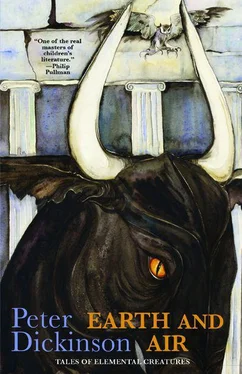

Peter Dickinson - Earth and Air

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Peter Dickinson - Earth and Air» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 2012, ISBN: 2012, Издательство: Big Mouth House, Жанр: Старинная литература, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Earth and Air

- Автор:

- Издательство:Big Mouth House

- Жанр:

- Год:2012

- ISBN:9781618730398

- Рейтинг книги:5 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Earth and Air: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Earth and Air»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

Earth and Air — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Earth and Air», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

Scops woke at dusk, shrilly demanding to be fed, and Yanni would cram chewed mouse into the gaping mouth until she turned her head away and with a quick, gulping shudder excreted neatly over the side of her nest into the bottom of the jar. Then he would move her, nest and all, into a smaller bowl which he carried into the house and set on the table beside him so that he could feed her chewings of what he was eating, his ears pricked for the rattle of the chain that fastened the gate at the top of the steep path. Every few evenings he practised the drill of whisking her into the old bread oven and piling against it the logs he kept ready beside it. In the end he could do this to a count of eight, whereas he always fastened the gate in such a way that even in daylight it took a count of fourteen to unwrap the chain and reach the door. The need never arose, but it was a way of reminding himself to be careful.

Scops spent the night in the oven with the door a crack ajar, and at first light was already calling for food. Never in his life had Yanni regularly risen so early. He fed her before he breakfasted and took her out to the barn when he and Euphanie set off for their day’s work.

In two weeks she had doubled her size, and the same two weeks later. By then she had learnt to scrabble out of her bowl and explore round the table while they ate. Already she was moulting her baby down and the quills of her first true feathers were poking through what was left. Her head could swivel through a complete circle in either direction, so that if she happened to be looking Yanni’s way when she stretched and flapped her skimpy wings, her large-eyed owl stare gave her an expression of utter bafflement that they hadn’t done their job and carried her into the air.

Mobility made the problem of her droppings much more difficult. Birds, Euphanie said, were untrainable, so Yanni watched her every instant she was loose, at first with a damp cloth ready to hand. Soon though he learnt the almost imperceptible signal and if he was quick enough could catch the splatter directly onto the cloth. He applied the same vigilance to all her leavings, the moulted feathers, the little pellets of mouse bones she would from time to time cough up, and so on.

“You are getting even more fussy than me,” said Euphanie, teasing.

“Going to church helps,” said Yanni, dead serious. “Seeing him again, week after week. He’s not going to give up.”

By now it was high summer. The spring rains had been kindly, almost healing the ravages of last year’s drought. Between the dew-sweet dawns and the dusty cool of the evenings the island seemed to drowse its days away, purring gently as it slept. But it was not at peace. Papa Archangelos was a disturbing priest. People didn’t know what to expect when they saw the tall black figure pacing towards them along one of the network of tracks that crisscrossed the island. True to his promise he knew everyone in his flock by now, not only their names but their hopes and troubles, and their place in the complex kinships that, rather like those connecting tracks, linked the community together. On meeting he would bless you, and ask a few friendly seeming questions, bringing himself up to date with your affairs since you had last met him, but as you parted you felt he had seen into your inmost heart. Few of the islanders went to formal confession, and those only once a year, travelling to a priest on another island to do so for greater secrecy. Papa Archangelos put no pressure on his flock to come to him. There was no need. He knew.

He was a wonderful preacher, using images of fishing and farming and housekeeping, things the islanders understood. He spoke of the Lord Jesus as if he had met him and talked with him face-to-face, walking the same earth they did and breathing the same air. But every now and then he spoke of a different Christ, the huge-eyed frowning judge whom they could just make out up in the smoky mosaics in the dome of the church, and to whom they would answer on the day of judgment for every ill deed, every sinful thought, every wicked dream in all their lives. At these times he seemed to grow taller as he spoke, and darker, the soft voice whispering though the breathless stillness until the air in the church felt midwinter cold. More than once someone listening had screamed, or shouted in terror, and rushed out into the sunlight. Yanni needed no other reminders to be careful to keep the existence of Scops a secret.

In fact the house where he lived with Euphanie was the last on a track that led nowhere useful, and Papa Archangelos didn’t return there till the grapes were ripe on the vines. By then Scops was flying, and no longer roosted in the jar on the shelf, but on a beam up in the barn, as a wild owl might well do. She slept most of the day, but when he returned with Euphanie from the fields in the evening she would wake at the rattle of the gate and as they reached the door of the house would drift down with her uncanny silent flight, noiseless as a falling leaf, and settle on his shoulder and nibble his ear while he teased the feathers at the back of her neck. Then she would go off and hunt, but not very seriously, knowing she would find food at the house when she returned.

One such evening Papa Archangelos was waiting for them at the gate.

Yanni’s heart lost a beat, and another. There was vomit in his throat. But his legs walked on, helpless.

Euphanie knew what to do.

“Take the corn into the barn,” she whispered. “Leave it there. Say hello to Scops, then come. He’ll be gone before she’s finished hunting.”

Papa Archangelos raised his hand in blessing as they approached and waited for Euphanie to open the gate. She handed her basket to Yanni, and led the way through. Yanni came last, turning aside with both baskets, and on round the corner of the house to the barn. As he reached for the latch Scops did her silent swoop to his shoulder and nibbled his ear. His panic eased.

“Stay clear till he’s gone,” he whispered. “We don’t want him to see you.”

She didn’t of course understand the words, but she seemed to sense his tension and slipped away to become part of the gathering dusk. Inside the house he found Papa Archangelos sitting at the table with a jar of wine, bread, and a dish of olives beside him, and Euphanie still standing, opposite. It wasn’t the custom of the island for a woman to sit if a man, not a member of the family, was in the room. Papa Archangelos waved Yanni to the other chair, as if this had been his house.

“I cannot stay long,” he said. “I have two things to tell you. The first is for you alone, and is sad news. You remember I told you I would try to find whether your father still lived. I have not been wholly successful, but a priest I know in Alexandria tells me there is very good reason to believe that your father died of the plague in that city four years ago. He was working in the docks there when the plague struck and was not among those recorded as having left, and was not seen again. I am sorry, my children. He may not have been a good father to you, but your father he was, nonetheless. Let us pray for his soul.”

He rose, so Yanni did the same and stood with his head bowed while the priest whispered three short prayers. In the silence that followed he could hear the throb of his own heart. Something was going to happen. Something . . .

“Thank you, Father,” said Euphanie, and Yanni managed to mumble his own thanks.

“The second thing,” said Papa Archangelos more briskly, “I am telling everyone on the island. Our blessed Emperor has ordered a census of all his peoples, and soon the census takers will be coming to this island. There is nothing to fear from them, provided you tell them the truth. The penalties for lying are very harsh. You understand.”

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Earth and Air»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Earth and Air» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Earth and Air» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.