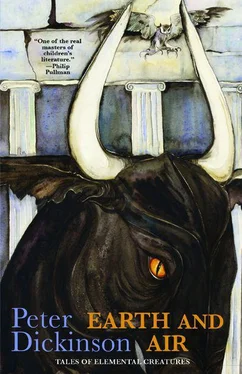

Peter Dickinson - Earth and Air

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Peter Dickinson - Earth and Air» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 2012, ISBN: 2012, Издательство: Big Mouth House, Жанр: Старинная литература, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Earth and Air

- Автор:

- Издательство:Big Mouth House

- Жанр:

- Год:2012

- ISBN:9781618730398

- Рейтинг книги:5 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Earth and Air: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Earth and Air»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

Earth and Air — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Earth and Air», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

Yanni turned back to the temple to see what it was, but there was nothing, only the blackness of the new-moon night where the threads all came together directly above the Bloodstone, on which the new god was now standing. He seemed even taller than before. His head topped the line of pillars. He too gazed skyward, raising his arms to the sky for a fresh outpouring of his strength.

Out of that sky, sudden as lightning, fell a shape, a blackness, a piece of the night itself. With the neck-breaking thud of a hunting owl as it strikes its prey it hit the god full in the face. Immense wings, wide as the temple itself, beat violently. The god, caught utterly by surprise, tumbled from the Bloodstone, tripped on the prone body of a dancer, staggered and lay flat, while the hooked beak plunged down again and again at the head gripped between the savage talons.

And the god withdrew from the shape he had inhabited and slipped away.

The red light dimmed and died. By its last glimmer Yanni saw the owl rise on silent wings and vanish into the darkness of night.

Suddenly he was aware of his nakedness, and of the women with the lanterns beginning to move down the slope behind him. He scuttled up to the temple, found his clothes, hurried into the darkness beyond the firelight and started to put them on.

The night was full of voices, triumphant, questioning, angry. Somebody was calling his name.

“Yanni! Yanni! Where are you?”

“Euphanie! Here! Euphanie!”

Half-dressed he stumbled towards the light of the fire. She came rushing towards him out of the dark and flung her arms round him.

“You’re all right! Oh, you’re all right! You did it!”

“I . . . I think so . . . But you . . . How . . .?”

“I couldn’t go to bed. She came to me in a waking dream. She said I must come. The same with the other women. She told us what to do. They’re catching the men now. I don’t know what they’ll do to them . . . Oh, Yanni! That . . . that thing! ”

Still appalled by the vision, she was gazing beyond Yanni into the House of the Wise One to where the dark god had stood. He turned. Nobody had yet dared to pass between the pillars, and the temple was empty. The fire was dying, but by its faint light he could see something lying between beside the Bloodstone where the god had fallen. Surely . . . No, it was too small, a human shape. Pulling on the rest of his clothes he took her lantern and went to look.

The face was a tangled mess of beard and blood. Both eye sockets were bloody pits. The pale, naked torso was streaked with dark runnels where the molten flesh of the god’s visage had dribbled down it. On the middle finger of the left hand there was a wide silver ring.

Yes, of course, he thought. In his heart he had known it all along. He went back to Euphanie.

“Papa Archangelos,” he told her. “I suppose he chose me because he thought I’d be an easy victim. Like Nana. Let’s go home.”

“Where’s Scops?”

“I don’t know.”

Lamplight gleamed through the kitchen shutters. The census-taker’s sister was waiting for them, with Scops on her wrist. There was a meal on the table, cheese, olives, oil and bread, water and wine, and places set for three.

“All is well,” she told them. “We could not have done it without you, nor you without us, nor either without Scops. The dark god will return, but not to this island yet, and meanwhile my blessing is upon it, and upon you two, and yours, for as long as you live.

“We old gods have used our last power, and now we are going, and will not return. The glamour I gave you, Yanni, will go with me. You are better off without it. These things belong to the gods, and destroy mortals who use them too long. Papa Archangelos had been a man, remember, and might have been a great one. Tell no one what has happened apart from your own children.”

“I wouldn’t anyway. Papa Archangelos may be dead, but that won’t stop the church stoning people for witchcraft. And the women who came, they’ll all be too scared to do any more than whisper among themselves.”

“Good. But remember to tell your children, yours and your sister’s. And their children after.”

“All right. What about Scops?” he asked.

“Oh, she will stay, and mate and rear young, and die like any other owl. But my blessing is on her too. Go to Yanni, little one. No wait.”

She broke bread from the loaf, dipped it in water, and used it as a sponge to wipe a few traces of dark blood from Scops’s face-feathers, then raised her arm to kiss the bird farewell. Scops nibbled the tip of her nose affectionately and flipped herself across to Yanni’s shoulder.

Yanni turned his head to greet her. When he looked back the goddess was gone.

EPILOGUE

One late summer afternoon two old people, brother and sister, sat in front of the house where both of them had been born almost a hundred years before. Below them, terrace after terrace, stretched their vines and olive trees, and beyond that a placid sea, with two islands on the horizon, cloudy masses against the bright streaks of sunset. Around them sat, or strolled, or scampered, the enormous gathering of their joint family, sons and daughters and grandchildren, all with their husbands or wives, great-grandchildren, two by now also married, and one great-great-grandchild, the first of all the brood to descend from both brother and sister, for her parents were second cousins. That was why everyone had come to celebrate her naming day. Though several of the husbands and wives had died, none of the direct descendants was missing, for they were a long-lived family and those who had married had done so for love and stayed loving. Many had come from the island, more from other islands nearby, or the mainland, some from far-off cities. There were farmers and fishermen there of course, but also merchants and craftspeople—one of the grand-daughters was a famous weaver, whose work hung in palaces and cathedrals—a scholar or two, a judge and two other lawyers, priests, monks and a nun with special dispensations to leave their monasteries—all there for this day.

Now an owl floated out of nowhere, settled on the old man’s shoulder and sat blinking at the red sun. The light darkened. Voices became hushed and fell silent, as if a long-hidden knowledge had woken suddenly in the blood they all shared.

“ Prrp, prrp, ” said the owl, and the evening air filled with owls. Owls are territorial birds, and it is rare to see more than two together once they have left the nest for good, but for this evening they appeared to have forgotten their boundaries and eddied in silent swirls above the human gathering.

Now some came lower, and the children raised their arms as the owls swooped and turned among them, and ran in interweaving circles, as if birds and people were taking part in some game or dance whose rules none of them knew but all of them understood. The watching adults clapped out a rhythm and the owls called to and fro.

In the middle of the calling and clapping the owl on the old man’s shoulder, the fourteenth Scops of that name and line, called again, “ Prrp, prrp, ” so softly that one would have thought only the two old people could have heard, but one owl broke from the dance and flew towards them. The old man stretched out a shaky arm and the owl settled onto it, a bit clumsily, as she was one of this year’s hatch and had not been flying more than a week or two. The woman reached out and the young owl leaned luxuriatingly against her touch as her fingers gentled among her neck feathers.

“Well,” said the old woman. “They’re all here. Which of them are you going to choose?”

The owl flipped itself up onto the old man’s shoulder, scrabbled for a hold and then perched beside the older one, studying the crowd below. It slid away and was lost among the swirling owls. But in less than a minute the dance stilled. The children stood where they were and the birds swung away to perch among the olives, all but one, which hovered for a moment in a blur of soft wings and settled on the shoulder of a nine-year-old girl.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Earth and Air»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Earth and Air» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Earth and Air» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.