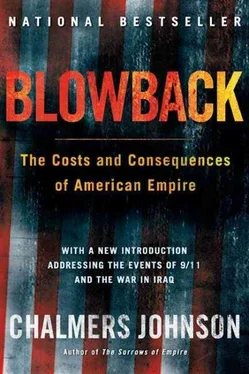

Chalmers Johnson - Blowback, Second Edition - The Costs and Consequences of American Empire

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Chalmers Johnson - Blowback, Second Edition - The Costs and Consequences of American Empire» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 0101, ISBN: 0101, Издательство: Macmillan, Жанр: Старинная литература, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Blowback, Second Edition: The Costs and Consequences of American Empire

- Автор:

- Издательство:Macmillan

- Жанр:

- Год:0101

- ISBN:9780805075595

- Рейтинг книги:5 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Blowback, Second Edition: The Costs and Consequences of American Empire: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Blowback, Second Edition: The Costs and Consequences of American Empire»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

Blowback, Second Edition: The Costs and Consequences of American Empire — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Blowback, Second Edition: The Costs and Consequences of American Empire», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

Once the high yen–low dollar regime was in place, the U.S. government assumed that the trade imbalance would correct itself. The United States did nothing to end Japan’s barriers against imports and still permitted Japan to export into its market anything and everything it could sell there. Japan reacted to the high yen by putting its industrial policy system into high gear in order to lower costs so it could continue its export-led growth, even at a disadvantageously high exchange rate. The Japanese Ministry of Finance also lowered domestic interest rates to make capital virtually free and encouraged industrial groups to invest more vigorously than they had ever done before. The result was fantastic industrial overcapacity and a “bubble economy,” in which the prices of such things as real estate lost any relationship to underlying values. Business leaders proudly announced on American television that a square meter of the Ginza was worth more than all of Seattle. Ultimately, huge debts accumulated and the Japanese banks were stuck with at least $600 billion in “nonperforming” loans that threatened to bankrupt the entire banking system.

By 1995, the contradictions were starting to come to a head. Japan still had a huge surplus of savings, which it exported to the United States by investing in U.S. Treasury bonds, thereby helping fund America’s debts and keep its domestic interest rates low. And yet Japan itself was simultaneously facing the possibility of the collapse of several of its bankrupt banks. Financial leaders said to the Americans that they needed relief from the high yen in order to increase Japan’s exports. They hoped to solve their problems in the traditional way, via more export-led growth. Eisuke Sakakibara, then Japan’s vice minister for international affairs in the Ministry of Finance, readily acknowledges that he intervened with Washington to lower the value of the yen and admits to his “inadvertent role in precipitating one of the 20th century’s greatest economic crises.” 6The United States went along with this; facing reelection in 1996, Bill Clinton certainly did not want Japanese capital called home to prop up Japanese banks at that moment. As a result, between 1995 and 1997 the U.S. Treasury and the Bank of Japan engineered a “reverse Plaza Accord”—which led to a 60 percent fall of the yen against the dollar.

However, in the wake of the Plaza Accord, many newly developing Southeast Asian economies had by then “pegged” their currencies to the low dollar, establishing official rates at which businesses and countries around the world could exchange Southeast Asian currencies for dollars. So long as the dollar remained cheap, this gave them a price advantage over competitors, including Japan, and made the region very attractive to foreign investors because of its rapidly expanding exports. It also encouraged reckless lending by domestic banks, since pegged exchange rates seemed to protect them from the unpredictability of currency fluctuations. During the early 1990s, all of the East Asian countries other than Japan grew at explosive rates. Then the “reverse Plaza Accord” brought disaster. Suddenly, their exports became far more expensive than Japan’s. Export growth in second-tier countries like South Korea, Thailand, Indonesia, Malaysia, and the Philippines went from 30 percent a year in early 1995 to zero by mid-1996. 7

Certain developments in the advanced industrial democracies only compounded these problems. Some of their capitalists had spent the post–Plaza Accord decade developing “financial instruments” that enabled them to bet on whether global currencies would rise or fall. They had also accumulated huge pools of capital, partly because aging populations led to the exceptional growth of pension funds, which had to be invested somewhere. Mutual funds within the United States alone grew from about $1 trillion in the early 1980s to $4.5 trillion by the mid-1990s. These massive pools of capital could have catastrophic effects on the value of a foreign currency if transferred in and then suddenly out of a target country. Fast-developing computer and telecommunications technologies radically lowered transaction costs while increasing the speed and precision with which finance capitalists could transfer money and manipulate currencies on a global scale. The managers who controlled these funds began to encourage investment anywhere on earth under the rubric of “globalization,” an esoteric term for what in the nineteenth century was simply called imperialism. They argued that excess capital should be allowed to flow freely in and out of any and all countries. Some economists argued that the free flow of capital was the same thing as the free flow of goods, despite mountainous evidence to the contrary.

Capital flows to developing nations in Asia and Latin America jumped from about $50 billion a year before the end of the Cold War to $300 billion a year by the mid-1990s. From 1992 to 1996, Indonesia, Malaysia, Thailand, and the Philippines experienced money and credit growth rates of 25 percent to 30 percent a year. During this same period South Korea, Thailand, and Indonesia invested nearly 40 percent of their gross domestic product in new productive capacity as well as in hotels and office buildings; the comparable figure for European nations was only 20 percent and even less for the United States. In 1996, Asia was the destination for half of all global foreign investment, European and Japanese as well as American. On the American side, by 1997 Citibank held about $22 billion in local currency loans in East Asia, about $20 billion in securities, and $8 billion in dollar loans; Morgan Bank had $19 billion in Asian securities and $6 billion in dollar loans; and Chase had $4 billion in local currency loans, $15 billion in Asian securities, and $6 billion in dollar loans. 8

Although they did not speak out at the time, a number of famous financiers and economists have since pointed out the dangers of what is called “hot money” or “gypsy capital.” George Soros, one of the world’s richest financiers and head of a large “hedge fund” located in the Netherlands Antilles, asserted that “financial markets, far from tending toward equilibrium, are inherently unstable,” and he warned against the folly of continuing down the path of deregulating the financial services industry. 9Jagdish Bhagwati, one of free trade’s most passionate supporters and a former adviser to the director-general of the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade, argued that the idea of free trade had been “hijacked by the proponents of capital mobility.” He claimed that there was a new “Wall Street–Treasury complex,” comparable to the military-industrial complex, which contributes little to the global economy but profits enormously from pretending that it does. The East Asian economies did not really need hot money from abroad, since in most cases they saved enough themselves to finance their own growth. Bhagwati has also pointed out that an unregulated financial system can with relative ease become divorced from the productive system it is supposed to serve and so be unnaturally predisposed to “panics and manias.” 10

There was as well a less financial ingredient in the disaster-in-the-making. Without particularly thinking about it or sponsoring any public debate on the subject, the U.S. government built its future global policies on the main military elements of its Cold War policies. It expanded NATO to include the former Soviet satellites of the Czech Republic, Hungary, and Poland; it reinforced its East Asian alliances; and it committed itself to ensuring access to Persian Gulf oil for itself and its allies. The Gulf War of 1991 was the first demonstration of this commitment. Eschewing a “peace dividend,” which it might have directed toward its own industrial and social infrastructure, the United States also kept its Cold War–sized defense budgets in the $270 billion range while seeking to reorient its military focus from the possibility of war with a more or less equivalent enemy to imperial policing chores everywhere on earth.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Blowback, Second Edition: The Costs and Consequences of American Empire»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Blowback, Second Edition: The Costs and Consequences of American Empire» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Blowback, Second Edition: The Costs and Consequences of American Empire» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.