Robert Nye - The Late Mr Shakespeare

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Robert Nye - The Late Mr Shakespeare» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 2012, ISBN: 2012, Издательство: Allison & Busby, Жанр: Старинная литература, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:The Late Mr Shakespeare

- Автор:

- Издательство:Allison & Busby

- Жанр:

- Год:2012

- ISBN:9780749012205

- Рейтинг книги:5 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

The Late Mr Shakespeare: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «The Late Mr Shakespeare»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

The Late Mr Shakespeare — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «The Late Mr Shakespeare», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

But think of what I'm saying. John Shakespeare was a drunkard. He was fat. He was witty. He spent most of his time in the ale-house. He told lies. He rose Alderman-high* in Stratford before he fell ruffian-low. The boy William's first memories of him would have been of a great man in a red gown with white ermine collar and trimmings. And John's fall from grace must have come in William's youth. I am sure John Shakespeare cast a long shadow over his son's life. Yes, and a fat shadow too, I'm convinced of that.

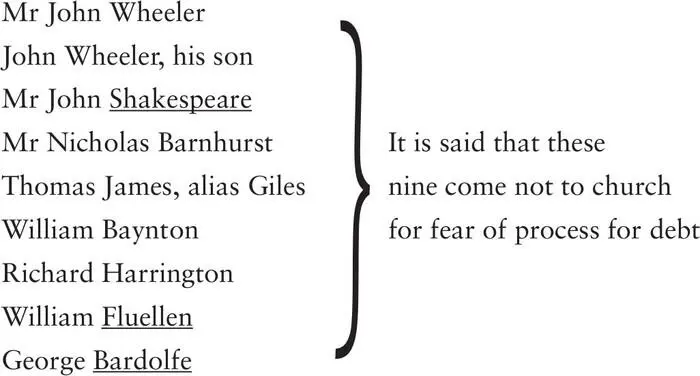

But don't take my word for it. Look at the names on this black list. It's a list that I turned up in Stratford - of men not attending Trinity Church in the year of 1592:

I have underlined the three names that prove there must be something to my case. Here we see John Shakespeare linked in disrepute with two of Falstaff's cronies: Bardolph and Fluellen. Of the real-life Fluellen I know nothing, save that his widow died in the Stratford almhouse. But George Bardolfe was much like the rogue in the plays - in Henry IV, Henry V, and The Merry Wives of Windsor . He started as a mercer and a grocer, and ended up as a drunk. Writs of arrest were issued against him for debt. He was imprisoned for it in the year he appeared on the list. They say he had friends in high places, and that the under-sheriff of Warwickshire, Basil Trymnell, let this Bardolfe out to drink in a tavern in Warwick but when warned that he might escape kept him 'in a much straighter manner' and secured him by 'a lock with a long iron chain and a great clog'.

The character and nature of John Shakespeare and his associates seems to me as near a match as you will find for the character and nature of John Falstaff and his associates. Who says the people in the plays are not real people? I think they had flesh and blood in our poet's mind.

Besides which, Thomas Plume, the Archdeacon of Rochester, told me that Sir John Mennis once saw Mr John Shakespeare in his shop in Henley Street. This would have been at the end of the last century. He was a merry-cheeked old man, he said. He said also that the father said that Will was 'a good honest fellow', but he 'durst have cracked a jest with him at any time'. Who else can this remind you of but Falstaff and Prince Hal? Do thou stand for my Father , as the poet has the prince say true to Falstaff.

I should not be surprised one day to learn that John Shakespeare died crying out 'God, God, God', as Mistress Quickly says John Falstaff did. Some say he died a Papist, like his son. But more of that later.

That hubbub's an Irish war-cry: Ub! Ub! Ubub!

As for Doctor Timothy Bright, he was a very fine physician in his day, and the odious Bretchgirdle's invoking him should in no wise be permitted to detract from his excellent fame. In addition to his treatise on preserving health, called Hygieina , he wrote a good one on restoring the same commodity, Therapeutica . He also invented a shorthand system that was used by Robert Cecil and his spies. His Treatise of Melancholy , published in 1586, distinguishes between the mental and the physical roots of that affliction. The late Mr Shakespeare was fond of this little book. I often saw him reading in it, and he may even have derived from thence the phrase 'discourse of reason' which comes in Hamlet's first soliloquy.

I doubt myself that Dr Bright ever poured bile on any carpet. Nor would Grindal have blessed a bottle. He leant towards Geneva in such matters.

I met John Shakespeare myself, but just the once. I'll be telling you all about that when we come to it.

* Falstaff in Henry IV, Part One goes out of his way to say that when younger he 'could have crept into any Alderman's thumb-ring'. This is followed by a passage in which he says to Hal: 'Thou art my son.'

Chapter Fourteen How Shakespeare's mother played with him

Some say that the first word spoken by William Shakespeare was neither 'Cheese!' nor ' Roses! ' but that as soon as he came forth from his mother's womb he cried out with a great voice and what he cried was this: 'Drink! Drink! I want drink! Bring me ale to drink!'

No doubt you do not believe the truth of this first saying of Shakespeare's after his nativity. No more do I. But tell me, if it had been the will of God that the babe should cry out not as other babes do but in this wise, would you still say that little Willy could not have done so? I tell you, it is not impossible with God that a child should speak in the first moment of his life, and that he might call out for a pot of ale, if he wanted one.

Be that as if may, the midwife Gertrude told me on her oath that at the sound of his father's flagons clinking the baby William would of a sudden fall into an ecstasy, as if he had then tasted of the joys of paradise. So that every morning his mother would strike with a spoon upon a glass or a bottle, and at the sound her son would become happy, lolling and rocking himself in his cradle, nodding with his head, a perfect little tosspot.

And if he happened to be vexed, or if he did fret, or weep, or cry, they had only to bring him some ale in a bottle with a teat, and he would be instantly pacified, and as still and as quiet as they could wish.

WS was by all accounts a fine, handsome boy, and of a burly physiognomy. In fact he cried little, and laughed when he could. He beshat himself very smartly every hour. To speak truly of him, as Dr Rabelais says of the infant Gargantua, he was wonderfully phlegmatic in his posteriors. So what did Shakespeare do in the days of his beginning? He did, sir, what you did, and what I did, and what even you did, madam. That is to say, he passed the time like any other child since the birth of the world. He passed his time in drinking and in eating and in sleeping. And he passed his time in eating and in sleeping and in drinking. And he passed his time in sleeping and in drinking and in eating. And he passed his time in eating and in drinking and in sleeping. And he passed his time in sleeping and in eating and in drinking. And he passed his time in drinking and in sleeping and in eating.

And, sometimes, as I say, he shat himself.

And as soon as he learnt to walk he learnt to run. He may even have learnt to run before he could walk. Before or after, in no time at all the boy Shakespeare was chasing after butterflies. And in no time at all he had trod his shoes down at the heel.

What were his very first games?

He blew bubbles at the sun through a yarrow straw. He shooed his mother's geese, sir, and he pissed in his breeches and his bed.

What were his very first fancies?

He hid himself in the river for fear of rain. He hoped to catch larks, madam, if ever the blue skies should fall.

What else did he do?

He shat in his shirt. He wiped his nose on his sleeve. He let his snivel run down into his porridge, and then gobbled up the brew. He slobbered and he dabbled in the ditch. He waddled and he paddled in the mire. He sang sweet songs and he combed his hair with a bowl of chicken gruel.

What else did he think?

Why, he thought that the moon was made of green cheese, and that if he ate cabbage he would shit beets, and that if he beat the bushes he might catch the throstle-cocks.

So what was his first ambition?

To run away.

Is it true that Shakespeare was a lecher, even as a child?

It is true, so they say, that little WS was always groping his nurses and his governesses, upside down, arsiversy, topsiturvy, handling them very rudely under their petticoats in all the jumbling and the tumbling he could get into.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «The Late Mr Shakespeare»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «The Late Mr Shakespeare» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «The Late Mr Shakespeare» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.