Mark Changizi - Harnessed - How Language and Music Mimicked Nature and Transformed Ape to Man

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Mark Changizi - Harnessed - How Language and Music Mimicked Nature and Transformed Ape to Man» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 2011, Издательство: Perseus Books Group, Жанр: Старинная литература, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Harnessed: How Language and Music Mimicked Nature and Transformed Ape to Man

- Автор:

- Издательство:Perseus Books Group

- Жанр:

- Год:2011

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:5 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Harnessed: How Language and Music Mimicked Nature and Transformed Ape to Man: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Harnessed: How Language and Music Mimicked Nature and Transformed Ape to Man»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

Harnessed: How Language and Music Mimicked Nature and Transformed Ape to Man — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Harnessed: How Language and Music Mimicked Nature and Transformed Ape to Man», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

But there are implications to the fact that slides are built from very many hits, but not vice versa: that fact opens up the possibility of a fundamental event type that is not quite a hit, and not quite a slide. To understand this new event type, let’s look at a slide at the level of its million underlying hits. Imagine that the first of these million hits is appreciably more energetic than the others. If this were the case, then the start of the slide would acquire a crispness normally found in hits. But this hit would be just the first of a long sequence of hits, and would thus be part of the slide itself. Such a hit-slide would, if it existed, be neither a hit nor a slide.

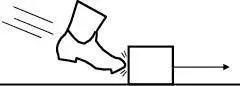

And they do exist, for several converging reasons. First, slides have a tendency to be initiated by hits. Try sliding this book on a desk. The first time you tried, you may have bumped your hand into the book in the process of attempting to make it slide. That is, you may have hit the book prior to the slide (see Figure 5). It requires careful attention to gently touch the book without hitting it first. Now grab hold of the book and try to slide it without an initial hit. Even in this case there can often be an initial hitlike event. This is because in order to slide an object, you must overcome static friction, the “sticky” friction preventing the initiation of a slide. This initial push is hitlike because the sudden overcoming of static friction creates a sudden burst of many frequencies, as in Figure 4a. Slides, then, often begin with a hit. Second, hits often have slides following them. If you hit a wall with a straight jab, you will get a lone hit, with no follow-up slide. But if you move your arm horizontally next to the wall as you are hitting it—in order to give it a more glancing blow—there will sometimes be a small skid, or slide, after the initial hit.

Figure 5. A hit-slide is a fourth fundamental constituent of physical events. It sounds like a kind of phoneme in language called the affricate, which is like a plosive followed by a fricative.

Although a hit followed by a slide is a natural regularity in the world, a slide followed by a hit is not a natural physical regularity. First, it is common to have a hit not preceded by a slide. To see this, just hit something. Odds are you managed to make a hit without a slide first. Second, when there is a slide, there is no physical regularity tending to lead to a hit. Slides followed by hits are possible, of course—in shuffleboard, for example (and note the fricatives in “shuffle”)—but they really are two separate events in succession. A hit-slide, on the other hand, can effectively be a single event, as we discussed a moment ago.

If language sounds like nature, then we should expect linguistic hit-slide sounds to be more common than slide-hit sounds. Later in this chapter—in the section titled “Nature’s Words”—I will provide evidence that this is true of the way phonemes combine into words across human languages. But in this section I want to focus on the single-phoneme level. The question is, since hit-slides are a special kind of fundamental event atom, but slide-hits are not, do we find that languages have phonemes that sound like hit-slides, but not phonemes that sound like slide-hits?

Languages, like nature, are asymmetrical in this way. There is a kind of phoneme found in many languages called an affricate , which is a fricative that begins as a plosive. One example in English is “ch,” which is a single phoneme that possesses a “t” sound followed by a “sh” sound. In addition to words like “chair,” it also occurs in words like “congratulate” (spoken like “congratchulate”), and often in words like “trash” (spoken like “chrash”). Another example is “j,” which begins with “d” sound followed by a voiced version of the “sh” phoneme. Although we can describe “ch” as a “sh” initiated by a “t,” it is not the same sound that occurs when we say “t” and quickly follow it up with “sh.” The “ch” phoneme has the “t” and “sh” sounds bound up so closely to one another that they sound like a single atomic event. The “tsh” sound in “hotshot,” on the other hand, will typically sound different from “ch”; that is, we do not pronounce the word “ha-chot.”

Whereas language has incorporated nature’s hit-slide phoneme as one of its phoneme types, slide-hits, on the other hand, are not one of nature’s phonemes, and a harnessing language is not expected to have phonemes that sound like slide-hits. Indeed, that is the case. Languages do not have the symmetric counterpart to affricates—phonemes that sound like a plosive initiated by a fricative. It is not that we can’t make such sounds—“st” is a standard sound combination in English of this slide-hit form, but it is not a single phoneme. Other cases would be the sounds “fk” and “shp,” which occur as pairs of phonemes in words in some languages, but not as phonemes themselves.

By examining physics in greater detail, in this section we have realized that there is a fourth fundamental building block of events: hit-slides. And just as languages have honored the other three fundamental event atoms as their principal phoneme types, this fourth natural event atom is also so honored. Furthermore, the symmetrical fifth case, slide-hits, is not a fundamental event type in nature, and we thus expect—if harnessing has occurred—not to find fricative-plosives as language phonemes. And indeed, we don’t find them.

Slides that Sing

Recall that slides are, in essence, built from very many little hits in quick succession. The pattern of hits occurring inside a slide depends on the nature of the materials sliding together, and this pattern is what determines the nature of the slide’s sound. If you scrape your pencil on paper, then because the paper’s microscopic structure is fairly random, the sound resulting from the many little hits is a bit “noisy,” or like radio static, in having no particular tone to it. (The pencil scraping may also cause some ringing in the table or the pencil, but at the moment I want you to concentrate only on the sound emanating from the slide itself.)

However, now unzip your pants. You just made another slide. Unlike a pencil on paper, however, the zipper’s regularly spaced ribs create a slide sound that has a tonality to it. And the faster you unzip it, the higher the pitch of the zip. Slides can sing. That is, slides can have a ringlike quality to them, due not to the periodic vibrations of the objects, but to the periodicity in the many tiny hits that make up a slide.

Whether or not a slide sings depends on the nature of the materials involved, and that’s why the voice of a slide is an auditory feature that brains have evolved to take notice of: our brains treat singing and hissing slides as fundamentally different because these differences in slide sounds are informative as to the identity of the objects involved in the slides. Although slides can sing, it is more common that they don’t, because texture with periodicity capable of a ringlike sound is rare, compared to random texture that leads to generic friction sounds akin to white noise.

Do human languages treat singing slide sounds as different from otherwise similar nonsinging slide sounds? Yes. Languages have fricatives of both the singing and the hissing kinds, called the voiced and unvoiced fricatives, respectively. Voiced fricatives include “z,” “v,” “th” as in “the,” and the sound after the beginning of “j” (which you will recall is an affricate, discussed earlier in “Nature’s Other Phoneme”). Unvoiced fricatives include “s,” “f,” “th” as in “thick,” and “sh.” Just as singing slides will be rarer than nonsinging slides—because the former require special circumstances, namely, slides built out of many periodically repeating hits—voiced fricatives are rarer in languages than unvoiced fricatives. John L. Locke tabulated data in his excellent 1983 book, Phonological Acquisition and Change , and discovered that “s” is found in 172 of 197 languages in the Stanford Handbook[1] (87 percent) and in 102 of 317 languages in the UCLA Phonological Segment Inventory Database (32 percent), whereas “z” (the voiced version of “s”) is found in 77 of 197 languages (39 percent) and 36 of 317 languages (11 percent), respectively. Similarly, “f” is found in 106 of 197 languages (54 percent) and in 135 of 317 languages (43 percent), whereas “v” is found in 61 of 197 languages (31 percent) and in 67 of 317 languages (21 percent), respectively. These data suggest that unvoiced slides are about twice as likely as voiced slides to be found in a language. (And notice how, in English at least, one finds voiced-fricative words with meanings related to slides that sing: rev, vroom, buzz, zoom, and fizz. One also finds unvoiced-fricative words with meanings related to unsung slides: slash, slice, and hiss.)

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Harnessed: How Language and Music Mimicked Nature and Transformed Ape to Man»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Harnessed: How Language and Music Mimicked Nature and Transformed Ape to Man» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Harnessed: How Language and Music Mimicked Nature and Transformed Ape to Man» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.