Chalmers Johnson - The Sorrows of Empire - Militarism, Secrecy, and the End of the Republic

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Chalmers Johnson - The Sorrows of Empire - Militarism, Secrecy, and the End of the Republic» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 2003, ISBN: 2003, Издательство: Macmillan, Жанр: Старинная литература, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:The Sorrows of Empire: Militarism, Secrecy, and the End of the Republic

- Автор:

- Издательство:Macmillan

- Жанр:

- Год:2003

- ISBN:9780805077971

- Рейтинг книги:4 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

The Sorrows of Empire: Militarism, Secrecy, and the End of the Republic: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «The Sorrows of Empire: Militarism, Secrecy, and the End of the Republic»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

The Sorrows of Empire: Militarism, Secrecy, and the End of the Republic — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «The Sorrows of Empire: Militarism, Secrecy, and the End of the Republic», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

The Americans believed that the Filipinos were too poor to evict them and that conservatives in the Philippine Senate would support them. However, after Mount Pinatubo destroyed Clark air base, the United States cut its offer of assistance to the Philippines from about $700 million to $203 million; and on September 16, 1991, irritated by America’s tight-fistedness and its refusal to undertake a cleanup of the pollution at Clark Field, the Philippine Senate, by a vote of twelve to eleven, rejected the proposed renewal of the 1947 bases agreement. 33Although the event was barely noted in the United States, all its military forces were completely withdrawn by November 24, 1992.

Since its expulsion, the United States has tried various stratagems to reintroduce its forces into the Philippines, always offering much-needed hard currency as an inducement. Early in 2002, we sent about a thousand Special Forces and supporting troops to help Filipinos fight the Abu Sayyaf, a Muslim “terrorist gang” on the southern island of Basilan with a record of kidnapping and extortion but not of political terrorism. 34The main U.S. goal in the Philippines has been to negotiate a “Mutual Logistics Support Agreement” that would allow us access to Philippine bases for refueling, reprovisioning, and repairing ships without a case-by-case debate. On August 3,2002, in Manila, Secretary of State Colin Powell said that “the United States is not interested in returning to the Philippines with bases or a permanent presence,” but it is unlikely that there was a single person in East Asia who believed him. 35On February 20,2003, the Pentagon announced that it was sending a new contingent of nearly 2,000 troops to the Philippines in an operation against “terrorists” that “has no fixed deadline.” 36

FROM WAR TO IMPERIALISM

As the American empire grows, we go to war significantly more frequently than we did before and during the Cold War. Wars, in turn, promote the growth of the military and are a great advertising medium for the power and effectiveness of our weapons—and the companies that make them, which can then more easily peddle them to others. According to the journalist William Greider, “The U.S. volume [of arms sales] represents 44 percent of the global market, more than double America’s market share in 1990 when the Soviet Union was the leading exporter of arms.” 37As the military-industrial complex gets ever fatter, with more overcapacity, it must be “fed” ever more often. The creation of new bases requires more new bases to protect the ones already established, producing ever-tighter cycles of militarism, wars, arms sales, and base expansions.

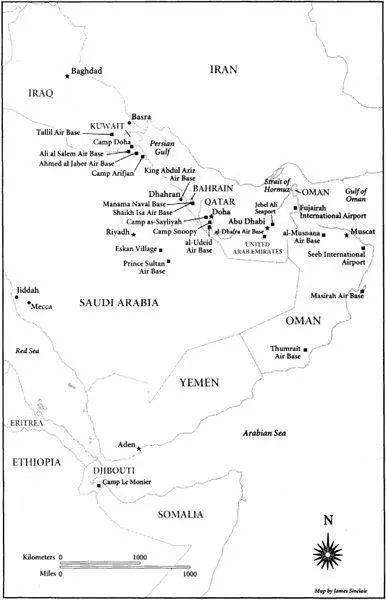

After the collapse of the Soviet Union, we began to wage at an accelerating rate wars whose publicly stated purposes were increasingly deceptive or unpersuasive. We were also ever more willing to go to war outside the framework of international law and in the face of worldwide popular opposition. These were de facto imperialist wars, defended by propaganda claims of humanitarian intervention, women’s liberation, the threat posed by unconventional weapons, or whatever current buzzword happened to occur to White House and Pentagon spokespersons. In each war we acquired major new military bases that in terms of location or scale were disproportionate to the military tasks required and that we retained and consolidated after the war. After the attacks of September 11,2001, we waged two wars, in Afghanistan and Iraq, and acquired fourteen new bases, in Eastern Europe, Iraq, the Persian Gulf, Pakistan, Afghanistan, Uzbekistan, and Kyrgyzstan. It was said that these wars were a response to the terrorist attacks and would lessen our vulnerability to terrorism in the future. But it seems more likely that the new bases and other American targets of vulnerability will be subject to continued or increased terrorist strikes.

Following our usual practice, we established our bases in weak states, most of which have undemocratic and repressive governments. Immediately after our victory in the second Iraq war, we began to scale back our deployments in Germany, Turkey, and Saudi Arabia, where we had become much more unpopular as a result of the war. Instead, we shifted our forces and garrisons to thinly populated, less demanding monarchies or autocracies/dictatorships, places like Qatar, Bahrain, Oman, the United Arab Emirates, and Uzbekistan. 38

A new picture of our empire has begun to emerge. We retain our centuries-old lock on Latin America and our close collaboration with the single-party government of Japan, although we are deeply disliked in Okinawa and South Korea, where the situation is increasingly volatile. Our lack of legitimacy in the war with Iraq has undercut our position in what Secretary of Defense Donald Rumsfeld disparagingly called “the old Europe,” so we are trying to compensate by finding allies and building bases in the much poorer, still struggling ex-Communist countries of Eastern Europe. In the oil-rich area of southern Eurasia we are building outposts in Kosovo, Iraq, Afghanistan, Pakistan, and Central Asia, in an attempt to bring the whole region under American hegemony. Iran alone, thus far, has been impervious to our efforts. We did not do any of these things to fight terrorism, liberate Iraq, trigger a domino effect for the democratization of the Middle East, or the other excuses proffered by our leaders. We did them, as I will show, because of oil, Israel, and domestic politics—and to fulfill our self-perceived destiny as a New Rome. The next chapter takes up American imperialism on the current battleground of global power, the Persian Gulf, a region where we have a long history.

PERSIAN GULF

8

IRAQ WARS

“From a marketing point of view,” said Andrew H. Card, Jr., the White House chief of staff on the rollout this week of the campaign for a war with Iraq, “you don’t introduce new products in August.”

New York Times, September 7,2002

After all, this is the guy [Saddam Hussein] who tried to kill my dad.

PRESIDENT GEORGE W. BUSH,

at Houston, September 26,2002

The Persian Gulf, a 600-mile-long extension of the Indian Ocean, separates the Arabian Peninsula on the west from Iran on the east. At the head of the gulf is Iraq, whose access to the waterway is largely blocked by Kuwait. Along the gulf’s western coast, from Kuwait to Oman, lie what in the nineteenth century were known as the “trucial states,” tribal fiefdoms that then lived by piracy and with whom Britain signed “truces” that turned them into British protectorates. The British were chiefly interested in protecting the shipping routes to their empire in India and so were ready to trade promises from local tribal leaders to suppress piracy for British guarantees to defend them from their neighbors. In this way, Britain became the supervisor of all relations among the trucial states as well as all their relations with the world outside the Persian Gulf.

Prior to World War II, the gulf area was thus a focus for British imperialism. Only in Saudi Arabia did events take a different turn when, in May 1933, the Standard Oil Company of California obtained the right to drill in that country’s fabulously oil-rich eastern provinces. In return for a payment of 35,000 British pounds, Standard of California (SoCal), known today as Chevron, obtained a sixty-year concession from King Ibn Saud to develop and export oil. Since British influence in the region was paramount, the Americans surely would not have gained a foothold had it not been for one of history’s most unusual figures, H. St. John Philby, Ibn Saud’s adviser and a specialist in Arabian matters. (He was also the father of Kim Philby, the British intelligence official who secretly went to work for the Soviet Union and became, after his defection to that country, the most notorious spy of the Cold War era.) Disturbed by the grossly imperialist practices of British oil companies in Iran, Philby persuaded King Ibn Saud to throw in his lot with the Americans. SoCal started oil production in Saudi Arabia in 1938. Shortly thereafter, the company and the monarchy formalized their partnership by creating a new entity, the Arabian-American Oil Company (Aramco), and brought in other partners—Texaco, Standard Oil of New Jersey (Exxon), and Socony-Vacuum (Mobil). Aramco has been described as “the largest and richest consortium in the history of commerce.” 1Its corporate headquarters are still located at Dhahran, Saudi Arabia.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «The Sorrows of Empire: Militarism, Secrecy, and the End of the Republic»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «The Sorrows of Empire: Militarism, Secrecy, and the End of the Republic» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «The Sorrows of Empire: Militarism, Secrecy, and the End of the Republic» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.