“What are you driving at?” he asked.

“I don’t want Ruiz to figure out I might have fooled him. He has a great deal of contempt for me, and I want to keep it alive.”

“Why?”

“I think our only chance is for one of us to surprise him while Morrison’s over here on the sand bar, and you’re never going to get behind him if you live to be a hundred. I watched him all day, and that boy’s cool.”

“Also too tough to be knocked off his feet by a woman,” Ingram said. “If he looks easy, it’s just because you’re seeing him alongside Morrison.”

“It wouldn’t have to be for more than three or four seconds, if we timed it right. However, we’ll table that for the moment, and get back to Patrick Ives. It doesn’t add up. He was aboard. They say he drowned.”

“Are you sure he was aboard?” Ingram asked quietly.

“Positive. I managed to get Morrison talking about him a little tonight. Hollister was Patrick Ives, and nobody else. He never actually told Morrison that was his name, but he practically admitted it wasn’t Hollister. And of course Morrison knew that Hollister-Dykes Laboratories thing was a lot of moonshine. He told Morrison he was an M.D. who’d got a bum deal from the ethics committee of some county medical association over a questionable abortion. That’s pure Ives.”

“Just a minute,” Ingram said. “Was he a drug addict?”

“You mean narcotics?” she asked, puzzled.

“Heroin.”

“No. He was a lot of other things, but not that.”

“Are you sure?”

“Yes, of course. Unless he’s acquired the habit in the past four months, at the age of thirty-six, which would seem a little doubtful.”

“All right, one more question. Are you absolutely sure he was an aerial navigator during the war?”

“Yes.”

“You’re not just taking his word for it? I gather he was quite a liar.”

“He was, but this is from personal knowledge. I knew him during the war, when he was taking flight training. He didn’t make pilot, but he got his commission as a navigator and was assigned to a B-17 crew in England.”

Ingram took out one of his remaining two cigars and lighted it. The pieces were beginning to fit together now, and he was pretty sure he knew why Ruiz was going over the hill. A little shiver ran up his back, and he hunched his shoulders against the darkness behind him. He told her about Ruiz’ visit.

“Those boys are running from something really bad. I should have figured it out in the beginning, from the way Morrison acted. He’d rather risk anything than go back to Florida. But it was hard to see because as far as we know they hadn’t killed anybody, and hadn’t planned to. In fact, they’d gone to considerable trouble to get old Tango out of the way without hurting him—”

Rae Osborne broke in. “But somewhere along the line they did kill somebody.”

“They must have.”

“Patrick Ives,” she said excitedly. “Why didn’t we see it before? The body was here near the Dragoon, but the dinghy was picked up over twenty miles away, in deep water.”

“That’s perfectly natural,” Ingram pointed out. “The body was submerged—and probably on the bottom—a good part of the time, so it was acted on only by the tides. But the dinghy was carried off to the westward by the wind and the sea.”

“Yes, but look, Captain—Don’t you see? That’s the reason Morrison wouldn’t let anybody go out and get his body when Avery saw it from the plane and called us on the radio. We’d find out Ives hadn’t drowned at all, that he’d been killed.”

“No,” Ingram said. “If Morrison had had five years to work on it, he couldn’t have dreamed up a story that matched the evidence as perfectly as that did. I was already pretty sure the man had drowned, even before I got aboard the Dragoon, and I don’t have any doubt at all it happened exactly the way Morrison said it did. What he didn’t want us to find out was that the man wasn’t Ives.”

“What?”

“I don’t think Ives was even aboard when they left Florida.”

“But he had to be. The watch—”

“This other man, whoever he was, must have been wearing the watch. That’s all. I don’t know whether Ives is the one who’s been murdered, but somebody was, and it happened ashore where it can be proved, not out here where it could be covered up as an accidental drowning. Naturally, Morrison wasn’t going to tell us about it as long as he had a perfectly good ready-made explanation for Ives’ being missing. He was going to have his hands full as it was, forcing me to take them down there and watching us so we didn’t escape. If we knew the real story, we’d jump overboard and try to swim back to Miami.”

“He intends to kill us, then, when we get to this Bahia San Felipe?”

“I think so. And Ruiz can’t quite hold still for anything as cold-blooded as that, so he’s about made up his mind to pull out. If he can.”

“I see,” she said. She was silent for a moment, and then she asked, “You’re absolutely certain there was another man?”

“There has to be.” He scooped up the black plastic box and showed her the contents, and told her about the compass.

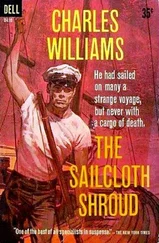

“That’s the reason they got in here over the Bank and ran aground. They’ve been lost. Remember, they stole the Dragoon on Monday night, so it couldn’t have been any later than Wednesday night when they loaded the guns down in the Keys, and sailed. This isn’t over a day’s run from anywhere in the Keys, because even if it’d been calm they would have used the engine, but they didn’t go aground here until Saturday night. So for at least two days they’ve been wandering around like blind men because the compass is completely butched up by all that steel—those gun barrels. Even if one of them knew how to use the radio direction finder well enough to get a fix by cross-bearings, it’s no good unless you’ve got a compass. Here’s what happens—say they get a fix from the RDF, figure out the compass course to where they want to go, and then after a while they check their position again, and find out they’ve gone at maybe right angles to where they thought they were heading. So obviously the first position must have been wrong. Or was it the second position? Do that about three times, and you’re so hopelessly lost you wouldn’t bet you’re in the right ocean.”

“But,” she said, “didn’t Ruiz say they knew about the steel’s effect? And that Ives had checked the error before they left?”

“Sure,” Ingram replied. “On one heading. That’s what gave it away—I mean, that he’d already disappeared even before they sailed. It couldn’t have been Ives who did that. He’d have known better. Admittedly, he could have got pretty rusty in fifteen years, and the compasses on those planes were probably gyros, but nobody who’d ever studied navigation could know that little about magnetic compasses. They’re basic, like the circulation of the blood to the study of medicine. And you don’t adjust one by finding out what the error is on one heading and then applying that same correction all the way around. It’s different in every quadrant, so you have to check it in every quadrant. Actually, on some headings, what they were doing was multiplying the error instead of correcting it.”

“Then I guess there’s no doubt,” she said. “But if somebody’s been killed, why do you suppose the police didn’t say anything about it?”

“They don’t always tell you everything they know. And maybe they don’t know, or don’t have any reason yet to connect it with the theft of the Dragoon.”

“Yes, that’s possible.” She flipped her cigarette away in the darkness. “If we could surprise Ruiz and get that gun away from him while Morrison’s over here, could we make it ashore in the raft?”

Читать дальше