Mark Changizi - Harnessed - How Language and Music Mimicked Nature and Transformed Ape to Man

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Mark Changizi - Harnessed - How Language and Music Mimicked Nature and Transformed Ape to Man» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 2011, Издательство: Perseus Books Group, Жанр: Старинная литература, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Harnessed: How Language and Music Mimicked Nature and Transformed Ape to Man

- Автор:

- Издательство:Perseus Books Group

- Жанр:

- Год:2011

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:5 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Harnessed: How Language and Music Mimicked Nature and Transformed Ape to Man: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Harnessed: How Language and Music Mimicked Nature and Transformed Ape to Man»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

Harnessed: How Language and Music Mimicked Nature and Transformed Ape to Man — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Harnessed: How Language and Music Mimicked Nature and Transformed Ape to Man», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

How about the second hurdle for a theory of music, the one labeled “emotion”? Could the mundane sounds of people moving underlie our love affair with music? As we discussed at the start of the chapter, music is evocative—it can sound joyous, aggressive, melancholy, amorous, tortured, strong, lethargic, and so on. I said then that the evocative nature of music suggests that it must be “made out of people.” Human movement is , obviously, made of and by people, but can human movement truly be evocative? Of course! The ability to infer emotional states from the bodily movements of others comes via several routes. First and foremost, when people carry out behaviors they move their bodies, movements that can give away what the person is doing; knowing what the person is doing can, in turn, be crucial for understanding the actor’s emotion or mood. Second, the actor’s emotional state is often cued by its side effects on behavior, such as when an exhausted person staggers. And third, some bodily movements serve as direct emotional signals, more akin to facial expressions and color signals: bodily movements can be proud, strutting, threatening, ebullient, jaunty, sulking, arrogant, inviting, and so on. Human movement can, then, certainly be evocative. And unlike evocative facial expressions and skin color signals, which are silent, our evocative bodily expressions and movements make noises. The sounds of human movement not only are “made from people,” then, but they can be truly evocative, fulfilling the “emotion” hurdle.

An example will help to clarify how the sounds of human movement can be emotionally evocative. Michael Zampi, then an undergraduate at RPI, was interested in uncovering the auditory cues for happy, sad, and angry walkers. He first noted that University of Tübingen researchers Claire L. Roether, Lars Omlor, Andrea Christensen, and Martin A. Giese had observed that happy walkers tend to lean back and have large arm and leg swings, angry walkers lean forward and have large arm and leg swings, and sad walkers tend to lean forward and have attenuated arm and leg swings.

“What,” Michael asked, “are the distinctive sounds for those three gaits?” He reasoned that leaning back leads to a larger gap between the sound of the heel and the sound of the toe. And, furthermore, larger arm and leg swings tend to lend greater emphasis to any sounds made by the limbs in between the footsteps (later I will refer to these sounds as “banging ganglies”). Given this, Michael could conclude that happy walkers have long heel-toe gaps and loud between-the-steps gait sounds; angry walkers have short heel-toe temporal gaps and loud between-the-steps gait sounds; and sad walkers have short heel-toe gaps and soft between-the-steps gait sounds. But are these cues sufficient to elicit the perception that a walker is happy, angry, or sad?

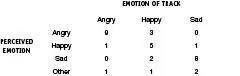

Michael created simple rhythms, each with three drum strikes per beat: a toe-strike on the beat, a heel strike just before the beat, and a between-the-step hit on the off-beat. Starting from a baseline audio track—an intermediate heel-toe gap and a between-the-steps sound with intermediate emphasis—Michael created versions with shorter and longer heel-toe gaps, and versions with less emphasized and more emphasized between-the-steps sounds. Listeners were told they would hear the sounds of people walking in various emotional states, and then the listeners were presented with the baseline stimulus, followed by one of the four modulations around it. They were asked to volunteer an emotion term to describe the modulated gait. As can be seen in Figure 17, subjects had a tendency to perceive the simulated walker’s emotion accurately.

Figure 17. Each column is for one of the three tracks having the sounds modulating around the baseline to indicate the labeled emotion. The numbers show how many subjects volunteered the emotions “angry,” “happy,” “sad,” or other emotions words for each of the three tracks. One can see that the most commonly perceived emotion in each column matches the gait’s emotion.

This pilot study of Michael Zampi’s is just the barest beginning in our attempts to make sense of the emotional cues in the sounds of people moving. The hope is that by understanding these cues, we can better understand how music modulates emotion, and perhaps why genres differ in their emotional effects.

If music has been culturally selected to sound like human movement, then it is easy to see why we’d have a brain for it, and easy to see why music can be so emotionally moving. But why should music be so motionally moving? The music-is-movement theory has to explain why the sounds of people moving should impel other people to move. That’s the third hurdle over which we must leap: the “dance” hurdle, which we take up next.

Motionally Moving

Group activities with toddlers are hopeless. Just as you get the top toddler into position at the peak of the toddler pyramid, several on the bottom level have begun crying, pooping, or wandering away. Toddlers prefer to treat their day-care mates as objects to ignore, climb over, or hit. And just try getting a dozen of them to do anything in unison, like performing “the wave” in the audience at a roller derby! If aliens observed us humans only during toddlerhood, they might conclude that we don’t get on well in groups, and that, lacking a collaborative spirit, we will be easy prey when they invade.

But brain-thirsty aliens might come to a very different conclusion if they dropped in on a day-care center during music time. Flip on “The Wheels on the Bus Go Round and Round,” and a dozen randomly wandering, cantankerous droolers begin shaking their stinky bottoms in unison. Aliens might surmise that music is some kind of marching order, a message from the human commander to activate gyrations against an invading enemy.

Dancing toddlers, of course, play little or no role in explaining why we haven’t been invaded by aliens, but they do raise an important question. Why do toddlers seem to be compelled to move to the music? And, more generally, why is this a tendency we keep into adulthood? At this very moment of writing, I am, in fact, swaying slightly to Tchaikovsky’s Piano Concerto No. 1. Don’t I have better things to do? Yes, I do—like write this book. Yet I keep pausing to hear the music, and end up ever so slightly dancing. It is easy to understand why people dance when a gun is fired at their feet like in old Westerns, but music is so much less substantial than lead, and yet it can get us going as surely as a Colt 45. What is the source of music’s power to literally move us, like rats to the Pied Piper’s flute?

We can make sense of this mystery in light of the theory that music sounds like human movement. If music sounds like movement, and music makes us move, then it is not so much music that is making us move, but the sound of human movement. And that’s not at all mysterious! Of course the behaviors of others may elicit responsive actions from us. For example, if my three-year-old son barrels headlong toward my groin, I quickly move my hands downward for protection. If he throws a rubber ball at my head, I try to catch it. And if he suddenly decides he’d rather not wear his bathing shorts, I quickly pull them back up. Not only do I behave in reaction to my son’s behavior, but my behavior must be timed appropriately, lest he careen into me, bean me with a ball, or strip buck-naked and get a head start in his dash away. Music sounds like human behavior, and human behavior often elicits appropriately timed behavioral responses in others, so it is not a surprise, in light of the theory, that music elicits appropriately timed behavioral responses.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Harnessed: How Language and Music Mimicked Nature and Transformed Ape to Man»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Harnessed: How Language and Music Mimicked Nature and Transformed Ape to Man» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Harnessed: How Language and Music Mimicked Nature and Transformed Ape to Man» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.