• • •

A bevy of nurses on constant call would aid him if required but he’d vowed to himself that he would stand and walk on his own through all but the most trying days.

After swallowing the line of pills and arcane tinctures arranged as always on his bedside table, he set his jaw, took up his cane, and readied himself to rise again. With some effort he sat upright, endured a wave of dizziness and let it pass on through, and then left his bed and stood upon the smooth, cool floor.

As was his custom, while still in pajamas he took his morning inventory of the most treasured things in his surroundings. All were priceless and quite irreplaceable, but more important, they were reminders.

The veined white marble beneath his feet was harvested from the towering halls once walked by the pharaohs of Egypt. For a period far longer than the upstart reign of Christendom their subjects believed these earthbound rulers to be divine, and they might as well have been; their unbroken dominion spanned forty centuries.

The Great Pyramid had been as old and mysterious to Cleopatra as her own time is to the present day; the very apex of its long-lost capstone, nearly half a ton of inlaid gold and alabaster, was now the cornerstone of his décor in the grand foyer.

An Irish temple nestled near a bend on the River Boyne was older still, older than Stonehenge by a millennium and once a place of pagan worship in the cult of Baal. Its stolen altar now graced his western balcony, where he often sat to reflect with his afternoon tea.

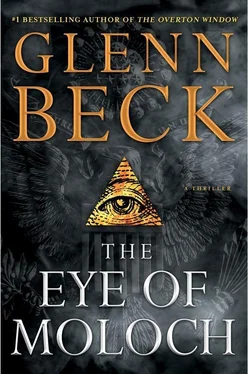

A heavy faceted orb of purest emerald, whose aspect suggested a great unblinking eye, was set above the granite hearth in his study. This priceless, cursed stone had been taken in the spoils of some ancient war, chipped from the face of a great graven image of Moloch once worshiped by the high priests of Sidon. It was a symbol now of an awesome power that technology was fast delivering into his waiting hands. The myriad human sacrifices this eye had overseen would be dwarfed by those in the terrible, cleansing carnage soon to come.

Even the wood in his walking stick spoke an encouraging whisper from the ages. It was turned from the trunk of a precious Norway spruce that had lived and grown on the side of a mountain in Sweden for nearly ten thousand years. When this oldest of trees was only a seedling, the polished stone ax was still the pinnacle of human invention.

In the presence of such things his own age seemed less daunting, his enemies less formidable, and the completion of his lifelong project somehow nearer at hand. These things helped him remember that on the long timeline of history, the United States of America had managed to survive for barely an instant. And its last days were numbered; that failing experiment was the only remaining barrier that stood between Aaron Doyle and the realization of his dream.

And then, in his private study he came to the centerpiece of his home. This, a twelfth-century chessboard with pieces carved from walrus ivory, was the arena where he had once spent many an hour matching wits with his philosophical rival, William Merchant. Those early bitter contests had often ended in a draw, but now the real-world game was finally about to be won.

Though the two men had been estranged for many years, once this was all over Doyle had always hoped they might meet again. To that end, two comfortable chairs were placed on either side and the old board was set up for a last match, should the day of their reunion ever come.

• • •

When he returned to the bedroom he dressed himself in simple clothes; years before he’d chosen comfort over style when there was no one left above him to impress. A fetching young lady in a plain uniform appeared to do his zippers, clasps, and buttons. She left a tray of fresh juices for his breakfast, her pretty eyes averted all the while, and promptly vanished again.

With his morning pains eased somewhat after the walk, now dressed, fed, and medicated he felt ready for the day’s agenda to begin.

His lingering storm would be causing havoc with the rush-hour commuters scuttling far below; it was still much easier for science to make it rain than to make it stop again. Despite the snarled traffic, however, he was pleased to see that his first appointment had already arrived and was waiting in the sunroom. He was standing by the windows, taking in his first view of the Persian Gulf from the dizzying heights of the Burj Khalifa.

His guest turned to face him as he walked up close beside. He seemed utterly tongue-tied at the sudden sight of his reclusive host, a man he’d no doubt heard described only in the folklore of his cutthroat profession. At length it fell to the elder man to break the reverent silence that hung between them.

“At last we meet in person,” he said, extending his fragile hand. “Mr. Warren Landers, I’m Aaron Doyle.”

• • •

Landers reported that the muscle was now in place for the upcoming structured chaos to be unleashed on American soil. The decaying European Union, the ever-volatile Middle East, the chaos pillaging Africa, the powder kegs of central and southern Asia—in those regions the downward spirals Aaron Doyle had also fostered were already building momentum past the point of no return. Soon, as their own nations fell toward ruin all eyes would turn to the United States, and they would see then that the mythic soul of this last citadel of hope and freedom was as empty and diseased as all the rest.

“You’ve done good work,” Doyle said.

“Thank you, sir.”

“But you must be wondering why I asked you to come here and discuss these matters with me. In the past I’ve always dealt only with Arthur Gardner, so it seems I’ve put you in an awkward position. You’ve now gone over the head of your employer, or behind his back as the case may be.”

“I trust your judgment,” Landers said, “and I do have a sense of why I’m here.”

“He has changed, hasn’t he, of late? Then it isn’t my imagination. You know, I have an old adversary in this campaign, and in the past he’s occasionally turned the hearts of my best generals to his side of the cause, and I’ve done the same to him. But with Arthur I believe it’s different. He couldn’t be bought with any offer of money or power, but he’s been vulnerable in another way. After all I’d invested in him, I once nearly lost him to the love of a common woman. And now I fear I may be losing him to a late-blooming love for his only son.”

Landers nodded, looking appropriately concerned. Despite the nearly authentic expression of solemn regret on his face, there was also an undercurrent there that could best be described as anticipation.

“Now then, before we enjoy our brunch,” Aaron Doyle said, “let us discuss how we shall finally bring the brief and teetering empire of the United States of America to an unceremonious close. And on a related subject, tell me everything you know about this little troublemaker, Molly Ross, and the possibly useful bond she still maintains with our young man, Noah Gardner.”

Chapter 19

You Can Lead a Horse to Slaughter,

but You Can’t Make Him Think

or

How I Spent My 16th Birthday

by Noah W. Gardner

Period 7, Mrs. Schantz

3/21/1997

Honors English

Introduction

How are a modern slaughterhouse and the field of public relations alike?

Last year, when a group of investors set out to build a new kind of meat-processing plant—far bigger and more efficient than ever—they didn’t go to an architect, or a stockman, or any general contractor experienced in the field. Instead they hired the world’s preeminent social engineer. So on my 16th birthday they came to 500 Fifth Avenue in New York City, and they sat down with my father, Arthur Gardner.

Читать дальше