Chalmers Johnson - The Sorrows of Empire - Militarism, Secrecy, and the End of the Republic

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Chalmers Johnson - The Sorrows of Empire - Militarism, Secrecy, and the End of the Republic» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 2003, ISBN: 2003, Издательство: Macmillan, Жанр: Старинная литература, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:The Sorrows of Empire: Militarism, Secrecy, and the End of the Republic

- Автор:

- Издательство:Macmillan

- Жанр:

- Год:2003

- ISBN:9780805077971

- Рейтинг книги:4 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

The Sorrows of Empire: Militarism, Secrecy, and the End of the Republic: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «The Sorrows of Empire: Militarism, Secrecy, and the End of the Republic»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

The Sorrows of Empire: Militarism, Secrecy, and the End of the Republic — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «The Sorrows of Empire: Militarism, Secrecy, and the End of the Republic», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

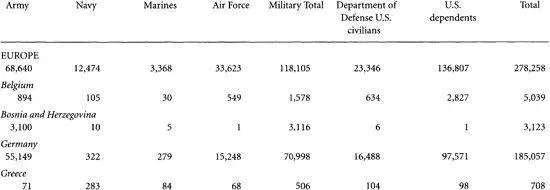

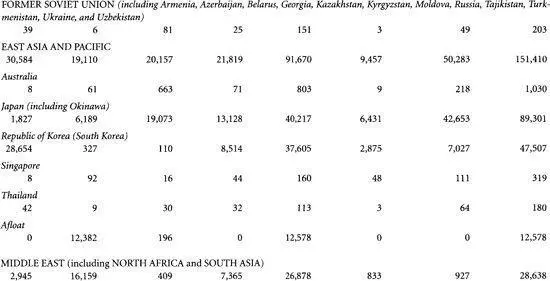

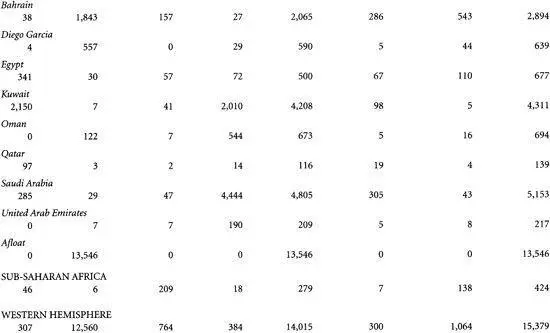

To begin to answer this question two official sources of data must be explored; both are of major importance although they differ in their standards of compilation. The Department of Defense’s Base Structure Report (BSR) details the physical property owned by the Pentagon, while the report on Worldwide Manpower Distribution by Geographical Area (Manpower Report) gives the numbers of military personnel at each base, broken down by army, navy, marines, and air force, plus civilians working for the Defense Department, locally hired civilians, and dependents of military personnel. 3

Both reports are supposed to be issued quarterly but actually appear intermittently. Neither report is inclusive, since many bases are cloaked in secrecy. For example, Charles Glass, the chief Middle East correspondent for ABC News from 1983 to 1993 and an authority on the Israeli-Palestinian conflict, writes, “Israel has provided the U.S. with sites in the Negev [desert] for military bases, now under construction, which will be far less vulnerable to Muslim fundamentalists than those in Saudi Arabia.” 4These are officially nonexistent sites. There have been press reports of aircraft from the carrier battle group USS Eisenhower operating from Nevatim Airfield in Israel, and a specialist on the military, William M. Arkin, adds, “The United States has ‘prepositioned’ vehicles, military equipment, even a 500-bed hospital, for U.S. Marines, Special Forces, and Air Force fighter and bomber aircraft at at least six sites in Israel, all part of what is antiseptically described as ‘U.S.-Israel strategic cooperation.’” 5These bases in Israel are known simply as Sites 51, 53, and 54. Their specific locations are classified and highly sensitive. There is no mention of American bases in Israel in any of the Department of Defense’s official compilations.

The Manpower Report is the more complete of the two in its worldwide coverage, but the BSR is critically important for two reasons. First, for every listed site it gives an estimated “plant replacement value” (PRV) in millions of dollars. Second, it gives details on some 725 foreign bases in thirty-eight countries, of which it defines 17 as “large installations” (having a PRV greater than $1.5 billion), 18 as “medium installations” (having a PRV between $800 million and $1.5 billion), and 690 as “small installations” (having a PRV of less than $800 million). According to the Department of Defense, “The PRV represents the reported cost of replacing the facility and its supporting infrastructure using today’s costs (labor and material) and standards (methods and codes).”

Although one must doubt the accuracy of any such estimates, particularly given the Pentagon’s record of incompetent accounting, they are nonetheless useful for making comparisons. Thus, according to Pentagon specialists, Ramstein Air Force Base near Kaiserslautern, Germany, the largest NATO air base in Europe, has a PRV of $2,458.8 million; whereas Kadena Air Force Base in Okinawa, the largest U.S. facility in East Asia, has a PRV nearly twice as large, at $4,758.5 million (and its adjoining Kadena Ammunition Storage Annex adds another $964.3 million). These are astronomical sums even though they probably underestimate real replacement values. In its detailed reports by country, the BSR lists foreign bases only if they are larger than ten acres and have a PRV greater than $10 million. Sites that do not meet these criteria are aggregated for each country as “other.” Only places with null or zero PRVs are not counted at all. These include small sites such as single, unmanned navigational aids or air force strategic missile emplacements. The 725 foreign bases, including the installations listed as “other,” have a total replacement value, according to the Pentagon, of $118 billion. This is a mind-boggling aggregation of foreign real estate and buildings possessed by the United States.

By contrast, the DoD’s Manpower Report does not list individual bases, only countries. It found that in September 2001, the United States was deploying a total of 254,788 military personnel in 153 countries. When civilians and dependents are included, the number doubles to 531,227. Since the Manpower Report does not say what the assignments are within a particular foreign country, one cannot distinguish between a country with American bases and a country with merely some embassy guards, a few special forces on a training mission, and perhaps some communications clerks. Therefore, it seems useful to consider only those countries with at least a hundred active-duty military personnel. These are likely to be assigned to bases. The total then, according to the DoD’s Manpower Report, is thirty-three, which comes close to the BSR’s list of significant bases in thirty-eight countries.

There are some major discrepancies between the BSR and the Manpower Report that are not easily explained. To give one important example, the BSR for September 2001 does not have any entries for Bosnia-Herzegovina or for Yugoslavia, Serbia, or Kosovo. The Manpower Report for the same month gives 3,100 for the number of army troops in Bosnia and 5, 675 for the number of army troops in the Serbian province of Kosovo. It is possible that Camp Eagle in Bosnia (built in 1995-96) and Camps Bondsteel and Monteith in Kosovo (both of which went up in 1999) were omitted intentionally in order to disguise their purpose—of protecting oil pipelines rather than contributing to international peacekeeping operations.

With such caveats, the table on pages 156-160 offers a snapshot of the American empire in terms of military personnel deployed overseas just before September 11, 2001. In the months following, the United States radically expanded its deployments everywhere but particularly in Afghanistan, elsewhere in Central Asia, and in the Persian Gulf.

Numerous bases are “secret” or else disguised in ways designed to keep them off the official books, but we know with certainty that they exist, where many of them are, and more or less what they do. They are either DoD-operated listening posts of the National Security Agency (NSA) and the National Reconnaissance Office (NRO), both among the most secretive of our intelligence organizations, or covert outposts of the military-petroleum complex. Officials never discuss either of these subjects with any degree of candor, but that does not alter the point that spying and oil are obsessive interests of theirs.

The United States operates so many overseas espionage bases that Michael Moran of NBC News once suggested, “Today, one could throw a dart at a map of the world and it would likely land within a few hundred miles of a quietly established U.S. intelligence-gathering operation....

FOREIGN DEPLOYMENTS OF U.S. MILITARY PERSONNEL AT THE TIME OF THE

TERRORIST ATTACKS ON THE WORLD TRADE CENTER AND THE PENTAGON

By Region and Country

September 2001

Only those countries with at least 100 active-duty U. S. military personnel are listed. Totals of the listed countries do not add up to the regional totals because the latter include all countries with any U.S. troops, regardless of the size of the contingent.

Интервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «The Sorrows of Empire: Militarism, Secrecy, and the End of the Republic»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «The Sorrows of Empire: Militarism, Secrecy, and the End of the Republic» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «The Sorrows of Empire: Militarism, Secrecy, and the End of the Republic» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.