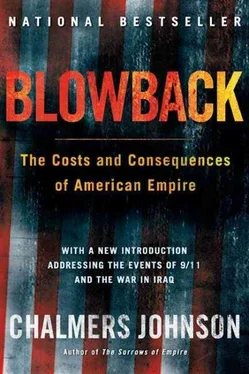

Chalmers Johnson - Blowback, Second Edition - The Costs and Consequences of American Empire

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Chalmers Johnson - Blowback, Second Edition - The Costs and Consequences of American Empire» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 0101, ISBN: 0101, Издательство: Macmillan, Жанр: Старинная литература, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Blowback, Second Edition: The Costs and Consequences of American Empire

- Автор:

- Издательство:Macmillan

- Жанр:

- Год:0101

- ISBN:9780805075595

- Рейтинг книги:5 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Blowback, Second Edition: The Costs and Consequences of American Empire: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Blowback, Second Edition: The Costs and Consequences of American Empire»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

Blowback, Second Edition: The Costs and Consequences of American Empire — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Blowback, Second Edition: The Costs and Consequences of American Empire», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

These American assumptions were almost identical to the Soviet assumption that the institutions of “socialism” must be those that existed in the USSR during, say, the Khrushchev era. Neither side ever produced an ideological model to sell to others that could be divorced from their own country. Because of this inability to express the institutions of either socialism or capitalism in some culturally neutral—or at least more varied—way, it is understandable that many observers simply reduced the claims of Marxist-Leninist ideology to the USSR and those of free-market capitalism to the United States.

In finding a third way, Japan’s postwar economic “miracle” reinvented not economic theory but the institutions of modern capitalism so that they would produce utterly different outcomes from those imagined in the American model. Given Japan’s history of catch-up industrialization, its overarching need to avoid the victimization and colonialism to which every other area of East Asia had succumbed, its virtual dearth of raw materials, its dependence on manufacturing and international trade to sustain its large population, and its overwhelming defeat in World War II, it could not ever have become a clone of the United States. Its postwar planners and technocrats instead organized a capitalist economy intended to serve the interests of producers over consumers. They forced Japan’s citizens to save by providing little in the way of a safety net; they encouraged labor harmony regardless of what it did to individual rights; and they built industries based on the highest possible human input rather than simply on some naturally given comparative advantage, such as cheap labor or proximity to a large market like China’s. Their goal was to enrich Japan, if not necessarily the Japanese themselves. They viewed all economic transactions as strategic: theirs was to be an economy organized for war but now directed toward ostensibly peaceful competition with other countries.

Since the 1950s, the United States had seen the entire world in Cold War terms. This meant that Japan was far more important as an anti-Communist ally than as a potential economic competitor. In order to keep U.S. troops and bases in Japan, the Americans provided open access to their market and the government pressured private American firms to relinquish ownership rights to technologies being transferred to Japan. As Japanese trade and industrial bureaucrats took advantage of this deal, trade disputes became inevitable. From the “dollar blouses” that flooded into the United States during the Eisenhower era to the textile disputes of the Kennedy and Nixon administrations, complaints about the costs of “alliance” with Japan became a permanent feature of Washington politics. They also produced a lucrative new field for former government officials turned lobbyists, whom the Japanese hired in increasing numbers to ameliorate or paper over the disputes. Even though Washington remained more or less ignorant of how the government in Tokyo actually worked, the government in Tokyo took a life-or-death interest in Washington’s role in regulating the American economy. Japanese officials also did everything in their power to maintain the artificial separation between trade and defense that the U.S. government had invented and to see that the Pentagon was happy with its facilities.

This artificial separation between trade and defense has been a peculiar characteristic of the half-century-long American hegemony over Japan. Official guardians of the Japanese-American Security Treaty and their academic supporters have maintained an impenetrable firewall between what they call, using the Japanese euphemism, “trade friction” and the basing of one hundred thousand American troops in Japan and South Korea. There was no reason why these two aspects of the Japanese-American relationship should been dealt with as if they were separate matters except that, had they not been, the actual nature of the relationship would have been far easier to grasp.

Until the 1980s, the United States officially ignored all evidence that this compartmentalization of its massive military establishment and its growing trade deficits with Japan was going to be very costly. From about 1968 on, trade deficits began to rise just as the hollowing out of certain industries that the Japanese government had targeted became more visible. U.S. officials then consulted with their Japanese counterparts about these problems and accepted fig-leaf agreements that offered the pretense of remedies to distressed American businesses and communities. With the exception of President Nixon’s 1971 decision to force an ending to Japan’s artificially undervalued exchange, nothing else of significance was done.

During the 1980s, however, pressures for action of some sort markedly increased. The Japanese economy, now a major competitor, was starting to erode the industrial foundations of the United States. Moreover, the Cold War was settling into its final Reaganesque rituals. Despite inflated CIA estimates of Soviet strength, it became increasingly clear to many, even before the rise to power of Mikhail Gorbachev, that the two sides were starting to accommodate each other and that the threat of a superpower war was declining. In this context, a new way of thinking developed about Japan itself and about the nature of America’s relationships with newly rich Asia. Business Week dubbed it “revisionism” and wrote:

No less than a fundamental rethinking of Japan is now under way at the highest levels of the U.S. government, business, and academia. The standard rules of the free market, according to the new school, simply won’t work in Japan. . . . Some people call the new thinking “revisionism,” departing as it does from the orthodox view that Japan will eventually become a U.S.-style consumer-driven society. 4

The Japanese, who had been very proud of their “developmental state” and its guided economy and who readily wrote about it for domestic consumption, suddenly became concerned when American revisionists, myself included, began saying that “leveling the playing field” was not the issue, since the two economies were different in such fundamental ways. It was one thing for Japan and its lobbyists to parry complaints about their country’s closed markets and the numerous barriers it raised against foreign products ranging from automobiles and semiconductors to grapefruit and rice. It was quite another for Americans to claim that they were playing by entirely different rules. Accusations that the “revisionists” were Japan bashers or racists rose quickly to the surface.

Meanwhile, a number of Japanese politicians and industrialists added insult to injury by claiming that the trade deficit resulted from the laziness of American workers or resorted to racism by pointing to the racially mixed nature of the workforce while characterizing American minorities as indisciplined and ineducable. In 1989, a prominent Japanese politician, Shintaro Ishihara, and the president of Sony, Akio Morita, cowrote a book, The Japan That Can Say “No,” in which they suggested that their country should not share Japanese-developed technologies that the Americans regarded as of national security significance unless the Americans reined in their critiques. In 1998, Ishihara, angry about an economy that seemed to be heading into decline, wrote a sequel, The Japan That Can Say “No” Again , suggesting a halt in investment in U.S. government securities to teach a lesson to Americans who had pushed Japan to open its economy. These views made him sufficiently popular that in 1999 he was elected mayor of Tokyo.

Nonetheless, the American government continued its typical Cold War style of doing business into the early 1990s. In 1988, for example, State Department and Pentagon leaders proposed transferring to Japan the technology of the F-16 fighter aircraft in order to allow the Japanese to build their own fighter, the FS-X. A huge controversy erupted over why the Japanese did not simply buy the F-16 fighters they needed from the manufacturer, thereby helping to balance the trade deficit and keep manufacturing in the United States. One State Department official, Kevin Kearns, who was in Tokyo at the time the FSX deal was negotiated, agreed with the critics and wrote in the Foreign Service Journal , “As long as the Chrysanthemum Club [of pro-Japanese American officials] continues to skew the policy process in our government and paid Japanese lobbyists and academics-for-hire continue to influence disproportionately the treatment of Japan in the public realm, the United States will continue its approach to Japan in the same tired, self-defeating way.” 5Following these remarks, Deputy Secretary of State Lawrence Eagleburger publicly denounced Kearns and in February 1990 forced his resignation from the State Department. The Bush administration then transferred the F-16 technology to Japan.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Blowback, Second Edition: The Costs and Consequences of American Empire»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Blowback, Second Edition: The Costs and Consequences of American Empire» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Blowback, Second Edition: The Costs and Consequences of American Empire» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.