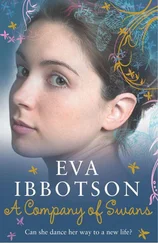

A Swans - Eva Ibbotson

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «A Swans - Eva Ibbotson» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 0101, Жанр: Старинная литература, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Eva Ibbotson

- Автор:

- Жанр:

- Год:0101

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:3 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Eva Ibbotson: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Eva Ibbotson»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

Eva Ibbotson — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Eva Ibbotson», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

“Oh… Thank you !” She paused. “You see, my father… didn’t exactly give me permission.”

“Yes,” said Dubrov heavily, “I gathered this. Perhaps you should tell me…”

Later, meeting Grisha in the corridor, he said, “Well, how is she, my little protegee?”

Grisha shrugged. “It is a pity. But there; it is only their horses that the British train properly. And now it’s too late… I think?” He pondered and added, “ Elle est’sérieuse .”

Serious. Not lacking in humor, not pompous or self-important, but serious—giving the job the full weight of her being.

Dubrov nodded and passed on.

The principal dancers, unlike the rest of the Company who were in lodgings or hostels, were accommodated in the Queen’s Hotel in Bloomsbury until their date of departure: a draughty place with dingy lace curtains and terrible food, but handy for the theater and where the proprietors were friendly and accustomed to the vagaries of their foreign guests.

In this hotel, as in all the others where the dancers had stayed, Dubrov’s room adjoined that of the ballerina, Galina Simonova. Since Simonova’s views on “passion as an aid to the dance” were well-known, it might be concluded that Dubrov enjoyed what were technically known as conjugal rights, and this was so. Dubrov’s rights, however, were granted to him on such uncertain terms—were so dependent on the state of Simonova’s back, her Achilles tendon and her reviews—that he had learned to temper the wind to the shorn lamb in a way which was not unremarkable in a man who had once written a ninety-stanza poem in the style of Pushkin entitled Eros Proclaimed .

The evening of Harriet’s arrival at the theater, he found Simonova lying on the sofa—an ominous sign-staring with black and tormented eyes at her left knee.

“It’s going again, Sashka; I can feel it! Dimitri has given me a massage, but it’s no use—it’s going. We must cancel the tour!”

He came over to sit beside her and felt her knee, considerably more familiar to him than his own. “Let me see.”

Her knee, her cervical vertebrae, the bursa on her Achilles tendon… he knew them like men know their children and now, as his stubby fingers moved gently over the joint, he wondered for the thousandth time why fate had linked him indissolubly with this temperamental, autocratic woman.

Sitting with balletomane friends in his box in the bel étage at the Maryinsky in St. Petersburg, he had picked her out of the corps . “That one,” he had said, pointing at the row of water sprites in Ondine , and he was right. She became a coryphée , a soloist…

It was not difficult in those days to enjoy her favors; he was young and rich and could present her own image to her in the way that women have always found irresistible. “If you give me half an hour to explain away my face, I could seduce the Queen of France,” said Voltaire—and Dubrov, though uninterested in royalty, could have said the same.

He bought her an apartment on the Fontanka Canal and she was moderately faithful for she was obsessed by dancing—by her career. Outside revolutions rumbled, Grand Dukes were assassinated and picked off the cobbled streets in splinters, but to Simonova it mattered only that she ended badly after her pique turns in Paquita or started her solo a bar too soon. And because it was this that he loved in her—this crazy obsession with the art that he too adored—he put up with it all, became manager, masseur, choreographer, nurse…

She rose steadily in the ranks of the Maryinsky. They gave her the Lilac Fairy, then Swanhilda in Coppélia and at last Giselle . After her first night in that immortal ballet, he watched one of the great cliches of the theater brought to life—the students unharnessing the horses from her carriage in order to pull her through the streets—but later she had cried in his arms because she had not got her fall right in the Mad Scene: it was clumsy, she said, and the timing was wrong.

A year later she threw it all away in a stupid, unnecessary row with the management, refusing to wear the costume they had designed for her in Aurora’s Wedding and appearing instead in a costume she preferred. She was fined and told to change it. She refused. No one believed it would come to anything for the hierarchical, bureaucratic theater was full of such scenes, but Simonova with childish obstinacy forced the director to a confrontation and when she was overruled, she resigned. Resigned from the theater she adored, from the great tradition which had nourished her, and went to Europe. And Dubrov, too, exiled himself from his homeland, sold his interests in Russia and created a company in which she could dance.

Since then they had toured Paris and Rome, Berlin and Stockholm, and it was understood between them that she hated Russia, that she would not return even if they asked her to do so on bended knees. For eight years now they had been exiles and it was hard—finding theaters, getting together a corps , luring soloists from other companies. Of late, too, there had been competition from other and younger dancers—from Pavlova, who had also come to Europe; from the divine Karsavina, Diaghilev’s darling, who with Nijinsky had taken the West by storm. Simonova owned to thirty-six, but she was almost forty and looked it: a stark woman with hooded eyes and deep lines etched between her autocratically arched brows.

“We should never have attempted this tour,” she said now. “It’s madness.”

Fear again. It was fear, of course, that ailed her knee… fear of failure, of old age… of the new Polish dancer, Masha Repin, who had joined them three days earlier and was covering her Giselle…

“You have told them it is my farewell performance?” she demanded. “Positively my last one? You have put it on the posters?”

Dubrov sighed and abandoned her knee. This was the latest fantasy—that each of her performances was the last, that she would not have to submit her aging body to the endless torture of trying to achieve perfection anymore. He knew what was coming next and now, as she moved his hand firmly to her fifth vertebra, it came.

“Soon we shall give it all up, won’t we, Sashka, and go and live in Cremorra? Soon…”

“Yes, dousha , yes.”

“It will be so peaceful,” she murmured, arching her back to give him better access. “We shall listen to the birds and have a goat and grow the best vegetables in Trentino. Won’t it be wonderful?”

“Wonderful,” agreed Dubrov dully.

Three years earlier, returning from a tour of the northern cities of Italy—in one of which a critic had dared to compare Simonova unfavorably with the great Legnani—the train that had been carrying them toward the Alps had come to a sudden stop. The day was exquisite; the air, as they lowered the window, like wine. Gentle-eyed cows with bells grazed in flower-filled fields, geraniums and petunias tumbled from the window-boxes of the little houses, a blue lake shimmered in the valley.

All of which would not have mattered except that across a meadow, beside a sparkling stream, one of the toy houses proclaimed itself “For Sale.”

To this oldest of fantasies, that of finding from a passing train the house of one’s dreams, Simonova instantly responded. She seized two hat-boxes and her dressing-case, issued a torrent of instructions to her dresser and pulled Dubrov down onto the platform.

Two days later the little house in Cremorra—complete with vegetable garden, grazing for a substantial number of goats, three fretwork balconies and a chicken-house—was his.

Fortunately, in Vienna the critics were kind and it was not too often that Simonova remembered the little wooden house which a kind peasant lady was looking after. They had spent a week there the year after he bought it and Dubrov had been rather ill, for there was a glut of apricots in their delightful orchard and Simonova had made a great deal of jam which did not set. Of late, however, Cremorra was getting closer and Dubrov, to whom the idea of living permanently in the country among inimical animals and loosening fruit was horrifying, now searched his mind for a diversion.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Eva Ibbotson»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Eva Ibbotson» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Eva Ibbotson» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.