Upton Sinclair - Love's pilgrimage

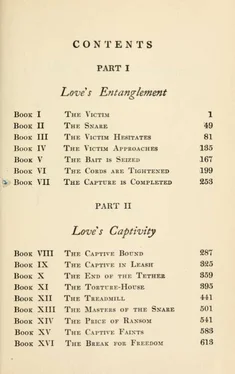

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Upton Sinclair - Love's pilgrimage» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 1911, Издательство: New York : M. Kennerley, Жанр: Старинная литература, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Love's pilgrimage

- Автор:

- Издательство:New York : M. Kennerley

- Жанр:

- Год:1911

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:4 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Love's pilgrimage: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Love's pilgrimage»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

Love's pilgrimage — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Love's pilgrimage», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

It was not merely that he never touched stimulants; he had an instinct against all things that were softening and enervating, all things that tempted and enslaved. For him was the morning-air, and the shock of cold water, and the hardness of the wild things of the open. Other people did not feel this way; other people pampered themselves and defiled themselves-— and so Thyrsis went apart. He lived quite alone with his thoughts, he had never a chum, scarcely even any friends. Where in the long procession of lodging and boarding-houses and summer-resorts should he meet people who knew what he knew about life? Where in all the world should he meet them, save in the books of great men in times past?

There was not much of what is called "culture" in his family; no music at all, and no poetry. But there were novels, and there were libraries where one could get more of these, so Thyrsis became a devourer of stories; he would disappear, and they would find him at meal-times, hidden in a clump of bushes, or in a corner behind a sofa—anywhere out of the world. He read whole libraries of adventure: Mayne-Reid and Henty, and then Cooper and Stevenson and Scott. And then came more serious novels—"Don Quixote" and "Les Miserables," George Eliot, whom he loved, and Dickens, whose social protest thrilled him; and chiefest of all Thackeray, who moulded his thought. Thackeray Vnew the world that he knew, Thackeray saw to the

LOVE'S PILGRIMAGE

heart of it; and no high-souled lad who had read him and worshipped him was ever after to be lured by the glamor of the "great" world —a world whose greatness was based upon selfishness and greed.

Thyrsis knew no foreign language, and fate or instinct kept him from those writers who jested with un-cleanness; so he was virginal, and pure in all his imaginings. Other lads exchanged confidences in forbidden things, they broke down the barriers and tore away the veils; but Thyrsis had never breathed a word about matters of sex to any living creature. He pondered and guessed, but no one knew his thoughts; and this was a crucial thing, the secret of much of his aloofness.

§ 4. IN one of the early boarding-houses there had been a little girl, and the families had become intimate. But the two children disliked each other, and kept apart all they could. Thyrsis was domineering and imperious, and things must always be his way. He was given to rebellion, whereas Corydon was gentle and meek, and submitted to confinements and prohibitions in a quite disgraceful manner. She was a pretty little girl, with great black eyes; and because she was silent and shy, he set her down as "stupid", and went his way.

They spent a summer in the country together, where Thyrsis possessed himself of a sling-shot, and took to collecting the skins of squirrels and chipmunks. Corydon was horrified at this; and by way of helping her to overcome her squeamishness he would make her carry home the bleeding corpses. He took to raising, young birds, also, and soon had quite an aviary—two robins, and a crow, and a survivor from a brood of "cherry-birds." The feeding of these nestlings was no small

task, but Thyrsis went fishing when the spirit moved him, secure in the certainty that the calls of the hungry creatures would keep Corydon at home.

This was the way of it, until Corydon began to blossom into a young lady, beautiful and tenderly-fashioned. Thyrsis still saw her now and then, and he made attempts to share his higher joys with her. He had become a lover of poetry; once they walked by the seashore, and he read her "Alexander's Feast", thrilling with delight in its resounding phrases:

"Break his bands of sleep asunder, And rouse him like a rattling peal of thunder!"

But Corydon had never heard of Timotheus, and she had not been taught to exploit her emotions. She could only say that she did not understand it very well.

And then, on another occasion, Thyrsis endeavored to tell her about Berkeley, whom he had been reading. But Corydon did not take to the sensational philosophy either; she would come back again and again to the evasion of old Dr. Johnson—"When I kick a stone, I know the stone is there!"

This girl was like a beautiful flower, Thyrsis told himself—like all the flowers that had gone before her, and all those that would come after, from generation to generation. She fitted so perfectly into her environment, she grew so calmly and serenely; she wore pretty dresses, and helped to serve tea, and was graceful and sweet—and with never an idea that there was anything in life beyond these things. So Thyrsis pondered as he went his way, complacent over his own perspicacity; and got not even a whiff of smoke from the volcano of

rebellion and misery that was seething deep down in her soul!

The choosers of the unborn souls had played a strange fantasy here; they had stolen one of the daughters of ancient Greece, and set her down in this metropolis of commercialdom. For Corydon might have been Nau-sikaa herself; she might have marched in the Pan-athenaic procession, with one of the sacred vessels in her hands; she might have run in the Attic games, bare-limbed and fearless. Hers was a soul that leaped to the call of joy, that thrilled at the faintest touch of beauty. Above all else, she was born for music—she could have sung so that the world would have remembered it. And she was pent in a dingy boarding-house, with no point of contact with anything about her—with no human soul to w r hom she could whisper her despair!

They sent her to a public-school, where the sad-eyed drudges of the traders came to be drilled for their tasks. They harrowed her with arithmetic and grammar, which she abhorred; they taught her patriotic songs, about a country to which she did not belong. And also, they sent her to Sunday-school, which was worse yet. She had the strangest, instinctive hatred of their religion, with all that it stood for. The sight of a clergyman with his vestments and his benedictions would make her fairly bristle with hostility. They talked to her about her sins, and she did not know what they meant; they pried into the state of her soul, and she shrunk from them as if they had been hairy spiders. Here, too, they taught her to sing—droning hymns that were a mockery of all the joys of life.

So Corydon devoured her own heart in secret; and in time a dreadful thing came to happen—the stagnant soul beginning to fester. One day the girl, whose heart

was the quintessence of all innocence, happened to see a low word scribbled upon a fence. And now—they had urged her to discover sins, and she discovered them. Suppose that word were to stay in her mind and haunt her— suppose that she were not able to forget it, try as she would! And of course she tried; and the more she tried, the less she succeeded; and so came the discovery that she was a lost soul and a creature of depravity! The thought occurred to her, that she might go on to think of other words, and to think of images and actions as well; she might be unable to forget any of them—her mind might become a storehouse of such horrors! And so the maiden out of ttz^ient Greece would lie awake all night and wrestle with fiends, u^til she was bathed in a perspiration.

§ 5. ABOUT this time Thyrsis was making his debut as an author. He had discovered a curious knack in himself, a turn for making verses of a sort which were pleasing to children. They came from some little corner of his consciousness, he scarcely knew how; but there was a paper that was willing to buy them, and to pay him the princely sum of five dollars a week! This would pay for his food and his hall bedroom, or for board at some farm in the summer; and so for several years Thyrsis was free.

He told a falsehood about his age, and entered college, and buried himself up to the eyes in work. This was a college in a city, and a poor college, where the students all lived at home, and had nothing to do but study ; and so Thyrsis missed all that beneficent illumination known as "student-life." He never hurrahed at foot-ball contests, nor did he dress himself in honorific garments, nor stupify himself at "smokers." Being

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Love's pilgrimage»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Love's pilgrimage» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Love's pilgrimage» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.