Mark Changizi - Harnessed - How Language and Music Mimicked Nature and Transformed Ape to Man

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Mark Changizi - Harnessed - How Language and Music Mimicked Nature and Transformed Ape to Man» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 2011, Издательство: Perseus Books Group, Жанр: Старинная литература, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Harnessed: How Language and Music Mimicked Nature and Transformed Ape to Man

- Автор:

- Издательство:Perseus Books Group

- Жанр:

- Год:2011

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:5 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Harnessed: How Language and Music Mimicked Nature and Transformed Ape to Man: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Harnessed: How Language and Music Mimicked Nature and Transformed Ape to Man»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

Harnessed: How Language and Music Mimicked Nature and Transformed Ape to Man — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Harnessed: How Language and Music Mimicked Nature and Transformed Ape to Man», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

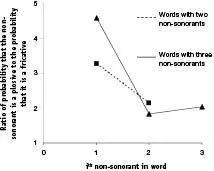

Figure 9. This shows how plosives are more probable at the start of words, and fall in probability after the start. The y-axis shows the plosive-to-fricative ratio, and the x-axis the ith non-sonorant in a word. The dotted line is for words with two non-sonorants, and the solid line for words with three non-sonorants. The main points are (i)that plosives are always more probable than fricatives, as seen here because the plosive-to-fricative probability ratios are always greater than 1, and (ii)that the ratio falls after the start of the word, meaning fricatives are disproportionately rare at word starts. These data come from common words (typically about a thousand) from each of the following languages: Japanese, Zulu, Malagasy, Somali, Fijian, Lango, Inuktitut, Bosnian, Spanish, Turkish, English, German, Bengali, Yucatec, Wolof, Tamil, Taino, Haya.

We just concluded that hits are disproportionately common at the starts of events in nature, and that this feature is also found in language. But we ignored rings. Where in events do rings tend to reside? In the previous section (“Nature’s Syllables”) we discussed the fact that rings do not start events, a phenomenon also reflected in language. How about after the start of a word? There would appear to be a simple answer: rings always occur after physical interactions, and so rings should appear at all spots within events, following each hit or slide.

But as we will see next, reality is more subtle.

The First Was a Doozy

While it is true that all physical interactions cause ringing, the ringing need not be audible, a point that already came up in the section called “Two-Hit Wonder.” In this light, we need to ask, where in events are the rings most audible ? Consider the generic pen-on-table event again. The beginning of that event—the audible portion of it, starting when the pen hit the table—is where the greatest energy tends to be, and the ring sound after the first hit will therefore tend to be the loudest. If the pen bounces and hits the table again, the ring sound will be significantly lower in magnitude, and it will be lower still for any further bounces. Because energy tends to get dissipated during the course of an event, rings have a tendency to be louder earlier in the event than later in the event. This is a tendency, but it is not always the case. If energy gets added during the event, ring magnitude can increase. For example, if your pen bounces a couple of times on the table, but then bounces off the table onto the floor, then the floor hit may well be louder than the first table hit (gravity is the energy-adding culprit). Nevertheless, in the generic or typical case, energy will dissipate over the course of a physical event, and thus ringing magnitude will tend to be reduced as an event unfolds. Therefore, the audibility of a ring tends to be higher near the start of an event; or, correspondingly, the probability is higher later in an event that a ring might not be audible.

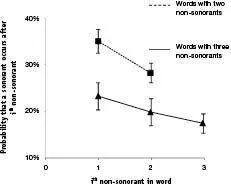

If language is instilled with physics, we would accordingly expect that sonorant phonemes are more likely to follow a plosive or fricative near the start of a word, and are more likely to go missing near the end of a word. This is, in fact, the case. Figure 10 shows how the probability of a sonorant following a non-sonorant falls as one moves further into a word, using the same data set mentioned earlier. For example, words like “pact” are not uncommon in English, but words like “ctap” do not exist, and are rare in languages generally.

Figure 10. This shows that sonorant phonemes are more probable near the starts of words, namely just after the first non-sonorant (usually a plosive). The square data are for words having two non-sonorants, and the triangle data for words having three non-sonorants.

We have begun to get a grip on how hits, slides, and rings occur within events, but we have only considered their probability as a function of how far into the event they occur. In real events there will be complex dependencies, so that if, say, a slide occurs, it changes the probability of another slide occurring next. In the next section we’ll ask, more generally, which combinations of hits and slides are common and which are rare, and then check for the same patterns in language.

Nature’s Words

Rube Goldberg machines excel at producing very long events, all part of a single causal chain. Like most events, Rube Goldberg events are built mostly out of hits, slides, and rings. Again letting b , s , and a stand for hits, slides, and rings, Rube Goldberg events sound something like basabababasababababababasabababasa , although the chains are very often much longer than even this. If events were typically like Rube Goldberg events, then even if spoken words have many of the auditory features found in events, words would be much too short to be event-like. Events are, however, not typically Rube Goldberg-like. Events are, instead, much more typically like a pen thrown on a table, the generic event we discussed in the previous section. Pen-on-table events may consist of a hit, hit, and slide. Or possibly just a hit and a slide. Or even just a lone hit. Most events have just several physical interactions or fewer, much nearer in length to spoken words than to Rube Goldberg events.

This is what nature-harnessing expects. Spoken words across human languages are not only built out of sounds like those in solid-object physical events, but words tend to have the size of typical physical events. Words tend to sound like events with up to several interaction sounds—plosives or fricatives—not, say, ten. And although words with a single interaction sound are allowed, two or three interaction sounds are more common, again like solid-object physical events.

Words are not only approximately the size of solid-object physical events—i.e., having several interaction sounds—words also take the amount of time for a typical event. This is something I have thus far ignored. But notice that plosives, fricatives, and rings do not just have similar acoustic characteristics to hits, slides, and rings; they also occur over periods of time similar to those typical of hits, slides, and rings. For example, although I described both hits and plosives as nearly instantaneous explosions, the notion of “instantaneous” depends on the time scale relevant to the listener—what’s instantaneous to a human may not be instantaneous to a fly. Hits and plosives are both instantaneous explosions as heard by human ears. This is why plosives sound hitlike; for example, if a hitlike sound were stretched out it would, instead, sound more slidelike (something we discussed in the earlier section called “Hesitant Hits”). Similarly, fricatives and sonorants tend to occur over time scales similar to the slides and rings of physical events. Typical syllables of human speech—e.g., of the form ba or sa —tend to have a duration approximately on the order of tenths of seconds, roughly the same time scale as is common for physical events involving macroscopic objects. In fact, you’ll notice in Figure 4 earlier that the physical and linguistic analogs (e.g., a hit and “k”) are on the same scale for the time (x) axis.

Words tend to be built out of the constituents of natural solid-object physical events, and to have approximately the size and temporal duration of such events. But are words actually structured like solid-object physical events? Are the natural-sounding phonemes and syllables put together into natural-sounding words? In particular, I’m interested in asking whether the sequences of physical interactions that occur in events—the hits and slides—are similar to the sequences of plosives and fricatives in words. My students and I analyzed the “event structure” of common words across 18 languages, and for each language we measured the distribution of six event types: hit ( b ), slide ( s ), hit-hit ( bb ), hit-slide ( bs ), slide-hit ( sb ), and slide-slide ( ss ). For example, “tea” is a b , “far” is an s , and “faker” is an sb .

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Harnessed: How Language and Music Mimicked Nature and Transformed Ape to Man»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Harnessed: How Language and Music Mimicked Nature and Transformed Ape to Man» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Harnessed: How Language and Music Mimicked Nature and Transformed Ape to Man» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.