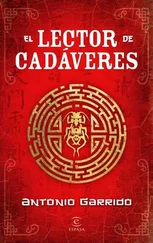

Cí saw that the professor noticed one of the students—Cí had overheard him called Gray Fox, a fitting name given his gray-streaked hair—kept yawning, but the instructor said nothing. He covered the baby’s corpse and asked Xu to bring the next. Xu took the opportunity to bring Cí in and introduce him as the resident necromancer. The students looked at his outfit with disdain.

“We’re not interested in tricksters,” said the professor. “None of us here believe in necromancy.”

Cí withdrew, disconcerted. Xu whispered to him to take off the mask and stay alert. The next corpse was an ashen old man who had been found dead behind a market stall.

“Death by starvation,” said one of the students, looking closely at the corpse with its protruding bones. “Swollen ankles and feet. Approximately seventy years old. Natural causes, therefore.”

Again, the professor agreed with the evaluation, and everyone congratulated the student. Cí saw how Gray Fox went along with it but was clearly being insincere in his praise. Xu and Cí brought the third corpse in a large pine coffin. When they removed the lid, the students at the front recoiled, but Gray Fox came forward, immediately quite interested.

“Looks like a chance for you to show your talents,” said the professor.

The student replied with an ironic smile and approached slowly, his eyes glittering as though the coffin contained a treasure. Cí watched as the student took out a sheet of paper, an inkstone, and a brush. His approach was very similar to the one Cí had seen Feng take in examinations.

First Gray Fox inspected the corpse’s clothes: the undersides of the sleeves, inside the shirt, trousers, and shoes. Then, having removed the clothes and scrutinized the body, he asked for water, which he used to clean the blood-spattered skin thoroughly. Next he measured the body and announced that the deceased was at least two heads taller than an average man.

He began examining the swollen face, which had a strange puncture on the forehead that exposed a bit of the skull. Instead of cleaning it, the student extracted some mud, saying the puncture was most likely the result of a fall, the head having struck the edge of paving stones or cobblestones. He made a note and then described the eyes, which, half open and dull, were like those of a dried fish; the prominent cheekbones; and the wispy mustache and strong jaw. Then he mentioned the long gash that ran from one side of the throat, across the nose, and all the way to the right ear. He looked closely at the edges of the cut and measured the depth. Smiling, he wrote something else down.

He moved on to the muscular torso, noting eleven stab wounds; then he scanned the groin; the small, wrinkled penis; and the thighs and calves, which were also muscular and hairless. Cí helped him turn the corpse over; aside from the bloodstains, the back was unmarked. The student stood back, looking ever more pleased.

“So?” said the professor.

The student took his time before answering, looking at each person individually. He clearly enjoyed performing. Cí raised an eyebrow but paid attention.

“This is obviously an unusual case,” began the student. “The man was young, very strong, and ended up stabbed and with his throat slit. A shockingly cruel murder, which seems to point to there having been a very vicious fight.”

The professor gestured for the student to continue.

“At first glance we might think that there were several assailants—there would have been several of them to overcome a hulk like this—and the many stab wounds attest to that. The number of injuries indicates the fight lasted some time, before someone delivered the decisive wound to the throat. After that, the victim fell forward, causing the strange rectangular mark on the forehead.” Here the student paused for effect. “And the motive? Perhaps we ought to think of several: from a simple tavern brawl to an unpaid debt or old feud or even a dispute over some beautiful ‘flower.’ But the most likely motive is robbery, given the fact the body’s been stripped of all valuables, including the bracelet that should have been…here,” he said, pointing to a tan mark at the wrist. “A magistrate would have done well to order the immediate vicinity searched, paying particular attention to taverns and any troublemakers either showing wounds or throwing money around.” The student closed his notebook, covered the corpse, and stared at the group, waiting for his applause.

Cí remembered what Xu had said about the possibility of tips if they groveled, and went over to congratulate the student, but the student looked at him with disdain.

“Stupid show-off,” muttered Cí, turning away.

“How dare you!” Gray Fox grabbed his arm.

Cí shrugged him off and squared up to the student, ready to argue, but before he could reply, the professor was between them.

“So, it seems the sorcerer thinks we’re loudmouths,” said the professor. Looking at Cí more closely, his face changed. “Do I know you?”

“I don’t think so, sir. I haven’t been in the capital long,” he lied. As he said it, though, he realized the professor was Ming, the man to whom he’d tried to sell his copy of the penal code at the book market.

“Are you sure? Well, anyway…I think you owe my student an apology.”

“Or maybe he owes me one.”

At Cí’s impertinence, a murmur went around.

Xu stepped in. “Please, sir, forgive him. He’s been quite out of sorts lately.”

But Cí wasn’t backing down. He wanted to wipe the smile off the conceited student’s face.

He turned to Xu and whispered, “Put a bet on me. Everything you’ve got. It’s what you know best, right?”

18

Professor Ming resisted betting at first, but once he admitted a bit of curiosity, his students urged him on, and he agreed to the challenge. Xu skillfully upped the bets, making a show of worrying that he’d lose everything.

“If you mess this up,” warned Xu, “I swear I’ll sell your sister for less than the price of a pig.”

Cí wasn’t daunted. He asked the group to give him some space and took out instruments for his examination: a small hammer, forceps made from bamboo, a scalpel, a small sickle-like object, and a wooden spatula. Beside these he placed a washbasin, gourds containing water and vinegar, paper, and a brush.

Cí had some doubts about Gray Fox’s inspection, and Cí was ready to see if he was right.

He went first to the corpse’s nape, working his fingers from there up along the scalp to the crown of the head, and then inspecting the ears with the help of the little spatula. Then he went downward from the neck, examining the muscular shoulders, upper arms, elbows, and forearms, stopping at the right hand and paying particular attention to something at the base of the thumb.

A circular callus .

He made a note.

He checked the spine, the buttocks, and the legs for injuries before cleaning the face, neck, and torso—properly, with water and vinegar. He spent a good deal of time on the stab wounds, measuring and probing, and then concluding that at least three were fatal.

Just as I suspected.

Then the terrible throat wound: shaking his head, he measured it and made a note of the tears at the edges. Last came the face. Using the forceps inside the nose and mouth, he extracted a whitish substance. He made another note.

“We’re waiting,” warned the professor.

But Cí refused to be hurried. A hundred facts were swirling in his mind, and he still hadn’t quite come to the answer. He returned to the face, where, now that it was clean, he noticed some small scratches on the cheeks. He moved to the mark on the forehead, which he concluded couldn’t have been caused by an impact at all; the edges of the rectangular mark were too neat to be anything but an incision. The mud stuck in the flesh was a red herring, he decided.

Читать дальше