Chalmers Johnson - The Sorrows of Empire - Militarism, Secrecy, and the End of the Republic

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Chalmers Johnson - The Sorrows of Empire - Militarism, Secrecy, and the End of the Republic» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 2003, ISBN: 2003, Издательство: Macmillan, Жанр: Старинная литература, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:The Sorrows of Empire: Militarism, Secrecy, and the End of the Republic

- Автор:

- Издательство:Macmillan

- Жанр:

- Год:2003

- ISBN:9780805077971

- Рейтинг книги:4 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

The Sorrows of Empire: Militarism, Secrecy, and the End of the Republic: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «The Sorrows of Empire: Militarism, Secrecy, and the End of the Republic»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

The Sorrows of Empire: Militarism, Secrecy, and the End of the Republic — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «The Sorrows of Empire: Militarism, Secrecy, and the End of the Republic», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

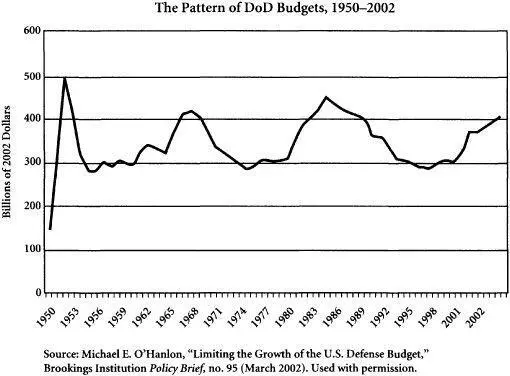

The first and most significant peak in weapons purchases occurred during the Korean War (1950-53), even though only a fraction of it went for armaments to fight that war. Most of the money went into nuclear weapons development and the stocking of the massive Cold War garrisons then being built in Britain, Germany, Italy, Japan, and South Korea. Defense spending rose from about $150 billion in 1950, measured in 2002 purchasing power, to just under $500 billion in 1953. The second buildup financed the Vietnam War. Defense spending in 1968 was over $400 billion in 2002 dollars. The third boom was Ronald Reagan’s splurge, including huge investments in weapons systems like the B-2 stealth bomber and in high-tech research and development for his strategic defense initiative, funds that were largely hidden in the Pentagon’s “black budget.” Spending hit around $450 billion in 1989. The second Bush administration launched the latest binge in new weaponry, fueled in part by public reaction to the 9/11 attacks. On March 14, 2002, the House of Representatives passed a military budget of $393.8 billion, the largest increase in defense outlays in almost twenty years. 27

But no less significant is what happened to the military budget between the peaks. At no moment from 1955 to 2002 did defense spending decline to pre-Cold War, much less pre-World War II, levels. Instead, the years from 1955 to 1965, 1974 to 1980, and 1995 to 2000 established the Cold War norm or baseline of military spending in the age of militarism. Real defense spending during those years averaged $281 billion per year in 2002 dollars. Defense spending even in the Clinton years, after the collapse of the Soviet Union, averaged $278 billion, almost exactly the Cold War norm. The frequent Republican charge that Clinton cut military spending is untrue. In the wake of the Reagan defense buildup, which had so ruined public finances that the United States became the world’s largest debtor nation, he simply allowed military spending to return to what had become its normal level.

From the Korean War to the first years of the twenty-first century, the institutionalization of these huge defense expenditures fundamentally altered the political economy of the United States. Defense spending at staggering levels became a normal feature of “civilian” life and all members of Congress, regardless of their political orientations, tried to attract defense contracts to their districts. Regions such as Southern California became dependent on defense expenditures, and recessions involving layoffs during the “normal” years of defense spending have been a standard feature of California’s economy. In September 2002 it was estimated that the Pentagon funneled nearly a quarter of its research and development funds to companies in California, which employed by far the largest number of defense workers in any state. Moreover, this figure is undoubtedly low because many Southern California firms, like Northrop Grumman in Century City, TRW in Redondo Beach, Lockheed Martin in Palmdale, and Raytheon in El Segundo, are engaged in secret military programs whose budgets are also secret. 28

Americans are by now used to hearing their political leaders say or do anything to promote local military spending. For example, both of Washington State’s Democratic senators, Patty Murray and Maria Cantwell, as well as a Republican senator from Alaska, Ted Stevens, voted to include in the fiscal year 2003 defense budget some $30 billion to be spent over a decade to lease Boeing 767 aircraft and modify them to serve as aerial tankers for refueling combat aircraft in flight, a project not even listed by the air force in its top sixty priorities or among its procurement plans for the next six years. The bill also provided for the air force’s paying to refit the planes for civilian use and deliver them back to Boeing after the leases were up. “It is in our national interest... to keep our only commercial aircraft manufacturer healthy in tough times,” Murray commented. 29Boeing, of course, builds the planes at factories in Washington State. In 2000, Stevens, an influential member of the Senate Appropriations Committee and its Defense Appropriations Subcommittee, received a $10,000 donation to his personal reelection campaign and $1,000 for his political action committee from Boeing; in 2001, it gave him an additional $3,000. Dennis Hastert, the Speaker of the House of Representatives, so liked the provisions in the bill that he tacked on funds for the leasing of four new Boeing 737 airliners for congressional junkets. Such obvious indifference to how taxpayers’ monies are spent, bordering on corruption, no longer attracts notice. It has become a standard feature of politics.

The military-industrial complex has also become a rich source of places to “retire” for high-ranking military officers, just as many executives of defense contractors receive appointments as high-ranking officials in the Pentagon. This “circulation of elites” tends to undercut attempts at congressional oversight of either the Defense Department or defense contractors. The result is an almost total loss of accountability for public money spent on military projects of any sort. As Insight magazine journalist Kelly O’Meara has noted, in May 2001 the deputy inspector general at the Pentagon “admitted that $4.4 trillion in adjustments to the Pentagon’s books had to be cooked to compile... required financial statements and that $1.1 trillion ... was simply gone and no one can be sure of when, where or to whom the money went.” 30This amount is larger than the $855 billion in income taxes paid by Americans in fiscal 1999. The fact that no one seems to care is also evidence of militarism.

The onset of militarism is commonly marked by three broad indicators. The first is the emergence of a professional military class and the subsequent glorification of its ideals. Professionalism became an issue during the Korean War (1950-53). The goal of professionalism is to produce soldiers who will fight solely and simply because they have been ordered to do so and not because they necessarily identify with, or have any interest in, the political goals of a war. In World War II, the United States fought against two enemies, Nazi Germany and militarist Japan, that, with the aid of government propaganda, could be portrayed as genuinely evil. 31

The United States did its best to depict the North Koreans, and particularly the Communist Chinese, who entered the war in late 1950, as “yellow hordes” and “blue ants,” but as James Michener’s novel The Bridges at Toko-Ri (1953) so well described, the public was much less emotionally involved than it had been during World War II. With public support slackening, the military high command turned to inculcating martial values into the troops, making that the most vital goal of all military instruction, superseding even training in the use of weapons. These values were to include loyalty, esprit de corps, tradition, male bonding, discipline, and action—generally speaking, a John Wayne view of the world. And inasmuch as conscripts constituted most of the still citizen army in those years, there was much work to do. Combat veterans of World War II tended to denigrate Wayne for his Hollywood-style machismo displayed in films like Fighting Seabees (1944). William Manchester, the biographer of General Douglas MacArthur and himself a veteran of the war in the Pacific, recalled how, shortly after the Battle of Okinawa, wounded soldiers and marines booed Wayne, who did not serve in the military, off a stage at the Aiea Heights Naval Hospital in Hawaii when he walked out in a Texas hat, bandanna, checkered shirt, two pistols, chaps, boots, and spurs. 32

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «The Sorrows of Empire: Militarism, Secrecy, and the End of the Republic»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «The Sorrows of Empire: Militarism, Secrecy, and the End of the Republic» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «The Sorrows of Empire: Militarism, Secrecy, and the End of the Republic» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.