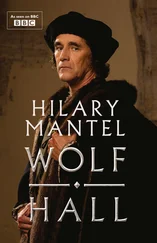

Hilary Mantel - Wolf Hall - Bring Up the Bodies

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Hilary Mantel - Wolf Hall - Bring Up the Bodies» — ознакомительный отрывок электронной книги совершенно бесплатно, а после прочтения отрывка купить полную версию. В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Жанр: Старинная литература, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Wolf Hall: Bring Up the Bodies

- Автор:

- Жанр:

- Год:неизвестен

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:5 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Wolf Hall: Bring Up the Bodies: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Wolf Hall: Bring Up the Bodies»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

Wolf Hall: Bring Up the Bodies — читать онлайн ознакомительный отрывок

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Wolf Hall: Bring Up the Bodies», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

Jane is facing front, like a sentry. The clouds have blown away overnight. We may have one more fine day. The early sun touches the fields, rosy. Night vapours disperse. The forms of trees swim into particularity. The house is waking up. Unstalled horses tread and whinny. A back door slams. Footsteps creak above them. Jane hardly seems to breathe. No rise and fall discernible, of that flat bosom. He feels he should walk backwards, withdraw, fade back into the night, and leave her here in the moment she occupies: looking out into England.

II

Crows

LONDON AND KIMBOLTON, AUTUMN 1535

Stephen Gardiner! Coming in as he’s going out, striding towards the king’s chamber, a folio under one arm, the other flailing the air. Gardiner, Bishop of Winchester: blowing up like a thunderstorm, when for once we have a fine day.

When Stephen comes into a room, the furnishings shrink from him. Chairs scuttle backwards. Joint-stools flatten themselves like pissing bitches. The woollen Bible figures in the king’s tapestries lift their hands to cover their ears.

At court you might expect him. Anticipate him. But here? While we are still hunting through the countryside and (notionally) taking our ease? ‘This is a pleasure, my lord bishop,’ he says. ‘It does my heart good to see you looking so well. The court will progress to Winchester shortly, and I did not think to enjoy your company before that.’

‘I have stolen a march on you, Cromwell.’

‘Are we at war?’

The bishop’s face says, you know we are. ‘It was you who had me banished.’

‘I? Never think it, Stephen. I have missed you every day. Besides, not banished. Rusticated.’

Gardiner licks his lips. ‘You will see how I have spent my time in the country.’

When Gardiner lost the post of Mr Secretary – and lost it to him, Cromwell – it had been impressed on the bishop that a spell in his own diocese of Winchester might be advisable, for he had too often cut across the king and his second wife. As he had put it, ‘My lord of Winchester, a considered statement on the king’s supremacy might be welcome, just so that there can be no mistake about your loyalty. A firm declaration that he is head of the English church and, rightfully considered, always has been. An assertion, firmly stated, that the Pope is a foreign prince with no jurisdiction here. A written sermon, perhaps, or an open letter. To clear up any ambiguities in your opinions. To give a lead to other churchmen, and to disabuse ambassador Chapuys of the notion that you have been bought by the Emperor. You should make a statement to the whole of Christendom. In fact, why don’t you go back to your diocese and write a book?’

Now here is Gardiner, patting a manuscript as if it were the cheek of a plump baby: ‘The king will be pleased to read this. I have called it, Of True Obedience .’

‘You had better let me see it before it goes to the printer.’

‘The king himself will expound it to you. It shows why oaths to the papacy are of none effect, yet our oath to the king, as head of the church, is good. It emphasises most strongly that a king’s authority is divine, and descends to him directly from God.’

‘And not from a pope.’

‘In no wise from a pope; it descends from God without intermediary, and it does not flow upwards from his subjects, as you once stated to him.’

‘Did I? Flow upwards? There seems a difficulty there.’

‘You brought the king a book to that effect, the book of Marsiglio of Padua, his forty-two articles. The king says you belaboured him with them till his head ached.’

‘I should have made the matter shorter,’ he says, smiling. ‘In practice, Stephen, upwards, downwards – it hardly matters. “Where the word of a king is, there is power, and who may say to him, what doest thou?”’

‘Henry is not a tyrant,’ Gardiner says stiffly. ‘I rebut any notion that his regime is not lawfully grounded. If I were king, I would wish my authority to be legitimate wholly, to be respected universally and, if questioned, stoutly defended. Would not you?’

‘If I were king…’

He was going to say, if I were king I’d defenestrate you. Gardiner says, ‘Why are you looking out of the window?’

He smiles absently. ‘I wonder what Thomas More would say to your book?’

‘Oh, he would much mislike it, but for his opinion I do not give a fig,’ the bishop says heartily, ‘since his brain was eaten out by kites, and his skull made a relic his daughter worships on her knees. Why did you let her take the head off London Bridge?’

‘You know me, Stephen. The fluid of benevolence flows through my veins and sometimes overspills. But look, if you are so proud of your book, perhaps you should spend more time writing in the country?’

Gardiner scowls. ‘You should write a book yourself. That would be something to see. You with your dog Latin and your little bit of Greek.’

‘I would write it in English,’ he says. ‘A good language for all sorts of matters. Go in, Stephen, don’t keep the king waiting. You will find him in a good humour. Harry Norris is with him today. Francis Weston.’

‘Oh, that chattering coxcomb,’ Stephen says. He makes a cuffing motion. ‘Thank you for the intelligence.’

Does the phantom-self of Weston feel the slap? A gust of laughter sweeps out from Henry’s rooms.

The fine weather did not much outlast their stay at Wolf Hall. They had hardly left the Savernake forest when they were enveloped in wet mist. In England it’s been raining, more or less, for a decade, and the harvest will be poor again. The price of wheat is forecast to rise to twenty shillings a quarter. So what will the labourer do this winter, the man who earns five or six pence a day? The profiteers have moved in already, not just on the Isle of Thanet, but through the shires. His men are on their tail.

It used to surprise the cardinal, that one Englishman would starve another and take the profit. But he would say, ‘I have seen an English mercenary cut the throat of his comrade, and pull his blanket from under him while he’s still twitching, and go through his pack and pocket a holy medal along with his money.’

‘Ah, but he was a hired killer,’ the cardinal would say. ‘Such men have no soul to lose. But most Englishmen fear God.’

‘The Italians think not. They say the road between England and Hell is worn bare from treading feet, and runs downhill all the way.’

Daily he ponders the mystery of his countrymen. He has seen killers, yes; but he has seen a hungry soldier give away a loaf to a woman, a woman who is nothing to him, and turn away with a shrug. It is better not to try people, not to force them to desperation. Make them prosper; out of superfluity, they will be generous. Full bellies breed gentle manners. The pinch of famine makes monsters.

When, some days after his meeting with Stephen Gardiner, the travelling court had reached Winchester, new bishops had been consecrated in the cathedral. ‘My bishops’, Anne called them: gospellers, reformers, men who see Anne as an opportunity. Who would have thought Hugh Latimer would be a bishop? You would rather have predicted he would be burned, shrivelled at Smithfield with the gospel in his mouth. But then, who would have thought that Thomas Cromwell would be anything at all? When Wolsey fell, you might have thought that as Wolsey’s servant he was ruined. When his wife and daughters died, you might have thought his loss would kill him. But Henry has turned to him; Henry has sworn him in; Henry has put his time at his disposal and said, come, Master Cromwell, take my arm: through courtyards and throne rooms, his path in life is now made smooth and clear. As a young man he was always shouldering his way through crowds, pushing to the front to see the spectacle. But now crowds scatter as he walks through Westminster or the precincts of any of the king’s palaces. Since he was sworn councillor, trestles and packing cases and loose dogs are swept from his path. Women still their whispering and tug down their sleeves and settle their rings on their fingers, since he was named Master of the Rolls. Kitchen debris and clerks’ clutter and the footstools of the lowly are kicked into corners and out of sight, now that he is Master Secretary to the king. And no one except Stephen Gardiner corrects his Greek; not now he is Chancellor of Cambridge University.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Wolf Hall: Bring Up the Bodies»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Wolf Hall: Bring Up the Bodies» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Wolf Hall: Bring Up the Bodies» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.