Mark Changizi - Harnessed - How Language and Music Mimicked Nature and Transformed Ape to Man

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Mark Changizi - Harnessed - How Language and Music Mimicked Nature and Transformed Ape to Man» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 2011, Издательство: Perseus Books Group, Жанр: Старинная литература, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Harnessed: How Language and Music Mimicked Nature and Transformed Ape to Man

- Автор:

- Издательство:Perseus Books Group

- Жанр:

- Год:2011

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:5 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Harnessed: How Language and Music Mimicked Nature and Transformed Ape to Man: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Harnessed: How Language and Music Mimicked Nature and Transformed Ape to Man»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

Harnessed: How Language and Music Mimicked Nature and Transformed Ape to Man — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Harnessed: How Language and Music Mimicked Nature and Transformed Ape to Man», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

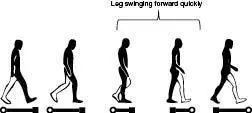

Your legs are a pair of 25-pound pendulums that swing forward as you move, and are the principal sources of your between-the-steps hit sounds. A close look at how your legs move when walking (see Figure 41) will reveal why between-the-step hits are more likely to occur just before a footstep than just after. Get up and take a few steps. Now try it in slow motion. Let your leading foot hit the ground in front of you for its step. Stop there for a moment. This is the start of a step-to-step interval, the end of which will occur when your now-trailing foot makes its step out in front of you. Before continuing your stride, ask yourself what your trailing foot is doing. It isn’t doing anything. It is on the ground. That is, at the start of a step-to-step interval, both your feet are planted on the ground. Very slowly continue your walk, and pay attention to your trailing foot. As you move forward, notice that your trailing foot stays planted on the ground for a while before it eventually lifts up. In fact, your trailing foot is still touching the ground for about the first 30 percent of a step-to-step interval. And when it finally does leave the ground, it initially has a very low speed, because it is only just beginning to accelerate. Therefore, for about the first third of a step, your trailing foot is either not moving or moving so slowly that any hit it does take part in will not be audible. Between-the-footsteps hit sounds are thus relatively rare immediately after a step. After this slow-moving trailing-foot period, your foot accelerates to more than twice your body speed (because it must catch up and pass your body). It is during this central portion of a step cycle that your swinging leg has the energy to really bang into something. In the final stage of the step cycle, your forward-swinging leg is decelerating, but it still possesses considerable speed, and thus is capable of an audible hit.

Figure 41. Human gait. Notice that once the black foot touches the ground (on the left in this figure), it is not until the next manikin that the trailing (white) foot lifts. And notice how even by the middle figure, the trailing foot has just begun to move. During the right half of the depicted time period, the white leg is moving quickly, ready for an energetic between-the-steps hit on something.

We see, then, that there is a fundamental temporal asymmetry to the human step cycle. Between-the-steps hits by our forward-swinging leg are most probable at the middle of the step cycle, but there is a bias toward times nearer to the later stages of the cycle. In Figure 41, this asymmetry can be seen by observing how the distance between the feet changes from one little human figure to the next. From the first to the second figure there is no change in the distance between the feet. But for the final pair, the distance between the feet changes considerably. For human gait, then, we expect between-the-steps gangly hits as shown in Figure 42a: more common in mid-step than the early or late stages, and more common in the late than the early stage.

Figure 42. (a)Because of the nature of human gait, our forward-swinging leg is most likely to create an audible between-the-steps bang near the middle of the gait cycle, but with a bias toward the late portions of the gait cycle, as illustrated qualitatively in the plot. (b)The relative commonness of between-the-beat notes occurring in the first half (“early”), middle, or second half (“late”) portions of a beat cycle. One can see the qualitative similarity between the two plots.

Does music show the same timing of when between-the-beat notes occur? In particular, are between-the-beat notes most likely to occur at about the temporal center of the interval, with notes occurring relatively rarely at the starts and ends of the beat cycle? And, additionally, do we find the asymmetry that off-beat notes are more likely to occur late than early (i.e., are long-shorts more common than short-longs)? This is, indeed, a common tendency in music. One can see this in the classical themes as well, where I measured intervals from the first 550 themes in Barlow and Morgenstern’s dictionary, using only themes in 4/4 time. There were 1078 cases where the beat interval had a single note directly in the center, far more than the number of beat intervals where only the first or second half had a note in it. And the gaitlike asymmetry was also found: there were 33 cases of “short-longs” (beat intervals having an off-beat note in the first half of the interval but not the second half, such as a sixteenth note followed by a dotted eighth note), and 131 cases of “long-shorts” (beat intervals having a note in the second half of the interval but not the first half, like a dotted eighth note followed by a sixteenth note). That is, beat intervals were four times more likely to be long-short than short-long, but both were rare compared to the cases where the beat interval was evenly divided. Figure 42b shows these data.

Long-shorts are more common in music because they perceptually feel more natural for movement—because they are more natural for movement. And, more generally, the time between beats in music seems to get filled in a manner similar to the way ganglies fill the time between steps. In the Chapter 4 section titled “The Length of Your Gangly,” we saw that beat intervals are filled with a human-gait-like number of notes, and now we see that those between-the-beat notes are positioned inside the beat in a human-gait-like fashion.

Thus far in our discussion of rhythm and beat, we have concentrated on the temporal pattern of notes. But notes also vary in their emphasis. As we mentioned earlier, on-beat notes typically have greater emphasis than between-the-beat notes, consistent with human movers typically having footsteps more energetic than their other gangly bangs. But even notes on the beat vary in their emphasis, and we take this up next.

2 Measure of What?

Thus far we have discussed beats as footsteps, and between-the-beat notes as between-the-footsteps banging ganglies. But there are other rhythmic features of music that occur at the scale of multiple beats. In particular, music rarely treats each and every beat as equal. Some beats are special. In ¾ time, for example, every third beat gets a little emphasis, and in 4/4 time every fourth beat gets an emphasis. This is the source of the measure in music, where the first beat in each measure gets the greatest emphasis. (And there are additional patterns: in 4/4 time, for instance, the third beat gets a little extra oomph, too, roughly half that of the first.) If you keep the notes of a piece of music the same, but modify which beats are emphasized, the song can often sound nearly unrecognizable. For example, here is “Twinkle, Twinkle Little Star,” but with some unusual syllables emphasized to help you sing it in ¾ time rather than the appropriate 4/4 time. “ TWI -nkle, twi- NKLE, lit-tle STAR , , how I won-der WHAT you are.” As you can see, it is very challenging to even get yourself to sing it in the wrong time signature. And when you eventually manage to do it, it is a quite different song from the original.

Why should a difference in the pattern of emphasis on beats make such a huge difference in the way music sounds to us? With the movement theory of music in hand, the question becomes: does a difference in the pattern of emphasis of a mover’s footsteps make a big difference in the meaning of the underlying behavior? For example, is a mover with a ¾ time gait signature probably doing a different behavior than a mover with a 4/4 time gait signature?

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Harnessed: How Language and Music Mimicked Nature and Transformed Ape to Man»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Harnessed: How Language and Music Mimicked Nature and Transformed Ape to Man» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Harnessed: How Language and Music Mimicked Nature and Transformed Ape to Man» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.