“Hi again,” she said. “I didn’t think you’d mind if I let myself in.”

“No, not at all.”

“My flight landed early and I needed to go over some things with you, and while I was waiting I thought I’d freshen up.”

“Really, it’s fine. I don’t exactly feel like I’m alone in this place anyway, if you know what I mean.” He held up the frozen-food tray in his hand. “Would you like some delicious low-sodium, gluten-free dinner?”

“That would actually be pretty good. I forgot to eat much today.” She finished with her towel, ran her fingers through her hair a couple of times, and somehow ended up looking like she’d just spent half an hour in front of the mirror. “This is a nice place you’ve got.”

“Do I have it, or does it have me?”

“You really shouldn’t complain, if you think about it.”

“I know. My father must have laid on the pressure, for the job and to land this place for me. I’m still not sure why he did that, but no, I’m not complaining.”

“I’ll tell you what,” she said. “You put dinner in the microwave, I’ll get dressed, and we’ll get started on what we need to do, okay?”

“Good.”

She returned just as the oven beeped to indicate their food was finished. He pulled out a chair for her but she chose another, one facing the door.

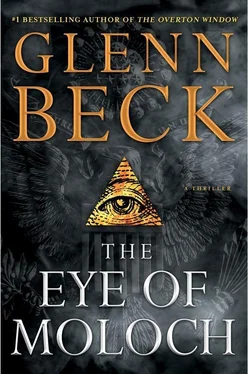

They talked as they ate, a little about Molly, but mostly about other things. As they reached their bland dessert Virginia asked him about his new job.

“It’s strange,” Noah said. “There are only three of us: me, an elderly man, and a young woman. Just a girl, really.”

“What do you do, the three of you?”

“That’s the strange part. It’s busywork, mostly, although I did sharpen up some talking points for the White House press secretary in the afternoon. I feel sorry for this poor guy they’ve got in there now; it’s like they’re not even trying anymore.”

“And what about the other two, your new colleagues?”

“The old fellow used to be on the news but it sounds like he didn’t change with the industry, and so the industry pushed him out.”

Virginia smiled. “Way out, by the look of it.”

“Yeah, to hear him tell it he’s made some powerful enemies, probably like everyone else here on our side of the bars. Whoever’s running this show, they give him about one story a week to write, and that’s probably just so they can keep an eye on him and make sure he’s toeing the line. He spends the rest of his time writing fillers for syndication.”

“Fillers?”

“Little blurbs to finish out a short column on the back pages of the paper. News people use them, too, and disc jockeys. Those random anecdotes you hear sometimes, ‘did you know?’–type items, fascinating facts, stuff like that.”

“What about the girl?”

“Lana doesn’t say much but she’s got some real talent. She mostly works at stirring up trouble on the blogs, starting comment wars on social news sites, that sort of thing.”

“What’s the value of that?”

“Are you kidding? These days it’s enormously valuable. With everyone so connected it’s the best place to mess with public opinion. Even though it’s all anonymous, people seem to think they’re just talking to a group of friends. Probably nine out of ten of the user comments you read on some of those sites are bought and paid for like that.”

“Nine out of ten?”

“Sometimes ninety-nine out of a hundred, and I’m not even exaggerating.”

“And all these fake opinions accomplish what?”

“Come on, you know better than I do. The CIA spends eighty-five percent of its budget on psychological manipulation.”

“I’ve always managed to keep myself in the better fifteen percent.”

“Here’s the basic idea. You take an issue, present a strong and reasonable argument for both sides of the question, and then you proceed to belittle anyone who falls outside the two groups. Do that, and you’ve done a couple of things. First, you’ve divided a lot of the readers cleanly into two controllable factions, and implanted an easy-to-digest opinion that they’ll repeat: liberal or conservative, Democrat or Republican, whatever. Second, you’ve made it seem to the undecided majority that there’s really no right answer, no real choice. You make them feel like outsiders who don’t belong, and that makes them more likely to shut up and stay at home drowning their sorrows on election day. You make thinking for yourself seem uncool and socially unacceptable, and nobody wants to be part of that.”

“So that’s all she does all day? She writes fake comments?”

“You make it sound easy but it really takes a lot of finesse to do it right. I looked over her shoulder once today and she was actually in a full-out argument with herself. Both sides had thousands of up-votes from the onlookers. Her real specialty is Trotskying, though.”

“Trotskying? And what’s that?”

“It’s the visual form of content-scrubbing. She downloads photographs and videos from the archives, removes or changes things in Photoshop and other tools, and then she re-uploads the new material. It’s what Lenin did to Trotsky after they had a falling-out; he tried to erase him from history, that’s how the practice got its name. Only it’s much faster now, and a lot more permanent.”

“And that works?”

“She single-handedly helped the press squeeze a third-party presidential candidate out of the race over the last few months. He was actually getting popular for a while, raising some sticky issues for the front-runners, and now it’s like he was never even there.”

“There are so many channels available,” Virginia said, “so many radio stations and newspapers and magazines. It just seems like it should be harder to control what we’re seeing than you make it sound.”

“It should be, but it’s not. You’ve got to remember, only six corporations control almost all of the media outlets today. It was about ninety companies when I was born, now it’s six. They don’t have to corral three hundred million viewers, just three hundred executives, and they were all in my old Rolodex when I worked in New York. And it’s not getting any better. Rumor has it, up at the very top the ownership’s being consolidated down to only one.”

As the meal continued the conversation shifted, thankfully, to topics other than his work. The interaction seemed genuinely friendly; Noah never got the feeling that she was working him like an informant, though in her own charming way she obviously was. In any case he felt comfortable with her, and he needed that.

“Do I know you well enough now to ask you how you lost your leg?”

“In the war,” she replied, not bothering to tell him which one. “I was on my seventh tour, we were on our way back from a major engagement in Sadr City, an incredible meat grinder. It was street fighting, no time to think or plan, both sides just going at it for days. When it was over my detachment got out with no casualties; it was like a miracle, no one had a scratch. Then the convoy got hit by a string of IEDs on the road back to the base. We lost five, and that’s how I lost my leg.”

“Seven tours,” he said. “Was that by choice?”

She nodded.

“Why did you keep going back?”

“Because my brothers and sisters were there, and we all took the same oath, and I couldn’t see leaving them until the job was done.” She seemed to become more thoughtful, as though her answer had left something important unexplained. “War is a terrible thing, but once we’ve made the careful and honest decision to send our volunteers out into it, once we’ve committed the blood of the best of us, we need to give them a clear goal and the full permission to win. And then when they’ve done that, we need to bring them on home.”

Читать дальше