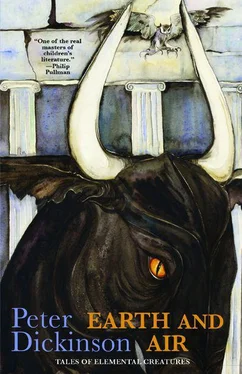

Peter Dickinson - Earth and Air

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Peter Dickinson - Earth and Air» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 2012, ISBN: 2012, Издательство: Big Mouth House, Жанр: Старинная литература, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Earth and Air

- Автор:

- Издательство:Big Mouth House

- Жанр:

- Год:2012

- ISBN:9781618730398

- Рейтинг книги:5 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Earth and Air: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Earth and Air»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

Earth and Air — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Earth and Air», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

All the bits of carcass he had strewn around the place were now picked bare. Apart from what was in Varro’s cache nothing remained except bones, a feathered skull with an amazing beak, and the hide slung between the temple pillars. As the sun went down on his ninth day he took that down, folded it and piled masonry over it. One day, perhaps, he would be able to come back for it. He might even make a saddle out of it, if the leather wasn’t ruined by then.

Five days later, still feeling reasonably strong, Varro reached a nomadic encampment at the far edge of the desert. The herders spoke no language that he knew, and would take no payment for their hospitality, but when he spoke of Dassun in a questioning tone they set him on his way with gestures and smiles. Later there was farmed land, with villages, and a couple of towns, where he paid for his needs from the slave master’s purse, and finally, twenty-seven days after his escape, he came to Dassun.

The city was walled but the gates unguarded. Inside it seemed planless, tiny thronged streets, with gaudy clothes and parasols, all the reeks and sounds of commerce and humanity: houses a mixture of brick, timber, plaster, mud and whatnot, often several storeys high; the people’s faces almost black, lively and expressive; vigorous hand-gestures aiding speech; the fullness of life, the sort of life that Varro relished.

He let his feet tell him where to go and found himself in an open marketplace, noisier even than the streets—craftsmen’s booths, merchants’ stalls of all kinds grouped by what they sold, fruit, fish, meat, grain, gourds, pottery, baskets and so on. Deliberately now, he sought out the leatherworkers’ section.

He approached two stall-holders, both women, and showed them his tools, and with obvious gestures made it clear that he was looking for work. Smiling, they waved him away. The third he tried was an odd-looking little man, a dwarf, almost, fat and hideous, but smiling like everyone else. He would have fetched a good price as a curiosity in any northern slave market. He chose a plain purse from his stall, picked a piece of leather from a pile, gave them to Varro and pointed to an empty patch of shade beneath his awning. Varro settled down to copy the purse, an extremely simple task, so for his own pleasure as well as to show what he could do he put an ornamental pattern into the stitching. When the stall-holder came back to see how he was getting on, Varro showed him the almost finished purse. The stall-holder laughed aloud and clapped him on the shoulder. He pointed at his chest.

“Andada,” he said.

“Andada,” Varro repeated, and then tapped his chest in turn and said “Varro.”

“Warro,” the man shouted through his own laughter, and clapped Varro on the shoulder again. Varro was hired.

That night Andada took him home and made him eat with his enormous family—several wives and uncountable children, each blacker than the last, and gave him a palliasse and blanket for his bed. The children seemed to find their visitor most amusing. Varro didn’t mind.

Over the next few days, sitting in his corner under the awning and copying whatever Andada asked him to, Varro shaped and stitched out of scraps of leather a miniature saddle and harness, highly ornate, the sort of thing apprentices were asked to do as a test-piece before acceptance into the Guild.

Andada, when he showed it to him, stopped smiling. He took the little objects and turned them to and fro, studying every stitch, then looked at Varro with a query in his eyes and made an expansive gesture with his hands. Varro by now had learnt some words of the language.

“I make big,” he confirmed, and sketched a full-size saddle in midair.

Andada nodded, still deeply serious, closed his stall, and gestured to Varro to follow him. He led the way out of the market, through a tangle of streets, into one with booths down either side. These clearly dealt in far more expensive goods than those sold in the market, imported carpets, gold jewellery set with precious gems, elaborate glassware, and so on. Halfway up it was a saddler’s shop, again filled with imports, many the standard Timbuktu product, manufactured for trade and so gaudy but inwardly shoddy—a saddler who produced such a thing for Prince Fo would have been flogged insensible.

Andada gripped Varro’s elbow to prevent him moving nearer.

“You make?” he whispered. Varro nodded, and they went back to the market. He spent an hour drawing sketches of different possible styles. Andada chose three, then took Varro to buy the materials, casually, from different warehouses, among other stuff he needed for his normal trade. Varro watched with interest. From his experience with the guild in Timbuktu he saw quite well what was happening. There was good money in imported saddles. Andada by making them on the spot could undercut the importers with a better product. The importers would not like it at all.

Andada was a just man, as well as being a cautious one. Having done a deal that allowed one of the importers to conceal the provenance of Varro’s saddles, and leave a handsome profit for both men, he started to pay Varro piecework rather than a wage, at a very fair rate, allowing Varro to rent a room of his own, eat and drink well, and for the moment evade the growing prospect of finding himself married to one or more of Andada’s older daughters. He started to enjoy himself. He liked this city, its cooking, its tavern life, its whole ethos, exotic but just as civilised as Ravenna, in its own way. So as not to stand out he adopted the local dress, parasol, a little pill box hat, thigh-length linen overshirt, baggy trousers gathered at the ankle . . .

But not the slippers. While his fellow citizens slopped in loose-heeled flip-flops, he stuck to the gryphon-hide boots he had made for himself in the desert. They were the only footwear he now found comfortable, so much so that on waking he sometimes found that he had forgotten to take them off and slept in them all night. Presumably, in the course of that last hideous stretch to the gryphon’s pool, he had done some kind of harm to his feet, from which they had only partially recovered—indeed, unshod, they were still extremely tender—but had managed to adapt themselves to the gryphon boots during the long march out of the desert. It was almost two months before he discovered that there was more to it than that.

Unnoticed at first, he had begun to feel a faint tickling sensation on the outside of both legs, just below the top of the shoes at the back of the ankle bone. He became conscious of it only when he realised that he had developed a habit of reaching down and fingering the two places whenever he paused from his work. The sensation ceased as soon as he unlaced the boots and felt beneath, but though he could find nothing to cause it on the inside of the boots themselves, it returned as soon as he refastened them. It was not, however, unpleasant—the reverse, if anything—so he let it be and soon ceased to notice it.

So much so that it must have been several days before he realised that the sensation was gone. He explored, and found that where it had been there was now a small but definite swelling in the surface of the boots, but nothing to show for it when he felt beneath, apart, perhaps, from a slightly greater tenderness of his own skin at those two places. The swellings had grown to bumps before the first downy feathers fledged.

He studied them, twisting this way and that to see them, and then sat staring at nothing.

Talaria, he thought. The winged boots of the God Mercury. Impossible. But nothing is impossible to a god. Talaria. Mine.

Varro’s attitude to the gods had always been one of reasoned belief. He didn’t think, suppose he had been ushered into the unmitigated presence of a deity, and unlike Semele could endure that presence, that he would have seen a human form, or heard a voice speaking to him through his ears. Whatever he might have seen and heard he would done so inside his head. The human shape and speech were only a way for him to be able to envisage the deity and think about him. Similarly with the talaria. Suppose Mercury had chosen to appear to him in human form, he would have done so with all his powers and attributes expressed in his appearance, including that of moving instantaneously from one place to another. The talaria were, so to speak, a divine metaphor. Now the god was presenting him with a real pair. To what end? So that when the wings had grown he could fly instantaneously back to Ravenna? He wasn’t sure that he wanted to. He liked it here.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Earth and Air»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Earth and Air» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Earth and Air» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.