It’s your job to win .

San Francisco

August 14–17, 1949

The day before Charles Cousens was scheduled to testify, Iva Toguri ran into his arms and cried tears of joy.

Part of the reason Iva was so happy to see Cousens was that she knew he could rebut all the lies told by Mitsushio and Oki. The other part was that she had simply missed him. His confidence and determination, his talent for writing and comedy, and his interest in coaching and leading Iva in a secret mission against the Japanese had been important to her during the war.

Several days later, on Cousens’s third day of testimony in Iva’s defense, she had something else to smile about. DeWolfe had asked him, “Did any other Japanese bring you food besides the defendant?”

Cousens did not miss a beat. “The defendant was not Japanese,” he replied. “She was an American.”

San Francisco

September 7–15, 1949

On the forty-sixth day of what had become the most expensive prosecution in American history, Iva Toguri raised her right hand and, with an American flag standing behind her, took the witness stand and swore to tell the truth.

As she looked out at her husband, father, and siblings in the row behind the defense table, she knew they were worried about the decision she’d made to testify. But she didn’t share their fears. Iva understood what was at stake in this trial, but she was sure that if she took the stand and was honest, then the truth would prevail. This is America , she told herself. The system works .

Over four days of direct examination Toguri described her entire life, from her childhood in California through her broadcasts at Radio Tokyo and her interview with Clark Lee and Harry Brundidge. At the end, her attorney, Wayne Collins, finally asked her, “Did you do anything whatsoever with intent to undermine or lower American or Allied military morale?”

“Never,” she replied.

“Did you do anything with intent to create nostalgia in the mind of Americans or Allied armed forces?”

“Never.”

“Did you do any act whatsoever with the intention of betraying the United States?”

“Never.”

“Did you at any time whatsoever commit treason against the United States?”

There it was, the word that had haunted her since Clark Lee’s “Traitor’s Pay” article; the word that had been flung around recklessly by Walter Winchell and Harry Brundidge for the past two years: traitor .

Iva’s anger and outrage were boiling inside her, but she kept her emotions in check, offering only the slightest glimpse of them by the forcefulness with which she replied to Collins’s last question.

“Never.”

San Francisco

September 29, 1949

Rising to her feet as the judge and jurors entered the courtroom, Iva stared down at her tan plaid skirt, the same unflattering, out-of-style one she’d ironed in her jail cell every night and worn to her trial every day.

“Has the jury arrived at a verdict?” asked Michael Roche, the seventy-two-year-old federal judge who had issued jury instructions that were extremely detrimental to the defense. Roche had told the jurors that they were not to consider Iva’s giving of food and medicine when judging her intentions. They were also forbidden to consider her refusal, even in the face of constant intimidation from the secret police, to renounce her American citizenship.

It was 6:04 P.M. on the fourth day of jury deliberations and it seemed that another full day and night was about to pass with no resolution in sight. No one in the courtroom expected that a verdict had been reached.

The judge didn’t expect it. He had recently suggested to the jurors that they take a break for dinner.

The spectators didn’t expect it. If a verdict had been likely at this hour, there would have been more than forty people in the largely empty courtroom.

The press didn’t expect it. Only ten journalists were milling around the courtroom at this late hour.

And Iva certainly didn’t expect it—though by this point she had pretty much lost all faith in her ability to predict events. She once thought that after the jurors heard the defense witnesses and her own testimony, an acquittal would come quickly. But her confidence had been shaken by the four days of jury deliberations. “If they go more than a day,” her attorney had told her, “it’s not a good sign.”

In response to Judge Roche’s question of whether the jury had reached a verdict, John Mann, the pleasant bookkeeper acting as jury foreman, replied, “We have, Your Honor.”

The court clerk took the verdict form from Mann. He passed it to the judge, who read it in silence, before returning it to the clerk, who broke the silence with a single word.

“Guilty.”

EPILOGUE

Chicago, Illinois

Forty years later: January 13, 1989

The Toguri Mercantile shop on North Clark Street was closed for the evening. Iva sat at her small desk in the back room, reviewing the day’s receipts and filling out quarterly tax forms. For more than three decades, she had worked at the store her father founded. Now, at seventy-three years old, she was the store’s owner, manager, accountant, and primary salesperson.

Most of the store’s customers had no idea that the petite shopkeeper had once been convicted of treason. Or that she had lost her American citizenship upon her conviction, had served more than six years in federal prison, and had then barely escaped deportation when her enemies tried to expel her from the country as an “undesirable alien” after her release. They certainly did not know that the government had destroyed her marriage by barring her husband from entering the country.

These customers also did not know that John Mann, the jury foreman, had quickly come to regret the verdict he and two other holdouts had begrudgingly been persuaded by the other nine jurors to approve. They could not have known that Thomas DeWolfe, who had been instrumental in taking six years of Iva’s life, had taken his own just three years earlier.

And they had no idea that the owner of the Toguri Mercantile shop had received a full, unconditional pardon from the president of the United States in 1977. In doing so, Gerald Ford had finally returned to Iva Toguri the one thing she had so defiantly clung to for so many years: her American citizenship.

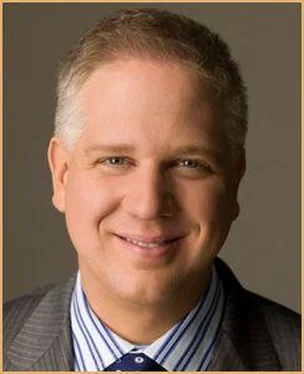

As Iva closed the account books, marking the end of another fourteen-hour workday, she glanced at the photograph on her desk of a distinguished-looking man with a confident, charming smile.

And after all these years, she was still comforted by Charles Cousens.

Seventeen years later: January 16, 2006

Iva had tried to keep her emotions bottled up inside her during the trial. But now, at a solemn ceremony in downtown Chicago, the eighty-nine-year-old saw no reason to hold them back any longer.

“Throughout an ordeal that has lasted decades,” declared a broad-shouldered, aging World War II veteran, who was more than a head taller than the ceremony’s guest of honor, “Iva Toguri has endured her fate with dignity, courage, and a deep faith in God and in the essential fairness of the American system.”

As Iva wiped tears from her face, the veteran continued: “For her indomitable spirit, her love of country, and the example of courage she has given her fellow Americans, the World War II Veterans Committee proudly bestows the 2005 Edward J. Herlihy Citizenship Award on Iva Toguri.”

During the same time that Iva was trying to cheer up American soldiers and sailors in the Pacific, Edward Herlihy had become so famous announcing newsreels that he had been called “The Voice of World War II.” After being the object of a media witch hunt, it was one of life’s great ironies that Iva was now about to accept an award named after an American journalist.

Читать дальше